|

|

- Search

| Arch Craniofac Surg > Volume 15(3); 2014 > Article |

Abstract

Reconstruction of a full-thickness alar defect requires independent blood supplies to the inner and outer surfaces. Because of this, secondary operations are commonly needed for the division of skin flap from its origin. Here, we report a single-stage reconstruction of full-thickness alar defect, which was made possible by the use of a nasolabial island flap and septal mucosal hinge flap. A 49-year-old female had presented with a squamous cell carcinoma of the right ala which was invading through the mucosa. The lesion was excised with a 5-mm free margin through the full-thickness of ala. The lining and cartilage was restored using a septal mucosa hinge flap and a conchal cartilage from the ipsilateral ear. The superficial surface was covered with a nasolabial island flap based on a perforator from the angular artery. The three separate tissue layers were reconstructed as a single subunit, and no secondary operations were necessary. Single-stage reconstruction of the alar subunit was made possible by the use of a nasolabial island flap and septal mucosal hinge flap. Further studies are needed to compare long-term outcomes following single-stage and multi-stage reconstructions.

The overall goal of alar reconstruction is to restore the flared external appearance of lateral elements. As it is for the rest of the nose, the alar subunit is a composite tissue with complex three-dimensional morphology. Each layer of the ala has a set of distinctive biomechanical properties that contribute to the overall architecture of a supple but patent airway inlet.

Small, superficial defects of the ala can be reconstructed using full-thickness skin grafts and random flaps, with the blood supply for the rest of the subunit supplied by the mucosal vasculature. The main reconstructive challenge behind larger and deeper defects stems from the absence of an intact and separate vascular supply; the reconstructed mucosal lining and skin flap must each have an independent blood supply. Both nasolabial and forehead flaps provide an adequate blood supply to sustain the flaps themselves and for the interposed cartilage graft. However such flaps are bulky and require a delayed operation for the pedicle division.

In this case report, we present a case of full-thickness alar defect, which was reconstructed in a single stage using a combination of a septal hinge flap, conchal cartilage graft, and a nasolabial island flap. We found that compared with a forehead flap, this flap provides both an adequate length for patients with a short forehead flap length, and allows the operation to be performed as a single-stage procedure. This single-stage modification using nasolabial fold flap obviates the need for additional surgery and permits a full-thickness reconstruction to be conducted at the same time. Although such modifications had been described for reconstructions based on forehead flaps, this is the first detailed report on a single-stage reconstruction using the nasolabial fold flap. We expect that this technique will be particularly helpful for patients who require a forehead flap but have a short forehead length yet still wish for a single-stage reconstruction for nasal defects.

