INTRODUCTION

Frontal bone fractures account for 5% to 15% of all facial fractures, with motorcycle accidents being the most common mechanism of injury [1,2,3]. Frontal fractures are grouped into three distinct general categories: anterior table fractures, posterior table fractures, and combined fractures [3,4]. Among these, isolated anterior table fractures account for 33% to 39% of frontal sinus fractures [5]. Many agree on the general principles of frontal fracture management as described below, but the methods of reduction are still controversial [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. In cases of nondisplaced anterior or posterior wall fractures, seven days of antibiotic treatment without surgical intervention is recommended. Follow-up computed tomography (CT) should be performed to confirm any complications or sequelae. During follow-up, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage may persist due to a posterior wall fracture, which necessitates craniotomy or dural repair. Displaced posterior wall fractures require reduction of the fracture with additional treatment. In cases of concomitant CSF leakage or frontonasal duct injury, reduction and fixation of the fracture with dural repair and obliteration of the sinus and the frontonasal duct should be performed, and cranialization may be considered. Such complicated procedures are best performed through a coronal incision [8,9]. If there is only a displaced anterior table fracture with an intact frontonasal duct, reduction with or without fixation is the treatment of choice. Because an isolated anterior table fracture is the most common fracture type, extensive clinical experience determines the ideal method for approaching the anterior table [10,11,12,13,14]. However, the management of frontal sinus fractures remains somewhat controversial, because finding a balance between an acceptable cosmetic outcome with a minimum scar and rigid fixation via sufficient exposure is not easy.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

