|

|

- Search

| Arch Craniofac Surg > Volume 18(3); 2017 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

The conventional cervicofacial flap may cause the aesthetic problem of sideburns with a mismatched shape and arrangement. We developed a modified method with the goals of minimizing the destruction of the shape and arrangement of the sideburns and minimizing complications in comparison with the conventional method.

Methods

The incision line was designed to descend just in front of the sideburns, without passing through them, and then to ascend with the sideburns posteriorly when a cervicofacial flap is performed, unlike the conventional method. Patients in whom this method was applied (group B) and patients who underwent surgery using the conventional method (group A) were investigated in a retrospective study. The method was evaluated by assessing changes in the arrangement of the sideburns and patients' satisfaction, and differences in the complication rate.

Results

In group A, 23 of the 31 patients experienced changes in the arrangement of their sideburns. Most patients who experienced a change in the arrangement of their sideburns were dissatisfied with the change. The patients in group B did not experience such changes, and the defects were well reconstructed. Most of them were satisfied with the final sideburn arrangement.

Conclusion

A novel method was used to preserve the sideburns while performing a cervicofacial flap. As a result, the appearance of the sideburns was well preserved and the satisfaction of patients was also high. Moreover, this technique could also prove useful for reconstruction without any increase in complications compared to the conventional method.

First implemented by Mustarde [1], cervicofacial flaps have been widely used to reconstruct soft tissue defects on the cheek. These flaps can be separated into the anterior-based flaps introduced by Juri and Juri [2], which receive blood flow from facial or submental arteries, and the posterior-based flaps introduced by Stark and Kaplan [3], which receive blood flow from the superficial temporal or the preauricular arteries. These flaps utilize excess skin and tissue on the neck or the cheek, allowing for easy manipulation. They have also been widely used for the reconstruction of lower eyelid and medial and lateral canthal area defects due to their great flexibility [4].

The incision for anterior-based flaps typically begins at the superior boundary of the cheek, passes through the sideburns, and follows the preauricular crease downwards. However, this standard operation changes the shape and arrangement of the sideburn, which is a critical anatomical structure that defines the facial boundaries, and could potentially cause aesthetic issues. If this small area is missed or distorted, the patient's appearance, especially from the side of the face, could be greatly altered [5].

The authors of this paper attempted (1) to minimize the destruction of the shape and arrangement of the sideburns, and (2) to minimize complications when compared to the conventional method during the utilization of the cervicofacial flap in reconstruction procedures performed after the excision of skin cancer on the cheek, lower eyelid, and sidewall of the nose. Using this as a foundation, the authors sought to develop a procedure to preserve the shape of the sideburn while retaining the effectiveness of the cervicofacial flap, and to demonstrate its effectiveness in a clinical trial.