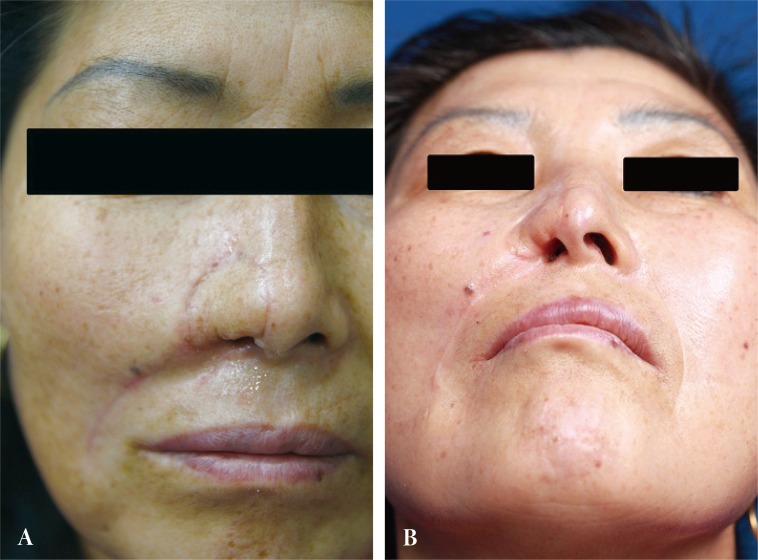

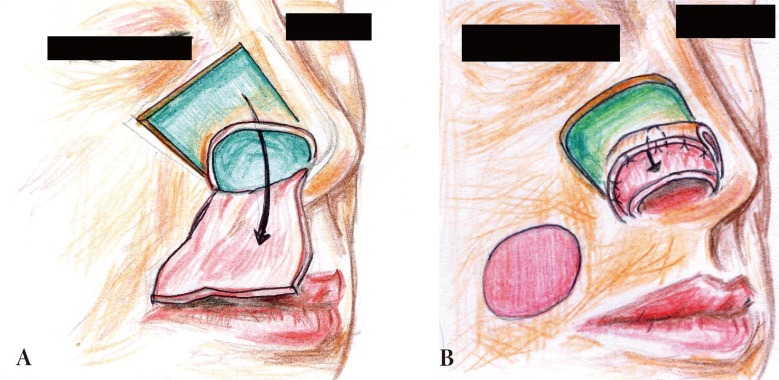

A 46-year-old female was referred from an outside hospital for squamous cell carcinoma of the right ala. The mass measured 2 × 1.5 cm and had an ulcerated portion from a previous punch biopsy site (Fig. 1). A single-stage operation was offered, to which the patient consented. The tumor was excised through all three layers with a 5 mm margin, and the resultant defect measured 2.5 × 2.0 cm. Intraoperative frozen biopsy report was consistent with squamous cell carcinoma. The lining mucosal defect measured 2.0 × 1.5 cm, and the graft for this inner layer was prepared using a septal mucosal hinge flap based on the septal branch of the superior labial artery. The typical incisional boundaries of a mucosal flap are located superiorly, about 1 cm from the nasal dorsum, inferiorly along the maxillary crest, and posteriorly as far as the extent of the defect. The mucosal flap was elevated from the septum in a posterior-to-anterior direction and turned laterally toward the defect, such that the mucoperichondrium was external and the mucosa faced internally (Fig. 2) [1]. A right conchal cartilage graft was harvested, fashioned into a suitable shape, and placed over the mucosal hinge flap to provide structural support. The outermost surface was restored using a nasolabial island flap with a subcutaneous pedicle that was based on a perforator vessel from the angular artery. This flap was designed using a 3 × 2 cm mirror-image template from the contralateral ala, and was elevated in an inferior-to-superior direction. Once rotated over the septal mucosa-conchal graft construct, the flap was sutured into place (Fig. 3). The nasolabial fold was re-established with primary closure of the cheek skin, under which a capillary drain was left for three days and then removed.

The postoperative course was uneventful, without any vascular complications. By 6 months, however, scar contraction along the reconstructed rim had resulted in a partially obstructed inlet with mild asymmetry. A nostril implant was used to improve the patency. At 8 months, the patient was satisfied with the operative outcomes. No subsequent interventions were necessary (Fig. 4).

The nose is a highly sophisticated structure with multiple tissue layers and interposed curvatures and convexities. For a systemic approach of the reconstruction of various nasal defects, Burget and Menick [2] divided this central facial feature into six units, consisting of the dorsum, tip, soft triangle, columella, alar, and sidewall. Since then, nasal reconstructions have followed the idea that a defect is best resurfaced as a unit not as a plug in a hole. The goal of reconstruction after tumor excision is minimum deformity of the nose and donor site. To achieve this, the color and texture of the area must be considered. These challenges for aesthetic and functional reconstruction have been met by the development of various techniques such as skin grafts, local flaps, and the V-Y bipedicle flap.

Small superficial defects can be allowed to heal by secondary intention, or they can be resurfaced with a skin graft or a local flap. Generally, skin grafts are not technically demanding and avoid the problem of contracture-related deformities that result from primary closures. However, they are vulnerable to injury. Matching flap thickness, texture, and color present challenges. Delayed scar contracture is another problem that may occur for several years after reconstruction [3,4,5,6,7].

In the case presented, the nasal mucosal defect was reconstructed by a full-thickness mucosal graft. We chose the mucosal flap over skin grafts, which lack mucous secretion and are associated with crusting and malodor [8].

The forehead flap is the workhorse of nasal reconstruction. This robust flap has a texture and color that matches the nasal skin fairly well, and can be used to reconstruct all subunits of the nose. However, its pedicle is buried within the frontalis muscle, which must be trimmed during the second operation and divided in a third operation. While there is no better substitute for larger nasal defects, the forehead flap unnecessarily subjects patients to repeat operations and leaves them with a significant forehead scar. Additionally, the anecdotal experience has been that this flap is inadequate in reaching the lower nasal subunits of Korean patients [9].

With advanced understanding of perforator anatomy, single-stage reconstructions using forehead island flaps have been reported in case reports. These tunneled island flaps have been used for single-stage reconstructions of the dorsal subunits of the nose. We have yet to find a report of a forehead island flap being used to reconstruct the alar subunit in isolation, and suspect that most surgeons would find such a reconstructive strategy to be convoluted and risky.

In the reconstruction of large alar surface defects, the closest axial flap with a definite blood supply is the nasolabial flap. Considering its color, texture, and the resulting donor site scar, the nasolabial skin is the proper donor site for nasal ala reconstruction. The only drawback of the flap is that it requires two stages to resurface a normal-looking ala, even when an island subcutaneous pedicle flap is used [10]. The arc of rotation and mobility of the flap are not sufficient to allow single-stage reconstruction. The perforator-based nasolabial flap, however, provides a one-stage procedure and free style design of the flap shape, due to its arc of rotation. The nasolabial flap based on lateral nasal artery requires the division of the levator labii superioris and zygomaticus minor muscle [11]. This is an unnecessary morbidity to the patient because the perforator based version of the nasolabial flap can be rotated towards the nose freely, as was demonstrated in our case.