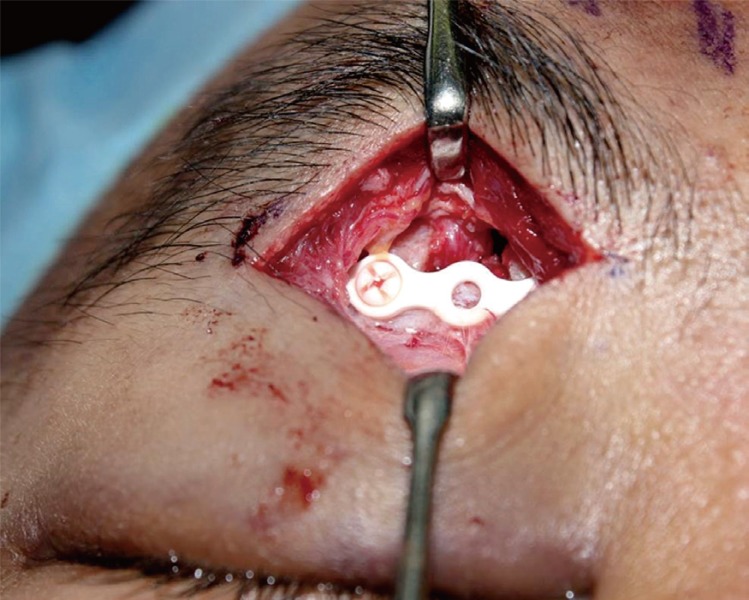

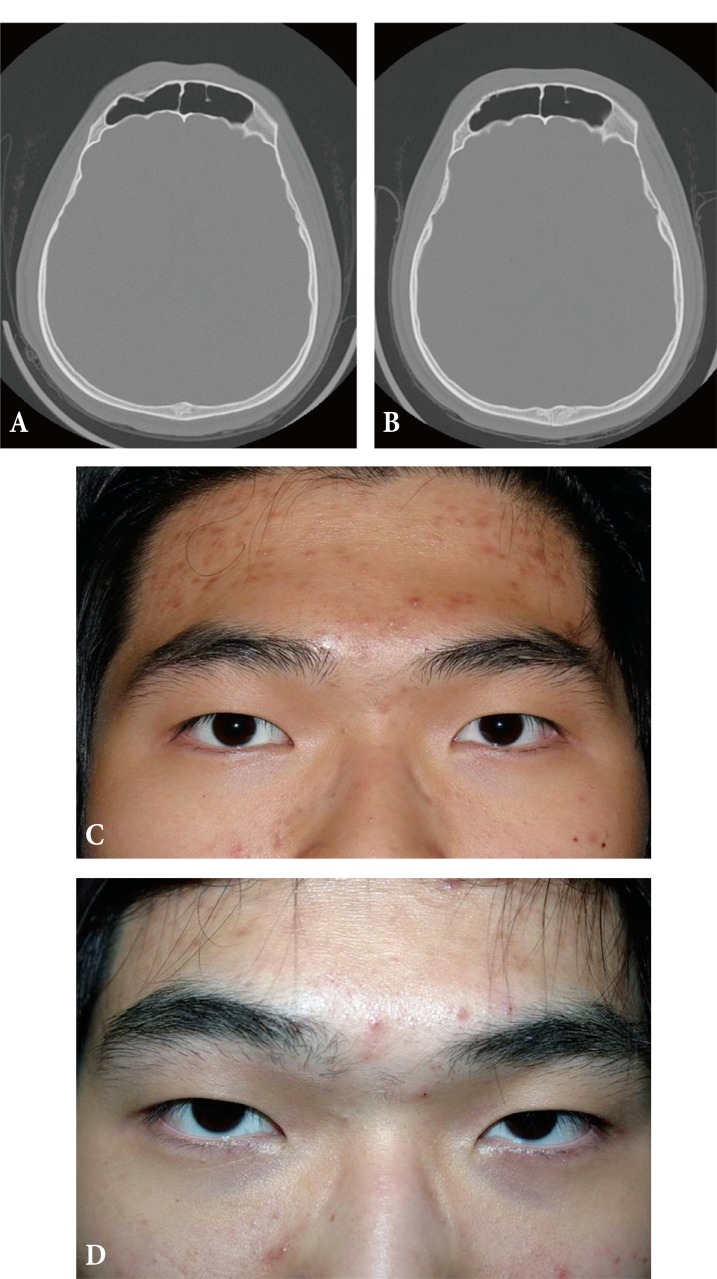

Under general anesthesia, the incision line will follow the lower edge of the eyebrow, from slightly medial to the medial limbus axis line to approximately 1.0 cm medial to the tail of the brow. In order to obtain an inconspicuous scar, keeping this upper incision precisely at the lower margin of the brow is very important. Dissection is performed between the loose areolar tissue and periosteum by using an elevator. The superior orbital rim is exposed by gently dissecting the orbital septum and the orbicularis oculi muscle. A periosteal incision is made 3 mm from the superior orbital rim. Meticulous dissection is performed around previously marked areas for the identification and preservation of the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves and vessels (Fig. 1). After exposure of the fracture site in the frontal bone, reduction is performed using a periosteal elevator and bone hook. After reduction of the fractured segment is accomplished, bone fixation is performed using a plate and screws (Fig. 2). When fractures are located in the center of the forehead, screw fixation through the incision is very difficult. In these cases, a plate is placed at the fracture site through the subbrow incision and an additional 5–7-mm midline glabella incision is made only for screw fixation. This can be a pitfall of this approach.

ANOTHER APPROACH

A bicoronal approach has been considered the standard approach in craniofacial surgery for many years. Patients who require obliteration or cranialization procedures require a bicoronal incision. Although a bicoronal incision offers adequate exposure, it requires a longer operative time and hospital stay. It has severe disadvantages, including a long scalp scar, alopecia, and temporal hollowing caused by extensive dissection [4,5,10,11,15]. The main problem with an isolated anterior wall fracture is the aesthetic deformity of the forehead, which seldom causes functional complications; therefore, if the surgical approach leaves more severe deformities, as described above, it should not be considered the treatment of choice. Many patients may prefer a slight depression of the forehead rather than the long visible scar caused by a coronal incision. Open reduction of a frontal sinus fracture via a bicoronal incision has drawbacks for patients with simple depressed forehead fractures. Thus, in recent years, minimally invasive approaches to anterior table fractures have been used.