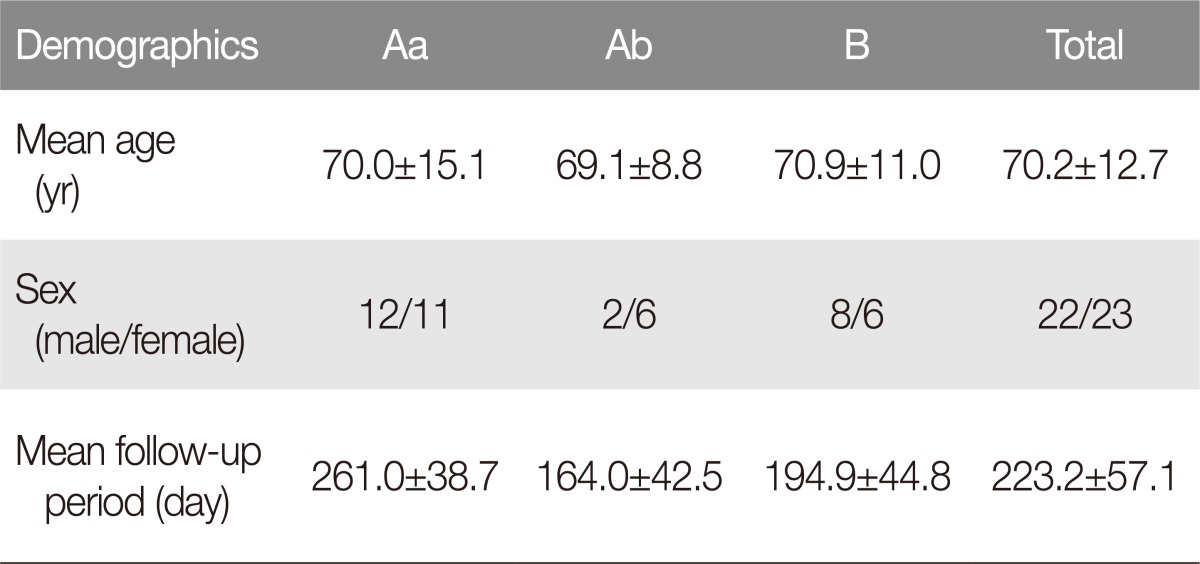

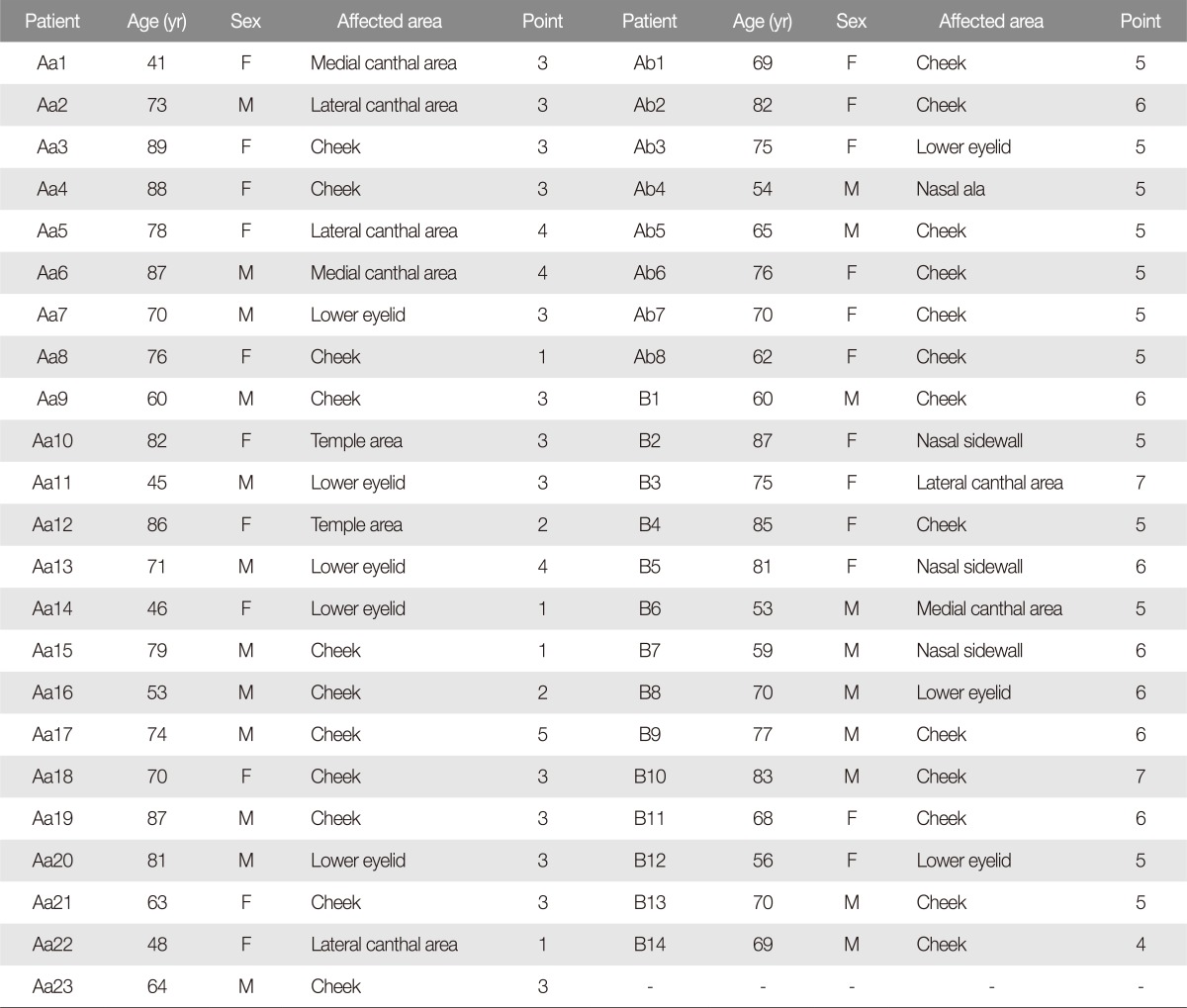

A retrospective study was conducted of patients who underwent cervicofacial flap surgery after the surgical removal of malignant tumors on the face from January 2014 to December 2016. The patients were separated into 2 groups. The first group (group A) consisted of patients who underwent surgery using the existing cervicofacial flap procedure, with one subgroup (Aa) consisting of those who experienced sideburn deformation and another subgroup (Ab) consisting of patients without sideburn deformation. The second group (group B) consisted of patients who underwent surgery with the goal of minimizing sideburn deformation. Group A had a total of 31 individuals, with 23 in subgroup Aa and 8 in subgroup Ab. Group B had a total of 13 individuals. The age of the patients in subgroup Aa was 70.0Âą15.1 years, and that of subgroup Ab was 69.1Âą8.8 years. Group B had an age range of 53 to 87 years, with an average age of 70.9Âą11.0 years. The average follow-up period for subgroup Aa was 261.0Âą38.7 days, with 164.0Âą42.5 days for subgroup Ab. The average follow-up period was 194.9Âą44.8 days for group B (Table 1). All surgery was conducted under general anesthesia by a single surgeon.

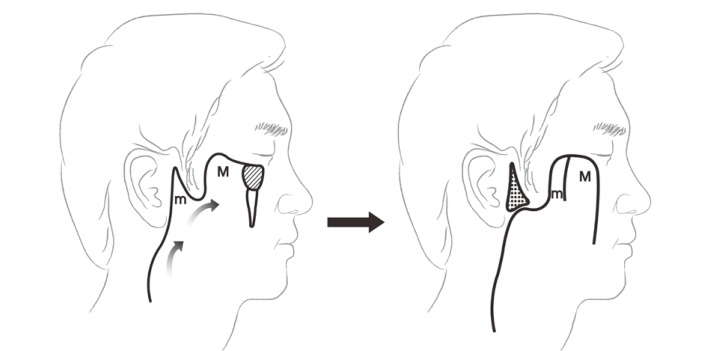

Prior to cervicofacial surgery, the members of group A underwent an incision that traveled transversely from the defect, passed through the lateral canthus, the preauricular crease, and earlobe, and stopped below the occipital hairline. In the members of group Aa, the sideburn range or defect size was large enough to force the incision line to pass straight through the sideburns, resulting in the displacement of the sideburn. In contrast, the members of group Ab had either a small defect size or small sideburns, allowing the transverse incision to be made without passing through the sideburn. Group B had an incision line that went straight down from the sideburns, followed the sideburns to the rear, and moved upwards. This path was taken regardless of the position or size of the sideburns. This method resulted in 2 different cervicofacial flaps: the major cervicofacial flap and the minor preauricular flap.

The flaps were elevated above the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) layer and the defect was reconstructed by rotation and advancement, maintaining its subdermal vascular plexus. After positioning the flap on the defect, the external incision line was extended in the inferomedial direction to maximize the medial rotation of the flap. The minor flap was approximated to the major cervicofacial flap and attached (Fig. 1). The donor site of the small flap was covered either by undermining the remaining subcutaneous tissue in the cervicofacial region to stitch it together with the flap or by a skin graft. Hemostasis using electrocautery and ligation was used to prevent hematoma. In addition, Penrose drain tubes were inserted sufficiently at the lower end of the flap at the end of the surgical procedure, along with a pressure dressing.

