|

|

- Search

| Arch Craniofac Surg > Volume 22(2); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

Pediatric nasal fractures, unlike adult nasal fractures, are treated surgically as early as 7 days after the initial trauma. However, in some cases, a week or more elapses before surgery, and few studies have investigated the consequences of delayed surgery for pediatric nasal fractures. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the postoperative outcomes of pediatric nasal fractures according to the time interval between the initial trauma and surgery.

Methods

The records of pediatric patients under 12 years old who underwent closed reduction of nasal bone fracture from March 2012 to February 2020 were reviewed. The interval between trauma and surgery was divided into within 7 days (early reduction) and more than 7 days (delayed reduction). Postoperative results were classified into five grades (excellent, good, moderate, poor, and very poor) based on the degree of reduction shown on computed tomography.

Results

Ninety-eight patients were analyzed, of whom 51 underwent early reduction and 47 underwent delayed reduction. Forty-two (82.4%) of the 51 patients in the early reduction group showed excellent results, and nine (17.6%) showed good results. Thirty-nine (83.0%) of the 47 patients in the delayed reduction group showed excellent results and eight (17.0%) showed good results. No statistically significant difference in outcomes was found between the two groups (chi-square test p=0.937). However, patients without septal injury were significantly more likely to have excellent postoperative outcomes (chi-square test p<0.01).

Nasal fractures are not common in very young children because of childrenŌĆÖs underdeveloped nasal skeleton and the relatively thick soft-tissue envelope, as well as the fact that young children are closely supervised by their parents. Nonetheless, nasal fractures are the most common type of facial fracture in the pediatric population [1-3].

Nasal bone fractures in pediatric patients need earlier reduction than those in adults; the general recommendation is for reduction to be performed 3 to 7 days after the initial trauma [1,4,5], because the accelerated healing process of the pediatric nasal skeleton could make later reduction challenging [1,4,5].

Previous studies of pediatric nasal fractures have investigated the incidence, etiology, treatment options, and outcomes [3,6-8], but few reports have analyzed the time interval between injury and reduction or presented objective results based on computed tomography (CT) images of pediatric patients.

Therefore, to provide information on the proper timing of reduction for nasal bone fractures in the pediatric population, we investigated whether surgical outcomes were different according to whether pediatric patients underwent early or delayed reduction of nasal bone fractures.

We reviewed the medical records of pediatric patients (12 years old and younger) with isolated nasal fractures who were treated from March 2012 to February 2020. Patients who had closed reduction and underwent postoperative CT examinations upon parental request were included in this study, while patients were excluded if they had previously undergone nasal surgery, had a history of previous nasal fractures, or had another facial bone fracture accompanying the nasal fracture.

Fractures were classified using the Stranc and Robertson system, as follows: frontal impact type I (FI) and type II (FII); lateral impact type I (LI) and type II (LII); and comminuted [9]. The interval between the initial injury and surgery was divided into within 7 days (early reduction) and more than 7 days (delayed reduction). and the postoperative outcomes were evaluated based on the degree of reduction shown on CT images.

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Between-group comparisons of proportions were made using the chi-square test. A p-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

The postoperative results were evaluated as excellent, good, fair, poor, or very poor according to the presence of malalignment of the fracture, fracture segment irregularity, and bony displacement.

The outcome was considered excellent if there was no malalignment of the fracture segment, bony irregularity, or displacement, and good if there was mild malalignment of the fracture segment with one segment of bony irregularity or displacement. A fair outcome was defined as an irregular nasal pyramid with malalignment, bony irregularity, and displacement (Table 1) [10].

Ninety-eight patients met the inclusion criteria, of whom 66 were boys and 32 were girls. The patients ranged in age from 2 to 12 years, and their mean age was 8.4 years old. The most common etiology of injuries was a bumping accident, followed in descending order by slipping down, a sports accident, a traffic accident, and falling down. The interval from the injury to surgery ranged from 2 to 25 days (mean, 7.9 days).

Fifty-one patients underwent early reduction, and 47 underwent delayed reduction. All reduction procedures were performed under general anesthesia. The mean age of patients in the early reduction group was 8.53 years, while the mean age in the delayed reduction group was 8.23 years. The mean interval until reduction was 5.67 days in the early reduction group and 10.21 days in the delayed reduction group (Table 2). In the early reduction group, 15 patients underwent surgery within 5 days and 36 patients underwent surgery at 6 or 7 days after the injury. In the delayed reduction group, 34 patients underwent surgery within 10 days after the injury, 11 patients underwent surgery between 11and 14 days post-injury, one patient underwent surgery at 18 days, and one underwent surgery at 25 days.

