Paraffinoma induced bilateral preauricular cheek skin defects

Article information

Abstract

“Paraffinoma” is a well-recognized complication of paraffin oil injection into various body parts for an aesthetic purpose. After a variable latency phase, paraffinoma can present as a wide range of clinical symptoms. This paper is a case report of surgical excision of the paraffinoma and subsequent reconstruction of the associated skin defect on bilateral preauricular cheeks, manifesting 50 years after a primary injection.

INTRODUCTION

First discovered by von Reichenbach in 1830 [1], paraffin is a purified mineral oil whose primary purpose was to serve as a vehicle for oil-soluble substances [2]. Facial augmentation can be achieved using various materials, and in the past, liquid paraffin was deemed a simple and effective method [3]. Liquid paraffin is injected into not only the cheeks, but also other body parts including nose, breasts and penis in order to fill the tissue or contour defects, or purely for an aesthetic volume supplementation [4].

“Paraffinoma” is an adverse consequence of injecting the paraffin oil. Despite being regarded as an unsound therapy, paraffin oil injection is still practiced these days by nonphysicians and cosmetologists not so rarely. In addition, the duration of latent phase is variable, manifesting as long as 10 to 20 years later [5-7]. In this sense, it would not be infrequent to encounter patients with paraffinoma or associated symptoms in a real clinical practice nowadays.

In this paper, we are reporting a case of a female patient with a skin defect on bilateral cheeks and exposed foreign body granuloma after paraffin oil injection approximately 50 years ago. No previous case report dealt with bilateral, symmetrical skin defects on preauricular cheeks due to paraffinoma.

CASE REPORT

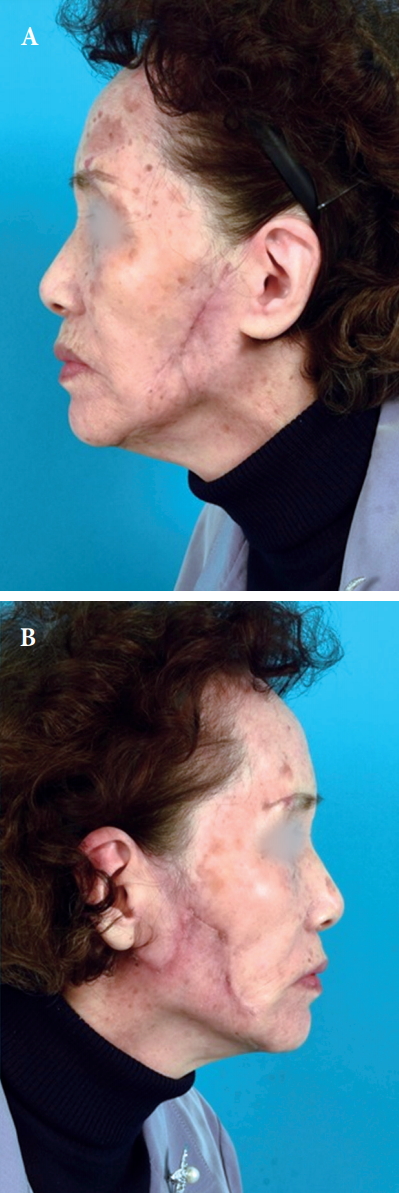

An 82-year-old female patient was referred from the Department of Dermatology for a skin defect on bilateral preauricular cheeks. History taking revealed an injection of unidentifiable substances approximately 50 years ago. Over the last 20 years, there has been a progressive skin thinning with telangiectasia on both injection sites. Eventually, since 2006, overlying skin has started to peel off, exposing the underlying foreign body granuloma. Skin defect on both sides gradually increased in their sizes, and at initial presentation, the right and left side defect measured up to 4.0×3.5 and 3.0×2.5 cm, respectively (Fig. 1). Prior to referral to our clinic, no previous surgical treatment has been attempted.

Preoperative photograph. Bilateral preauricular cheek skin defects with exposed paraffinoma in two different projections. (A) Left and (B) right.

There was no significant previous medical, other operation or medication history worth of mentioning. Her preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grading was class I. According to the preoperative physical examinations, all facial motors and sensory were normal. Underneath the skin defect on each side, there was a palpable and non-movable mass-like lesion.

Preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan revealed a multi-focal radiopaque lesion with multiple punctate calcifications on bilateral preauricular cheeks, superficial to masseter muscle. Adjacent structures such as parotid gland were deviated from the normal location due to mass effect.

