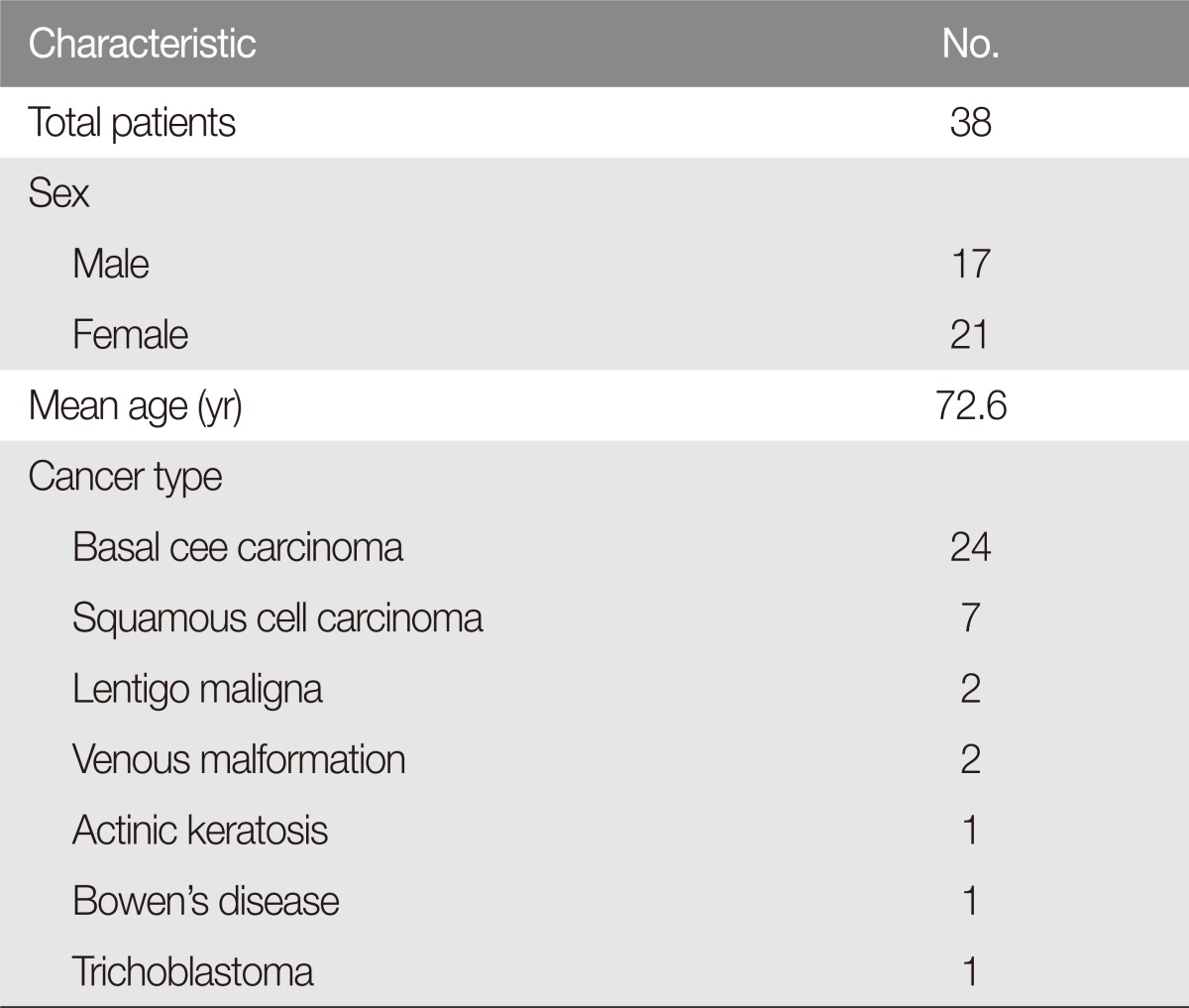

|

|

- Search

| Arch Craniofac Surg > Volume 17(4); 2016 > Article |

Abstract

Background

The cheek rotation flap has sufficient blood flow and large flap size and it is also flexible and easy to manipulate. It has been used for reconstruction of defects on cheek, lower eyelid, or medial and lateral canthus. For the large defects on central nose, paramedian forehead flap has been used, but patients were reluctant despite the remaining same skin tone on damaged area because of remaining scars on forehead. However, the cheek flap is cosmetically superior as it uses the adjacent large flap. Thus, the study aims to demonstrate its versatility with clinical practices.

Methods

This is retrospective case study on 38 patients who removed facial masses and reconstructed by the cheek rotation flap from 2008 to 2015. It consists of defects on cheek (16), lower eyelid (12), nose (3), medial canthus (3), lateral canthus (2), and preauricle (2). Buccal mucosa was used for the reconstruction of eyelid conjunctiva, and skin graft was processed for nasal mucosa reconstruction.

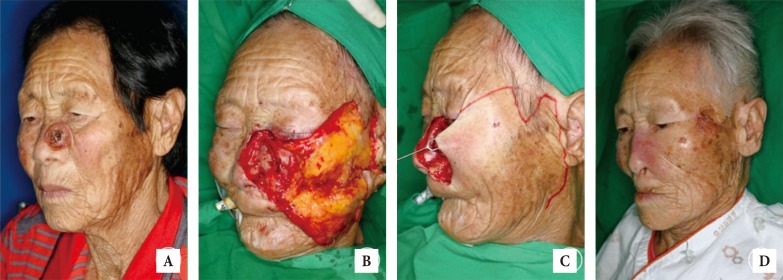

Results

The average defect size was 6.4 cm2, and the average flap size was 47.3 cm2. Every flap recovered without complications such as abnormal slant, entropion or ectropion in lower eyelid, but revision surgery required in three cases of nasal side wall reconstruction due to the occurrence of dog ear on nasolabial sulcus.

The plastic surgeon should consider the location, size, depth, and the adjacent tissue relax degree when reconstructing the defect site after removal of the facial tumor. The cheek rotation advancement flap is one of the local flaps that reconstructs the face and is used to reconstruct the cheeks or the wide lower eyelid defect. It is also used for reconstruction of medial or lateral canthal defects because of its flexibility and easily manipulated treats [1]. Reconstruction of the medial and lateral canthal defects is challenging for the operator because it is complex structure consisting tendon, conjunctiva, tarsus, and upper or lower eyelid skin.