The distribution of fracture types according to the Stranc and Robertson classification in the 51 patients who underwent early reduction was as follows: type FI, 21 patients; type LI, 24 patients; type FII, three patients; and type LII, three patients. Forty-two patients (82.4%) had excellent postoperative outcomes, while nine patients (17.6%) had good outcomes (Table 3). Among the 47 patients who underwent delayed reduction, 16 had type FI fractures, 27 had type LI fractures, two had type FII fractures, and two had type LII fractures. The postoperative outcomes were excellent in 39 patients (83.0%) and good in eight patients (17.0%). There was no statistically significant difference in postoperative outcomes between the early and delayed reduction groups (chi-square test p=0.937).

In the early reduction group, eight patients (15.7%) showed septal fracture or deviation, whereas seven patients (14.9%) in the delayed reduction group had a septal injury. Patients without septal injury were significantly more likely to have excellent postoperative outcomes (chi-square test p<0.01) (Table 4).

Although maxillofacial injuries are relatively uncommon in the pediatric population, nasal bone fractures account for between 41% and 63% of all fractures in pediatric patients [11,12], and the incidence of pediatric nasal bone fractures increases with age [13]. These epidemiological characteristics of pediatric nasal bone fractures are due to anatomical and behavioral factors. Relevant anatomical factors include (1) underdevelopment and flexibility of the nasal skeleton, (2) immaturity of the paranasal sinus, and (3) a prominent buccal fat pad [14]. Behavioral factors include (1) low-impact falls due to childrenŌĆÖs low height, (2) close supervision by parents, and (3) an increasing incidence with age due to the increased involvement of older children in recreational activities [15].

Although pediatric nasal injuries are uncommon for the above reasons, they pose clinical challenges in terms of the difficulty of diagnosis, reduction, and determining the timing of reduction. Pediatric nasal fractures are difficult to diagnose due to severe soft-tissue edema, which may mask underlying fractures. Previous reports found that simple X-rays had low sensitivity for the diagnosis of pediatric nasal bone fractures, while CT scans were highly sensitive [1,15]. However, CT scans have the disadvantage of exposing pediatric patients to higher doses of ionizing radiation. Therefore, we only performed CT examinations if patientsŌĆÖ parents wanted to check the postoperative results using CT scans, and analyzed the outcomes among those patients.

The difficulty of the reduction procedure itself and the choice of when to perform surgery are also challenges. It is generally thought that reducing pediatric nasal fractures is especially difficult due to the small, resilient, and low-projected nasal skeleton, and that reduction should be performed earlier than for adult nasal fractures because children exhibit faster osteogenesis [1,4,5]. The accelerated process of healing in children may limit the efficacy of closed reduction when the procedure is performed 6 days or later after the injury [16], and many surgeons have conventionally considered that reduction should therefore be performed within 3ŌĆō7 days in pediatric patients [1,4,5]. However, few studies have provided evidence that delayed reduction (more than 7 days after the injury) is more likely to lead to unsuccessful surgical results based on a comparison of outcomes between early and delayed reduction.

Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the postoperative results of pediatric patients with nasal bone fractures based on CT imaging and investigated whether the outcomes differed according to the time elapsed from the injury to reduction. The study was limited to pediatric patients 12 years of age and under because when children approach adolescence, their pattern of nasal fractures becomes more similar to that of adults [1].

Of all 98 patients, 51 (52.04%) underwent early reduction and 47 patients (47.96%) underwent delayed reduction. Of the 42 patients with excellent results in the early reduction group, 38 showed no septal injury and four had a septal injury. Of the nine patients with good results, five showed no septal injury and four had a septal injury. In the delayed reduction group, of the 39 patients with excellent results, 36 showed no septal injury and three had a septal injury. Of the eight patients with good results, four showed no septal injury and four had a septal injury. In the delayed reduction groups, almost all procedures were performed within two weeks, with the exception of two cases performed at delays of 18 days and 25 days after the initial injury; nonetheless, those cases showed excellent postoperative results (Figs. 1, 2). No statistically significant difference in outcomes was found between the early and delayed reduction groups (p=0.937). In cases of good results, regardless of the timing of reduction, CT scans showed multiple irregular fracture segments with no septal injury or simple fracture segments with a septal injury. Patients without septal injuries were significantly more likely to have excellent postoperative results (p<0.01).

Another challenge related to pediatric nasal fractures is posed by greenstick or imprinted fractures, which refer to incomplete fractures, particularly in infants or young children. In cases of greenstick fractures, the fracture segment is often not clearly identified; however, the condition of the fracture can be evaluated by checking abnormal bending or asymmetric bending on CT scans converted from two-dimensional to three-dimensional views. Greenstick fractures develop due to immature, soft, and resilient bone with thick and fibrous periosteum, and they may lead to incomplete repositioning of bone fragments or under-correction [8,17]. Four cases of typical greenstick or imprinted fractures were found in this study, all of which demonstrated incomplete repositioning of fracture segments into the pre-traumatic position regardless of the timing of reduction (Fig. 3).