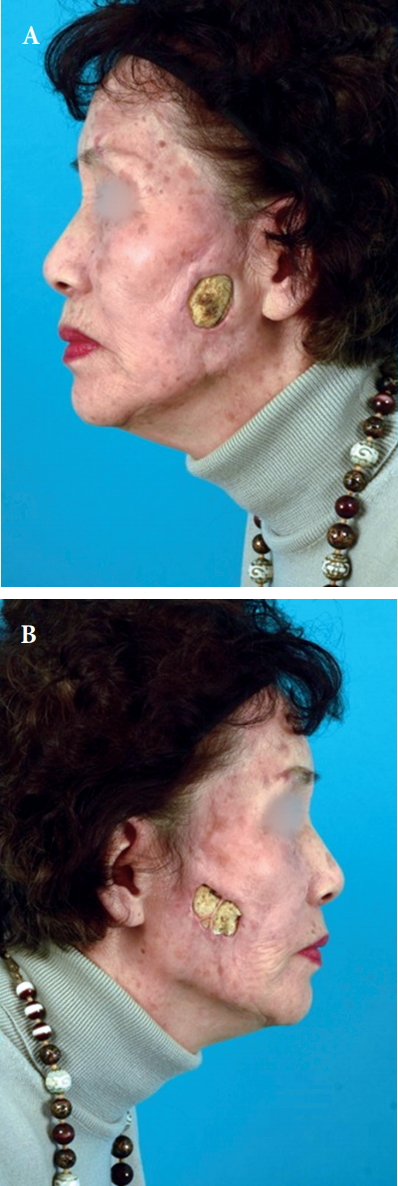

Under general anesthesia, via open defect on each side, the extent and boundary of foreign body were identified. Foreign body was removed, one side at a time, with caution not to damage the nearby structures, especially facial nerve main trunk and branches, and parotid gland. During the process of removal, nerve stimulator monitoring guided the navigation of the probable facial nerve location and pathway. Overall, lesions were well-demarcated from the surroundings, and they were completely excised (Fig. 2). Then, each defect margin was debrided. On the left side, an extended incision was made, and primary closure was possible thanks to the skin laxity (Fig. 3A). On the opposite side, however, lower eyelid ectropion was anticipated upon primary closure. Hence, Limberg flap was adopted for the closure of the defect (Fig. 3B). Wound was closed by layers after insertion of a negative-pressure closed-suction drain in each side. Overall, the surgery went uneventful.

Surgical specimens. Excised paraffinoma specimen from the right (Rt) and left (Lt) preauricular cheeks.

Remnant skin defect after the removal of paraffinoma. (A) On the left cheek, extended incision was made and primary closure was done. (B) On the right cheek, Limberg flap was used to close the defect.

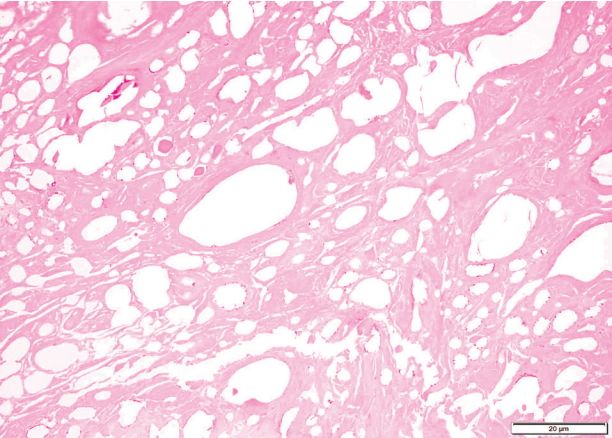

During the postoperative periods, skin flaps, especially on the right side was closely monitored. No congestive margins were noted. Postoperative physical examinations revealed no suspicious injury on the facial motor functions. The day after surgery, both drains were removed, and patient was discharged from the hospital. On out-patient clinic, all stitches were removed at the seventh day postoperatively. Permanent biopsy proved both lesions to be consistent with a paraffinoma (Fig. 4). A 4-month follow-up showed a tolerable reconstructive result (Fig. 5).

H&E stained specimen (×20). Round or oval shaped empty pseudo-cysts encompassed by lymphocytes, epithelioid cells and giant cells.

DISCUSSION

Paraffinoma is defined as a chronic granulomatous inflammatory reaction [8]. It bears a clinical significance in that it can infiltrate into the nearby structures and initiate all sorts of clinical symptoms such as pain, palpable mass, skin ulceration which can lead to skin defect, sinus opening or fistula formation leading to suppuration, lymphadenopathy, and although very rare, even malignant degeneration [8-12]. Pathological examination of the specimen is the definite diagnostic tool of the paraffinoma. Typical features of paraffinoma in hematoxylin and eosin staining include round or oval shaped empty pseudo-cysts encompassed by lymphocytes, epithelioid cells and giant cells [13].

Paraffinoma is still occasionally encountered in the clinical practice, as some nonphysicians and cosmetologists still practice the injection of paraffin oil these days, and the past injections become clinically apparent in the present days after a significant period of latent phase. The paraffin oil is known to be refractory to all kinds of lysozymal enzymes and substances, and eventually, it forms a chronic inflammatory granuloma, which can cause a wide range of morphological disfigurements including a skin defect, as in this case [8]. Treatment of paraffinoma is still problematic nowadays, especially in the case of a diffuse infiltration into normal adjacent structures [13]. Yet, the golden standard treatment of paraffinoma remains the surgical excision, in most cases [10,11,14]. Complete surgical excision is the only way to avoid the recurrence.

In this particular case, the involvement of facial nerve was of the most concern. Moreover, caution was paid not to damage the facial nerve during the process of excision. Preoperative physical examinations revealed no impairment in the facial motors or sensations in the patient. Fortunately, no postoperative impairment was noted. Intraoperatively, structures assumed to be parotid gland and facial nerve main trunk were found to be deviated from their normal location as a result of the paraffinoma’s mass effect. However, the margin demarcating the granuloma from these structures was relatively well-defined, and thus, surgical excision came handier than expected.

This paper deals with a clinical case, in which bilateral preauricular cheek skin defects were complicated in an 82-year-old female as a result of a paraffin oil injection 50 years ago. The symmetrical nature of the presentation, very long period of latent phase approximating to 50 years, and finally, successful reconstruction using regional structures whilst preserving the facial motor function all combine to add a clinical significance to the case.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Notes

PATIENT CONSENT

The patients provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of their images.