Existing local flaps such as bilobed flap, glabella V-Y advancement flap, and limberg flap can be considered for reconstruction of small nasal defects, but they are not applicable for the large defects. The paramedian forehead flap is usually used for reconstruction of the medial and lateral canthal, or nasal defects, but there is a disadvantage that the scar of the donor site remains on the forehead of the patient, which makes the patient reluctant.

The cheek rotation flap can cover a large area and has a sufficient blood supply and definite vascular supply area. The flap is flexible, well-deflected and easy to manipulate, and has a pivot point that can be freely changed as the pedicle of the flap is placed anteriorly or posteriorly (Fig. 1).

Therefore, we aimed to demonstrate that using the cheek flap is reliable and effective to construct the large nasal defects as well as medial and lateral canthal defects.

This study is retrospective case study on patients who received the cheek rotation flap after surgical remove of facial mass from January 2008 to December 2015. A total of 38 patients underwent surgery, 17 in males and 21 in females. The subject age ranged from 46 to 88 years old, and the mean was 72.6 years old (Table 1). All procedures were performed under general anesthesia in the same manner by one surgeon. There were 24 cases of basal cell carcinoma, 7 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, 2 cases of malignant black spot, and 2 cases of vein malformation. The location of the defect was classified into 16 cases in the cheek, 12 cases in the lower eyelid, 3 cases in the nose, 3 cases in the medialcanthus, 2 cases in the lateral canthus, and 2 cases in the preauricle.