Both groups A and B were evaluated using 2 methods. The first method was by observing the sideburn arrangement of each patient in follow-up examinations and surveying the patient's satisfaction with their sideburns. A score was obtained ranging from 1 to 7 points, with 5 points or above indicating satisfaction and 3 points or below indicating dissatisfaction. The second method was investigating the incidence of hematoma, necrosis, hair loss in the sideburns, and other complications during the postoperative period and during the follow-up period in both groups and comparing their proportions.

In group A, 23 of the 31 patients showed advancement of a portion of the distal part towards the cheek (Fig. 2). The degree of change varied among patients based on the location and size of the defect. Within group A, the patients in subgroup Aa, who experienced changes in the sideburns, indicated dissatisfaction with the changes, with an average score of 2.78Âą1.04. Of these individuals, 6 patients gave a score below 2, indicating a severe level of dissatisfaction. However, 3 patients accepted the inevitability of the situation due to the nature of skin cancer removal surgery, while the remaining 3 patients underwent operations such as laser treatment after consultation with the authors. The 8 patients in subgroup Ab, who did not experience any changes in their sideburns, showed relative satisfaction, with an average score of 5.13Âą0.35 (Table 2).

The patients in group B did not exhibit any significant changes in their sideburns and experienced a successful reconstruction of the defect. As a result, of the 14 patients in group B, 13 patients (approximately 93%) reported a score of 5 or higher, and even the 1 remaining patient had a score of 4. The average score in group B was 5.64Âą0.84 (Table 2). The Mann-Whitney U-Test was conducted in SPSS ver. 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to compare the satisfaction scores of group Aa with those of groups Ab and B combined. The p -value was less than 0.05, indicating a statistically significant relationship between sideburn deformation and patient satisfaction.