Prior to this report, full-thickness ala reconstruction using a perforator-based nasolabial flap with the combination of a septal mucosal hinge flap and auricular cartilage graft has not been discussed in detail. Among the spectrum of reconstructive options for ala defects, we prefer the perforator-based nasolabial flap because it allows the reconstruction of full-thickness nasal alar skin defect and has a wider arc of rotation, and therefore it enables us to perform a single-stage procedure. In our case, we had first considered and even designed the forehead flap in the patient, but our final preference was to use the nasolabial flap described. The nasolabial flap design provided adequate length of soft tissue, whereas the forehead flap might not have reached the lower portion of the nose. A cartilage graft is essential for safe and reliable reconstruction. A chondrocutaneous composite graft was used to reconstruct the three-dimensional components of the ala subunit. Also, the single-stage approach decreases overall cost of care and shortens the recovery time.

The most undesirable outcome from this technique was the nostril contracture in the healing phase. Application of nostril implant supporting the alar rim can prevent the ala from constricting inward, contracting upward, and/or collapsing. Another drawback of this flap was the longer operation time.

These days, a growing number of patients are diagnosed with skin cancer. The nose is especially vulnerable to skin cancer from additional exposure to ultraviolet rays. Nasal skin malignancies are usually present in elderly patients, among whom the medial cheek skin is redundant above the nasolabial fold. This is another reason we prefer the single-staged nasolabial fold flap to reconstruct full-thickness skin defects after tumor excision.

In this case, the reconstructive goals were to re-produce a nose that was as close to a normal appearance as possible. We were able to achieve satisfactory aesthetic outcomes without the need for additional operations and without any severe structural complications.

Ours is a case report of alar reconstruction using a nasolabial flap and septal mucosal hinge flap in a patient with a relatively short forehead length. Although use of nasolabial fold in alar reconstruction has been has presented elsewhere, this is first such case to be reported from within Korea. Considering the number of patients among whom forehead flaps might be inadequate, we consider this single-stage reconstruction to be indicated in the reconstruction of lower nasal defect among Korean patients. In summary, we present in detail a modified single-stage method of ala reconstruction using a nasolabial and septal mucosal hinge flap. The method is especially useful in patients among whom short foreheads do not provide flaps of adequate length for lower portions of the nose.

References

1. Driscoll BP, Baker SR. Reconstruction of nasal alar defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2001;3:91-99. PMID: 11368658.

2. Burget GC, Menick FJ. The subunit principle in nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1985;76:239-247. PMID: 4023097.

3. Kazanjian VH, Converse JM. Kazanjian & Converse's surgical treatment of facial injuries. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1974.

4. Grabb WC, Smith JW, Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne C. Grabb and Smith's plastic surgery. Boston: Lippicott-Raven; 1979.

5. Converse JM. Reconstructive plastic surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co.; 1977.

6. Barron JN, Saad MN. Operative plastic and reconstructive surgery. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1980.

7. Farrior RT. Corrective and reconstructive surgery of the external nose. In: Naumann HH, editors. Head and neck surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Sauders Co.; 1980. p. 256-257.

8. Letterman G, Schurter M. The split-thickness skin graft in the management of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia involving the nasal mucosa. Plast Reconstr Surg 1964;34:126-135. PMID: 14198555.

9. Gardetto A, Erdinger K, Papp C. The zygomatic flap: a further possibility in reconstructing soft-tissue defects of the nose and upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;113:485-490. PMID: 14758207.

10. D'Arpa S, Cordova A, Pirrello R, Moschella F. Free style facial artery perforator flap for one stage reconstruction of the nasal ala. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2009;62:36-42. PMID: 18945660.

11. Turan A, Kul Z, Turkaslan T, Ozyigit T, Ozsoy Z. Reconstruction of lower half defects of the nose with the lateral nasal artery pedicle nasolabial island flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119:1767-1772. PMID: 17440352.

Fig. 2

(A) A flap based on the caudal septum was reflected laterally. (B) The inner lining was reconstructed using an ipsilateral septal mucosal hinge flap. The ear cartilage was placed on the raw surface.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 2 Crossref

- Scopus

- 6,960 View

- 113 Download

- Related articles in ACFS

-

Reconstruction of Cheek Defect with Facial Artery Perforator Flap.2012 October;13(2)

Reconstruction of Craniofacial Bone Defect with Titanium Dynamic Mesh.2000 October;1(1)