The extent of resection of skin tumors was determined based on preoperative diagnosis. Frozen section biopsy was performed at the edge of the removed tissue, confirming that no tumor cells remained at the tissue interface. The incision line ran transversely from the defect to the preauricular crease, earlobe, and occipital hairline inferiorly (Fig. 1). When the incision line of the flap extended to the inferior earlobe and anterior occipital hairline, a larger flap could be elevated. The flap was elevated above the submuscular aponeurotic system (SMAS) and reconstructed the defect area by advancing while keeping subdermal plexus. The donor portion of the flap was closed with primary suture or skin graft (closure). Five to seven Penrose drain tubes were placed to prevent hematomas under the flap, and mild compressive dressing was done. Medical leeches were used to treat venous congestion above the cheek flap.

The medial canthal skin tumor was removed together withtendon, lacrimal point, lacrimal duct, conjunctiva and lower eyelid skin, and periosteum was also removed. In order to reconstruct this, an entire layer of tissue remaining intact was constructed to be included at the distal end of the cheek rotation flap, and the flap was elevated from the superior periosteum to the inside to reconstruct the medial canthus (Fig. 2).

The medial canthoplasty was performed by fixingtarsus included in the flap to the medial canthuswith 5-0 nylon. The medial canthal lower eyelid was reconstructed in a full thickness, which resulted in a tightness of the lower eyelid effectively, which vector towards superior medial direction. To reconstruct the conjunctiva between the eye and the remainder of the cheek flap, the buccal mucosa was implanted on the raw surface of the flap to be the outer lower eyelid.

The lateral canthal skin tumors were removed together with lateral canthal tendon of outer eyelid, conjunctiva, skin, and the periosteum was removed. To reconstruct not only the lower eyelid but also the upper eyelid, the cheek flap design was constructed with a high arch to the eyebrow level (Fig. 3). In order to perform lateral canthoplasty, a hole was drilled on the lateral orbital bone, and the lateral canthal subjacent subcutaneous tissue of the cheek flap was placed on the cheek flap using nylon 5-0. The ectropion in lower eyelid was avoided by the use of a button-operated traction suture. The lateral commissure of the eyelid was reconstructed by splitting the flap in parallel, and the conjunctiva was reconstructed by implanting the buccal mucosa under the flap.

Malignant skin tumors of the nasal sidewall were removed along with the upper and lower lateral cartilage and nasal mucosa. The margins of the periosteum and nostril bone (margin of the pyriform sinus) were removed using a burr and a rongeur, and the defect areawas very large (Fig. 4).

The nasal mucosa was reconstructed by turning over the skin taken through split thickness of the upper arm and fixing to the remaining nasal mucosa with 6-0 paingut. Cheek flap was largely constructed to cover a large defect site, and the dead space between the transplanted skin and the cheek flap was reduced using the bed site suture. Petrolatum gauze was also gently filled into inside of nose so that the transplanted skin could attach to the bottom of the flap.

The average defect size was 6.4 cm2, the average size of the cheek flap was 47.3 cm2, and the largest flap size was 62.5 cm2 (Table 2). The donor site of the flap was done primary closure in 28 patients (73.7%) and covered with skin graft in 10 patients (26.3%). No abnormal slant, entropion or ectropion of the lower eyelid occurred in the reconstruction of the eye margin. However, in three cases of reconstructing the large nasal sidewall defect, the flap was over-elevated and the rotation-advancement to the nasal sidewall resulted in dog ear in the ipsilateral side of nasolabial sulcus. This dog ear could not be removed from the first operation because it serves as the base of the flap and provides a sufficient vascularity. However, after about one month, the patient underwent simple revision surgery under local anesthesia completely removing the dog-ear and attained smooth nasolabial sulcus (Fig. 5). Venous congestion was observed on the edge of the flap in two cases, but the flap was well healed without necrosis after leech therapy. There were no postoperative complications such as infection, hematoma, and seroma. The average length of hospital stay was 5 days. The mean time from onset to operation was 67.5 months and the mean follow-up period was 18 months. Patients and caregivers were satisfied with the surgical outcome.