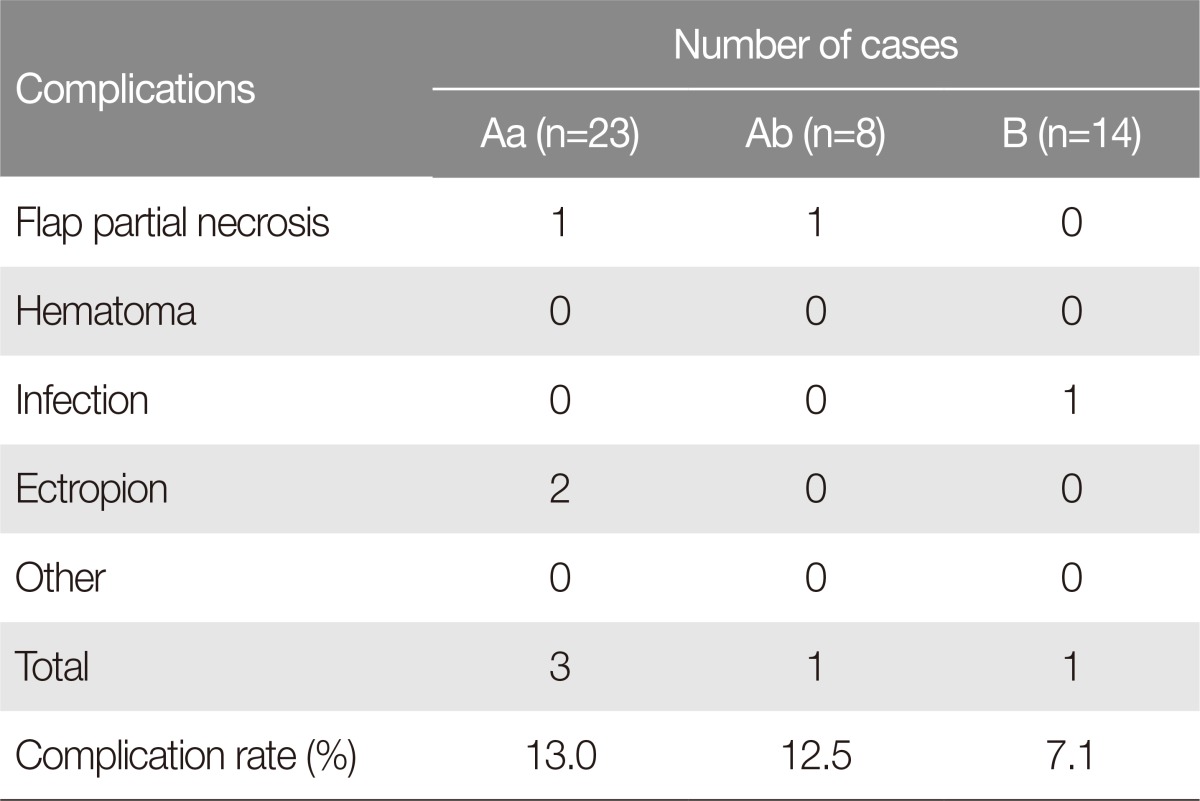

In group A, 4 of the 31 patients suffered from partial necrosis or ectropion, resulting in a complication rate of 12.9% (4 of 31). Two individuals showed partial necrosis in the distal part of the flap and recovered through debridement and dressing. The other 2 patients showed ectropion, which was adjusted using a full-thickness skin graft and lateral canthoplasty. Subgroup Aa contained 1 patient with partial necrosis of the flap and 2 patients with ectropion, while subgroup Ab contained 1 patient with partial necrosis of the flap. Hence, the complication rates for subgroups Aa and Ab were 13.0% and 12.5%, respectively (Table 3).

Although 1 patient in group B had an infection due to wound contamination, it was resolved through antibiotics. There were no cases of partial necrosis of the flap, hair loss, or facial nerve paralysis, resulting in a complication rate of 7.1% (1 of 14) (Table 3).

The Fisher test for the complication rates of group A and group B showed a positive result of 1.00, meaning that there was no significant difference in the complication rate according to the surgical method.

Cook et al. [6] emphasized that when a surgical method for midface and cheek reconstruction is chosen, the skin contours and texture, as well as the texture and the flexibility of the tissue, must be taken into consideration. Furthermore, they also stressed the importance of choosing a method that minimizes the distortion of the eyes and upper lip, while leaving facial movements unaffected. Cervicofacial flap surgery is a method that satisfies that criterion. Such surgery can be performed using an anterior-based flap or a posterior-based flap, depending on where the flap is based. The anterior-based flap was generally used by the authors, and the cervicofacial flap procedures performed on the patients in this study were all anterior-based flaps, with slight variations in the shape and size of the flap based on the size and position of the defect. This flap procedure is relatively easy, allows for the coverage of large defects, has clear areas of blood flow, and can be used to reconstruct not only defects in the cheek, but also in the lower eyelid and the medial and lateral canthus [4].

The sideburns are anatomical structures that define the facial boundary. Hence, changes in the arrangement of the sideburns can lead to significant changes in an individual's appearance [5]. As can be seen from the results of this study, changes in the sideburns are very difficult for patients to accept. Hence, the authors of this paper have changed the flap design to minimize the changes in the sideburn arrangement while maintaining the versatility of cervicofacial flap surgery (Fig. 1). The design moves transversely from the defect, and does not pass through the sideburns, but rather follows the medial boundary of the sideburn downwards, follows the lateral boundary upwards, and heads toward the preauricular crease. After an incision was made in the shape of the flap design, it was elevated and the defect was covered using rotation and advancement. The minor flap placed between the lateral boundary of the sideburn and the preauricular crease was advanced and attached to the major flap by crossing over the sideburn. The donor site of the minor flap was sutured or covered using a skin transplant. This method allowed the patients to preserve the arrangement of their sideburn area. Because the flap donor site between the preauricular crease and the sideburn was covered by suturing or a skin transplant, the sideburn was pulled slightly posteriorly, but not to a noticeable extent.

The primary concern that the authors had when developing this method was necrosis due to restricted blood flow in the minor flap when advancing the minor flap towards the major flap. However, due to the excellent blood flow capacity of the cervicofacial flap, no cases of flap necrosis whatsoever occurred. In addition, the method was also used successfully not only to reconstruct the cheek, lateral and medial canthus, and lower eyelids, but also the nasal sidewall (Table 2) (Fig. 3, 4, 5).