The endoscopic approach was first described by Graham and Spring [16] in 1996. The major bone fragments of an anterior table fracture with an intact posterior sinus wall were elevated without internal fixation. They reported that the patient had complete restoration of the cosmetic defect without postoperative complications. In 2003, Strong et al. [5] attempted endoscopic reduction and fixation in a cadaver study. They concluded that the degree of comminution dictated the success of the repair. When there were significant comminutions or marked fractures, rigid fixation could not be performed in a noninvasive manner. The endoscopic approach also has disadvantages, including a steep learning curve, narrow field of view, and lack of depth perception [9,15].

Kim et al. [12] treated patients with anterior table frontal sinus fractures using a transcutaneous, transfrontal approach through a small peri-eyebrow skin incision. However, rigid internal fixation is not possible if the skin incision is not extended to the fracture site; in cases of a severely comminuted fracture, adequate reduction cannot be achieved, since the transfer of a strong reduction force only by the insertion of a miniature periosteal elevator through the incision site is nearly impossible.

Yoo et al. [13] performed a successful transcutaneous reduction of a frontal sinus fracture by using a bone tapper device with a 3-mm slit incision. This method involving the use of a tapper was considered easy to perform, with relatively sufficient strength for handling a bony segment as compared to the use of elevators. A 3-mm slit incision did not cause any problematic scars, but it was not adequate for the internal fixation of fractured segments.

Noury et al. [14], treated anterior table frontal sinus fractures using frontal rhytid forehead incisions, and concluded that this approach offered a good cosmetic result, with the ability to perform internal fixation. However, their method is inappropriate for use in young patients with an invisible frontalis rhytid. In addition, there is still a risk of a long apparent scar across the forehead and paresthesia above the incision from an injury of the supratrochlear or supraorbital nerve.

Montovani et al. [17] treated patients with frontal sinus fractures by making a butterfly incision below the eyebrows, which provided adequate exposure not only for internal fixation but also for more complicated procedures such as obliteration and cranialization. It is difficult to hide a scar on the nasal dorsum, which connects the bilateral infrabrow incisions, and there is no need for bilateral infrabrow incisions in the case of a unilateral frontal sinus fracture. A butterfly incision may be considered too extensive for the treatment of an isolated anterior table fracture [3,6,7].

ADVANTAGES

The transcutaneous approach through a subbrow incision offers many advantages. An almost direct visualization of the fracture enables an accurate reduction of the anterior table of the frontal sinus. Rigid internal fixation, which was not possible by endoscopic and other minimal transcutaneous approaches, was performed in all cases. Minimization of the scar was achieved by camouflaging the scar at the lower margin of the eyebrow. This incision line is widely used in aesthetic blepharoplasty procedures and leaves an acceptable scar [18,19]. A subbrow incision is considered superior to the frontalis rhytid, butterfly, or some cases of bicoronal incisions because of the inconspicuous scar (Fig. 3).

COMPLICATIONS

The main limitation of the transcutaneous approach through a subbrow incision is that rigid internal fixation cannot be performed when the fracture is in the medial frontal sinus. Although the extent of periosteal dissection through the subbrow incision is from the origin of the temporalis muscle to beyond the midline of the forehead, internal fixation is not easy to perform when the fracture is placed around the midline. In such cases, a 5–7-mm slit incision for screw fixation is used to achieve rigid internal fixation. Numbness due to traction injury to the nerves during reduction and fixation is theoretically possible. However, in our experience, complete identification and minimal handling of the nerves are possible because the subbrow incision provides a sufficient visual field. Therefore, we have not encountered cases with traction injury of the supratrochlear or supraorbital nerves. However, numbness can be a major complication.