Skin tumors have been reported to occur in older age groups. Recently, skin cancer patients are increasing in the elderly population with increasing life expectancy [2]. The most common skin tumors in the face are basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by the skin that is exposed to sunlight, especially 80% of the face. The rate of occurrence in the nose and eyes around the face is known as 30% and 14% [3,4].

Nose and eye in the face are important factors that determine the impression. Reconstruction of these defect sites using primary sutures or skin grafts is not a desirable method because it causes problems of twisting, deforming, and contracting the surrounding tissue. Therefore, structural damage concomitant with the defects exposing bone, cartilage and otherscan be reconstructed as close to original by the flap procedure using adjacent tissue.

Plastic surgeons should consider the size, location, damaged structures, and the availability of surrounding skin when reconstructing defects. The patient's age, accompanying disease, and cosmetic goals are also factors to be considered in the construction process [5,6]. Ideal reconstruction of the face has no stenosis or distortion after reconstruction and goodagreement of the skin tone.

A well-known bilobed flap is a useful method for rebuilding nasal defects. However, the bilobed flap has the defect of not concealing the scar, as it isnot only unable to cover the large nasal sidewall defect but also difficult to construct along the relaxed skin tension line (RSTL) [7]. In addition, the V-Y glabella flap is only applicable when the defect area is less than 15 mm, and it is impossible to cover the large nasal defect. For this reason, more complex reconstruction methods should be considered when reconstructing large nasal defects [8].

When rebuilding the nasal side wall and nose bridge, the cheek rotation flap has several advantages over the median forehead flap. The median forehead flap is very useful when reconstructing the nose, but the disadvantage is that the scar of the donor site is located in the center of the forehead and is visible from the front. However, the donor site scar of the cheek rotation flap is located lateral side of the face and not stands out from the frontal side, and postoperative satisfaction of patients was high. In addition, unlike forehead flap which performs in two or three stages regardless of the defect size, the cheek flap is an effective procedure due to its no needs of division surgery, shorter hospital stay, and low incidence of complications such as hematoma, seroma and flap necrosis.

The scar from the cheek rotation flap can be hidden inside of the RSTL, and even if the donor portion of the flap is covered with a skin graft, it can be hidden in preauricular area which is located in not frontal but lateral side of the face. The donor site of the flap sutured primarily 73.7% and covered by skin graft 26.3%.In elderly patients, the skin relax degree of cheek and neck is high, and theprimary suture of flap donor waseasily achieved without tension. Considering the high occurrence of skin tumors in the elderly, the cheek rotation flap has the advantage of reducing additional skin grafts at the donor site.

In this study, thenasal sidewall defect area was as large as average 12.6 cm2, and the cheek rotation flap has provided sufficient flap size enough to reconstruct nasal sidewall defect ranging above nasal bridge. The widely constructed flap is able to reach to the nasal bridge by rotating advancement and its suture can be achieved without tension. However, to achieve wide cheek flap, the flap design extends toward inferior lobule of auricle, and nasolabial sulcus, the pivot point of flap rotation, makes dog ear for sufficient blood supply. This dog ear could not be removed from the first operation because it serves as the base of the flap and provides a plentiful vascularity. A month later, the patient underwent simple revision surgery under local anesthesia and the dog-ear was completely removed and achieved the smooth nasolabial sulcus.

Moreover, skin and the mucous membrane grafted under the cheek flap had a good engraftment rate. The high engraftment rate of the transplanted tissue seems to be a result of the characteristics of the cheek flap, which is flexible, easy to manipulate and more stable with blood flow.