A major disadvantage of cervicofacial surgery is the fact that, like other types of flap surgery, partial necrosis can occur in the flap tips. Moore et al. [7] reported that of the 35 patients who underwent cervicofacial flap surgery, 3 (9%) experienced full-thickness necrosis in the flap tips. Austen et al. [8] stated that 3 of the 32 patients in their study (9.4%) experienced minor partial necrosis of the flap tips. Liu et al. [9] likewise reported that of the 21 patients who received cervicofacial flap surgery, 2 (9.5%) experienced necrosis in the flap tip. In addition to partial necrosis, hematoma, infection, and scars can occur after the operation. When reconstructing a defect in the lower eyelids or the cheek, ectropion can also occur due to gravity and scar contracture. In addition, when lifting the flap, the incision was made by choosing the preauricular crease as the lateral margin of the flap and crossing the sideburn to form the superior margin. Hence, some deformation of the arrangement of the sideburn could occur. In other words, the sideburn is excised to form multiple levels (Fig. 2).

In terms of complications, group A, in which existing surgical methods were used, contained 2 patients with partial necrosis and 2 patients with ectropion. The total complication rate of this group was 12.9%. When group A was further divided into subgroups Aa and Ab, subgroup Aa had a complication rate of 13%, with 1 case of partial necrosis and 2 cases of ectropion, while subgroup Ab had a rate of 12.5%, with 1 case of partial necrosis. In group B, in which the method designed to preserve the sideburn was used, there was only 1 case of wound infection, resulting in a complication rate of 7.1%. The Fisher test resulted in a p-value of 1.00, indicating that there was no correlation between the patient group and the complication rate. No other complications occurred. This is because cervicofacial flap surgery involves good blood flow capacity and flexibility, allowing the flap to be divided in two without increasing the possibility of complications due to flap necrosis and reduced blood flow.

Recently, methods to increase blood flow to the flap using deep planes have been implemented in cervicofacial flap surgery. Tan and MacKinnon [10] lifted the flap just deep to the SMAS, but the flap tip necrosis rate was still 6% (1 of 18) overall. In addition, because the method utilized deeper levels, it had the disadvantages of a long operative time, a high chance of damaging the temporal branch of the facial nerve, and requiring a very experienced surgeon [8]. Hence, the authors of this paper followed the traditional method and lifted the flap shallower than the SMAS, which resulted in better blood flow and flap mobility, ultimately resulting in a lower rate of flap tip partial necrosis. Among all the patients included in this study, the flap partial necrosis rate was only 4.4% (2 of 45).

References

1. Mustarde JC. The use of flaps in the orbital region. Plast Reconstr Surg 1970;45:146-150. PMID: 5411895.

2. Juri J, Juri C. Advancement and rotation of a large cervicofacial flap for cheek repairs. Plast Reconstr Surg 1979;64:692-696. PMID: 504491.

3. Stark RB, Kaplan JM. Rotation flaps, neck to cheek. Plast Reconstr Surg 1972;50:230-233. PMID: 4559210.

4. Bokhari WA, Wang SJ. Modified approach to the cervicofacial rotation flap in head and neck reconstruction. Open Otolaryngol J 2011;5:18-24.

5. Yang Z, Fan J, Tian J, Liu L, Gan C, Chen W, et al. Aesthetic sideburn reconstruction with an expanded reversed temporoparieto-occipital scalp flap. J Craniofac Surg 2014;25:1168-1170. PMID: 25006889.

6. Cook TA, Israel JM, Wang TD, Murakami CS, Brownrigg PJ. Cervical rotation flaps for midface resurfacing. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:77-82. PMID: 1986766.

7. Moore BA, Wine T, Netterville JL. Cervicofacial and cervicothoracic rotation flaps in head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck 2005;27:1092-1101. PMID: 16265654.

8. Austen WG Jr, Parrett BM, Taghinia A, Wolfort SF, Upton J. The subcutaneous cervicofacial flap revisited. Ann Plast Surg 2009;62:149-153. PMID: 19158524.

9. Liu FY, Xu ZF, Li P, Sun CF, Li RW, Ge SF, et al. The versatile application of cervicofacial and cervicothoracic rotation flaps in head and neck surgery. World J Surg Oncol 2011;9:135PMID: 22018437.

10. Tan ST, MacKinnon CA. Deep plane cervicofacial flap: a useful and versatile technique in head and neck surgery. Head Neck 2006;28:46-55. PMID: 16302190.

Fig. 1

Cervicofacial flap incision line design. The preauricular minor flap (m) is approximated to the major cervicofacial flap (M), and the donor site of the minor preauricular flap is closed primarily if possible. If this area cannot be closed, it is covered with a split-thickness skin graft.

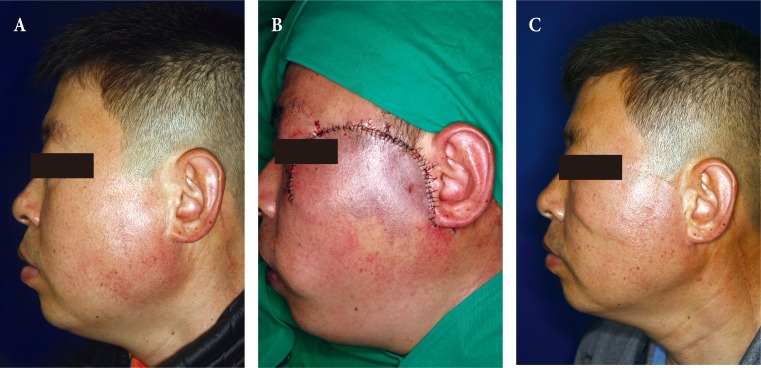

Fig. 2

A case of conventional cervicofacial flap. (A) 45-year-old man who had lentigo maligna on the left lower eyelid. (B) He underwent excision and the defect was covered with a cervicofacial flap. (C) Follow-up photo after 78 months. His sideburn was divided and the distal part was moved in the anterior direction. He solved this problem by cutting his sideburns to be short.

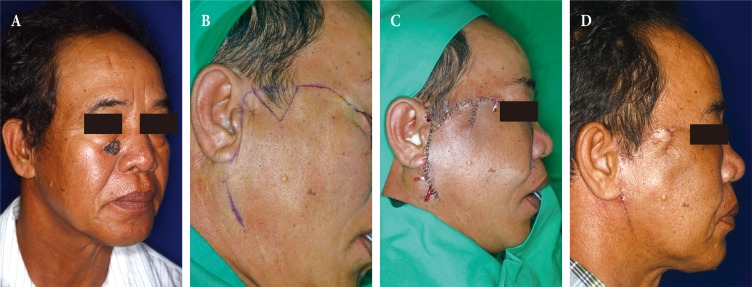

Fig. 3

A case of modified cervicofacial flap. (A) 60-year-old man who had basal cell carcinoma on his right cheek. He underwent excision and a cervicofacial flap using the new method. (B-C) Incision line design and results of this method. The minor preauricular flap (m) was advanced to the major cervicofacial flap (M). The donor site of the minor preauricular flap was closed primarily. (D) Follow-up photo 1 month after the operation. It is clear that the arrangement of the sideburn was not altered.

Fig. 4

A case of nasal sidewall reconstruction. (A) A 59-year-old man who had a black patch on his right nasal sidewall. It was histopathologically confirmed to be squamous cell carcinoma (B) He underwent excision, and the defect was covered with a cervicofacial flap. The donor site was covered by a split-thickness skin graft. (C) Follow-up photo after 44 months. The defect was covered effectively with the native sideburn, and no complications had developed.

Fig. 5

A case of lower eyelid reconstruction. (A) A 70-year-old man who had a mass on his right lower eyelid. It was histopathologically confirmed to squamous cell carcinoma. (B) He underwent excision and the defect was covered with a cervicofacial flap. The donor site was closed primarily. (C) Follow-up photo after 32 months.

Table 2

Satisfaction point of each patient

Aa average, 2.78Âą1.04; Ab Average, 5.13Âą0.35; B Average, 5.64Âą0.84.

Aa, patients who underwent the conventional method with altered arrangement of sideburn; F, female; Ab, patients who underwent the conventional method without altered arrangement of sideburn; M, male; B, Patients who underwent the new method for preserving arrangement of sideburn.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- Scopus

- 5,848 View

- 79 Download

- Related articles in ACFS