Reconstructing the large nasal sidewall defect ranging above nasal bridge was accomplished stably with lower tension by using the method of constructing wide cheek flap and advancing through dissection and undermining of the opposite nasal sidewall from the anterior of subcutaneous tissue.

As the skin of the lower eyelid and nasal sidewall is thin, the cheek flap which elevates thin distal skin flap had better cosmetic results. The flap that is elevated above the zygmatic arch is necrosis dangerous because of its thin thickness to protect the temporal branch of the facial nerve. However, as the flap is re-elevated in the upper layer of the SMAS from 1 cm below the zygmatic arch, the subdermal plexus was acquired and the survival rate was increased. There were two cases of venous congestion at the end of the flap, and this venous congestion was resolved using medical leech therapy.

The reconstructing the full thickness defects of both nasal sidewall and alar of nose is difficult, because the alar of nose is a compact structure consisting of skin tissue, cartilage, and mucosal tissue, and a supportive structure for the nostrils to stay open.

Composite graft of ear cartilage and skin can be considered as a reconstruction method of full thickness defects of alar of nose, but it has the limits of implantable tissue size. In this study, the reconstruction of full thickness alar groove defects was processed using the methods of fixing one end of alar groove bended titanium plate to pyriform sinus margin while the other end of the plate is buried to the flap part which will be alar of nose. Six months later the titanium plate was removed, and the shape of the nasal alar could well be maintained. This suggests that even after removing the titanium plate, the fibrous scar tissue around the titanium plate retained the alargroove relatively firmly (Fig. 6).

As the reconstructing a large facial defect requires a large cheek flap, usually the hair line is destroyed by crossing incision line over whisker. If the cheek flap including the partial whisker is rotated and advanced, the unnaturally ended hair line makes unnatural cosmetic results. In this study, whisker isconserved by flap designing which descends from the anterior of whisker following through the line to ascend posteriorly. Then, the flap is designed to descend again from preauricle and contain non-haired skin between auricle and whisker. Using this method, the position of the hair line was not changed, and the cosmetic result was good.

The larger the defect site, the larger the elevated flap size, and the greater possibility of hematoma below the flap donor area. Because of this, it is necessary not only electrocautery but also careful prevention of bleeding by binding blood vessels. Also, penrose drain tube should be inserted as much as possible under the flap, and hematoma should be prevented by light compression dressing, pain management and head elevation.

Usually, the medial lower eyelid defect including medial canthus reconstructed complexly including lower eyelid, tarsus and conjunctiva by fixingthe one end of flap to medial canthus after elevation above the SMAS, and transplanting complex of nasal septal cartilage and mucus membrane to posterior of the flap. However, in this study, skin, tarsus, and conjunctiva remaining in the lateral canthus were all transferred to the medial canthus and fixed to the medial tarsus (Fig. 2). At the same time, the lower eyelid ectropion was prevented, because the direction of the force in lower eyelid, which is the most important factor of ectropion occurrence, was pulled toward the fixed area, the medial tarsus [9].

The cheek rotation flap is a reliable and trustworthy surgical procedure, as it advanced from consecutive surgical procedure, which only reconstructs the restricted defect area, and is applicable in the case of the large defect area including medial and lateral canthus and nasal sidewall. The medial canthal defects were reconstructed successfully by the cheek rotation flap, which transferred the components of lateral lower eyelid (intact conjunctiva, tarsus and skin) and fixed those to medial canthus.When it comes to the lateral canthal defects, it was performed by using high arch shaped design and cheek mucus membrane grafts. For the large nasal sidewall defects, no necrosis of end side of the flap existed and survived through sufficient blood flow of facial arteries. However, the smooth nasolabial sulcus can only be made through revision surgery.

The Cheek rotation flap has been used to reconstruct medial and lateral canthi ldefects, and furthermore, the large defects of nasal sidewall can be reconstructed satisfactorily. Therefore, if a large defect of the nasal sidewall needs to be reconstructed, the cheek rotation flap may be considered as a flap of choice to replace the paramedian forehead flap.

References

1. Bokhari WA, Wang ST. Modified approach to the cervicofacial rotation flap in head and neck reconstruction. Open Otolaryngol J 2011;5:18-24.

2. Diffey BL, Langtry JA. Skin cancer incidence and the ageing population. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:679-680. PMID: 16120172.

3. Chinem VP, Miot HA. Epidemiology of basal cell carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:292-305. PMID: 21603813.

4. Shanoff LB, Spira M, Hardy SB. Basal cell carcinoma: a statistical approach to rational management. Plast Reconstr Surg 1967;39:619-624. PMID: 6026420.

5. Masic T, Lincender I, Dizdarevic D. Reconstruction of total and subtotal nose defects. Med Arh 2010;64:110-112. PMID: 20514779.

6. Garces JR, Guedes A, Alegre M, Alomar A. Bilobed flap for full-thickness nasal defect: a common flap for an uncommon indication. Dermatol Surg 2009;35:1385-1388. PMID: 19549184.

7. Pletcher SD, Kim DW. Current concepts in cheek reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2005;13:267-281. PMID: 15817406.

8. Kim JH, Kim JM, Park JW, Hwang JH, Kim KS, Lee SY. Reconstruction of the medial canthus using an ipsilateral paramedian forehead flap. Arch Plast Surg 2013;40:742-747. PMID: 24286048.

9. Tyers AG, Collin JR. Colour atlas of ophthalmic plastic surgery. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier; 2008.

Fig. 1

Cheek rotation flap. Modified cheek rotation flap for keeping the side burn in situ (oblique line area: defect area, dotted area: skin graft).

Fig. 2

A case with a medial canthal area defect. (A) An 82-year-old woman with basal cell carcinoma on the left medial canthal area; preoperative photograph. (B, C) Intraoperative photograph. (D) Immediate postoperative photograph. (E, F) Seventy-five-month postoperative photograph with eyes opened and closed.

Fig. 3

A case with a lateral canthal area defect. (A) A 75-year-old woman with recurrent basal cell carcinoma in her right lateral canthal area; preoperative photograph. (B) Intraoperative photograph. (C) Immediate postoperative photograph. (D) Six-month postoperative photograph with eyes open. The donor site was dissected and the primary closed.

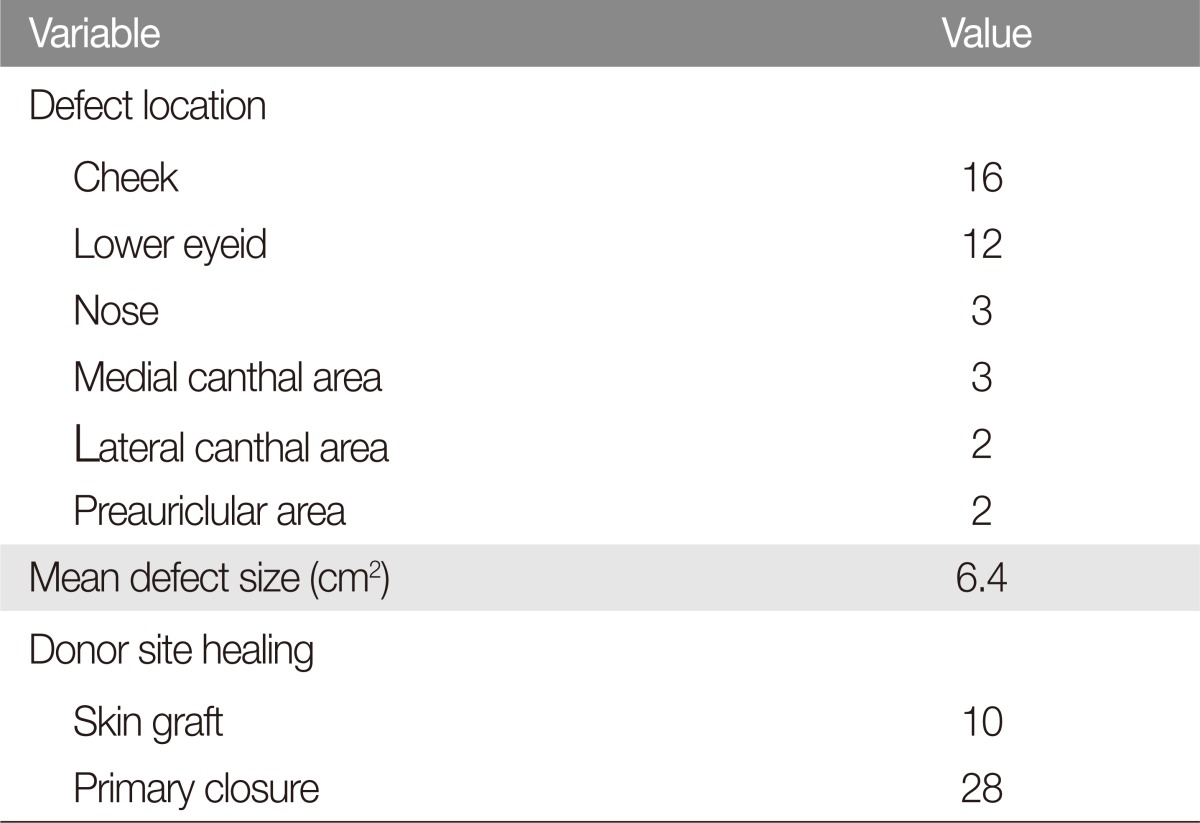

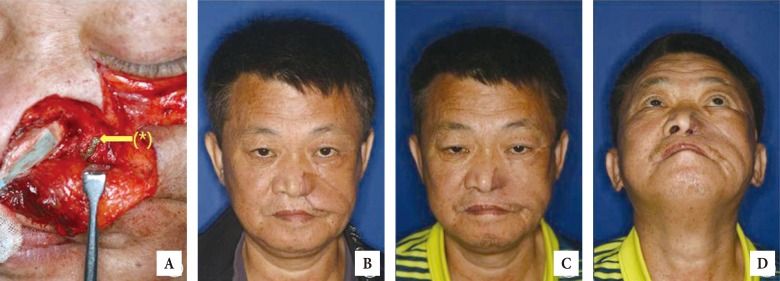

Fig. 4

A case with a large nasal sidewall defect. (A) A 87-year-old woman with squamous cell carcinoma on her left nasal sidewall; preoperative photograph. (B, C) Intraoperative photograph. (D) Eight-month postoperative photograph. from the left upper arm.

Fig. 5

A case with reconstruction of the damaged nasolabial sulcus back to its original form. (A, B) A 59-year-old man with basal cell carcinoma on his right nasal side wall; three-month postoperative photograph after cheek rotation flap. (C, D) Two-month postoperative photograph after wedge resection. Wedge resection was performed on his damaged nasolabial sulcus.

Fig. 6

A case with reconstruction of the frame of alar groove with titanium plate. (A) A 54-year-old man with left ala and left large nasal sidewall defect with cheek rotation flap using titanium plate (*); intraoperative photograph. (B) Postoperative photograph with left alar framework using titanium plate. (C, D) Four-month postoperative photographs after removal of titanium plate. Titanium plate removal and dog-ear excision were performed on his nasal ala and damaged nasolabial sulcus.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 12 Crossref

- Scopus

- 6,168 View

- 161 Download

- Related articles in ACFS

-

Dear Members of the Association2017 December;18(4)

The Treatment of the Large Palatal Fistula Using the Tongue Flap.2007 October;8(2)