Although osteogenesis is fast in the pediatric population, the nasal skeleton is thin and soft, which may explain why pediatric nasal fractures can be reduced after 7 days, as shown by our finding that there was no statistically significant difference in outcomes between the early and delayed reduction group. Therefore, it might be better to perform reduction actively, even if a physician encounters pediatric patients with nasal bone fractures with over 7 days elapsed since the injury. Even if 2ŌĆō3 weeks have passed, reduction might still yield advantageous results compared to corrective rhinoplasty in terms of the future risk of nasal deformity.

Manipulation of the septum is another challenge in pediatric nasal fracture patients, and septoplasty should be carefully performed to avoid injury to the growth center, which is very important for future nasal growth and development [18]. In our cases, septoplasty or manipulation of the septum was not done; instead, the procedures mainly focused on bony reduction.

The growth of the facial skeleton in pediatric patients could causeŌĆöeven in patients with minor nasal fracturesŌĆöa higher likelihood of long-term problems such as nasal deviation, a dorsal hump, or nasal obstruction [19,20]. Therefore, long-term follow-up will be necessary even if the immediate postoperative results are satisfactory.

The limitations of this study are the difficulty of generalizing the results due to the small sample size, the lack of long-term results, and the necessity for a further comparison of surgical outcomes between early and later childhood due to differences in developmental characteristics and the impact of growth spurts.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daegu Catholic University Medical Center (IRB No. CR-21- 027-L) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The informed consent was waived.

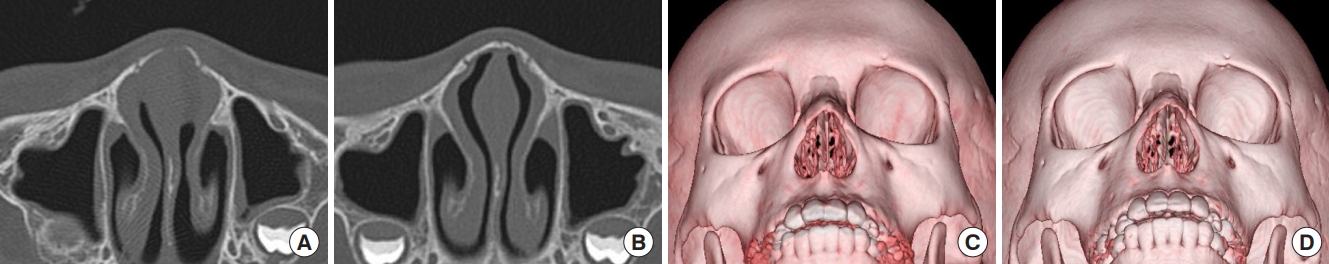

Fig.┬Ā1.

A 7-year-old boy had a nasal injury due to a steel structure (1.5 kg) falling onto his face. His parents were late to recognize that he had a nasal bone fracture. Closed reduction was performed 18 days after the initial trauma. (A) Preoperative axial computed tomography (CT) showed fractures on the left nasal wall and the caudal tip of the left frontal process with a slightly displaced segment. (B) Postoperative axial CT showed excellent outcomes without irregularity or displacement of the fracture segment. (C) Initial post-trauma three-dimensional CT image. (D) Postoperative three-dimensional image showing excellent results on the left nasal wall and frontal process.

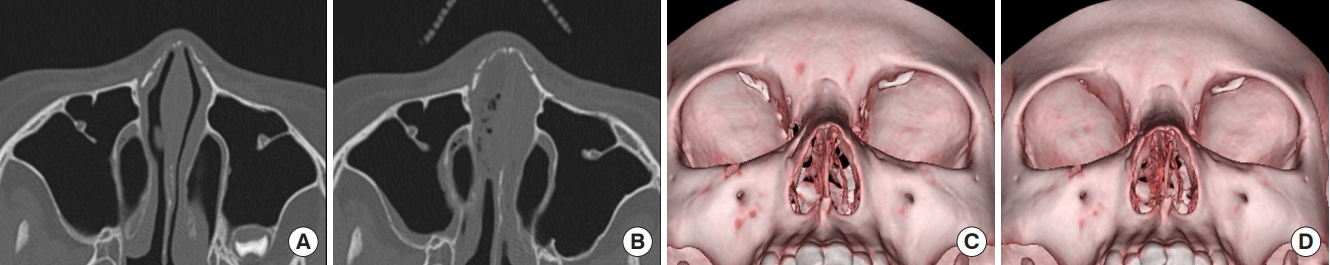

Fig.┬Ā2.

A 10-year-old girl had a nasal injury due to a traffic accident abroad. Due to delays entering the country, she had to undergo surgery on the 25th day after the initial trauma. The surgical results showed an excellent outcome. (A) Preoperative axial computed tomography (CT) showed moderate displacement on the tip and right nasal wall. (B) Postoperative axial CT showed an excellent outcome. (C) Initial post-trauma three-dimensional CT image. (D) Postoperative three-dimensional image showing excellent results on the nasal tip and right wall.

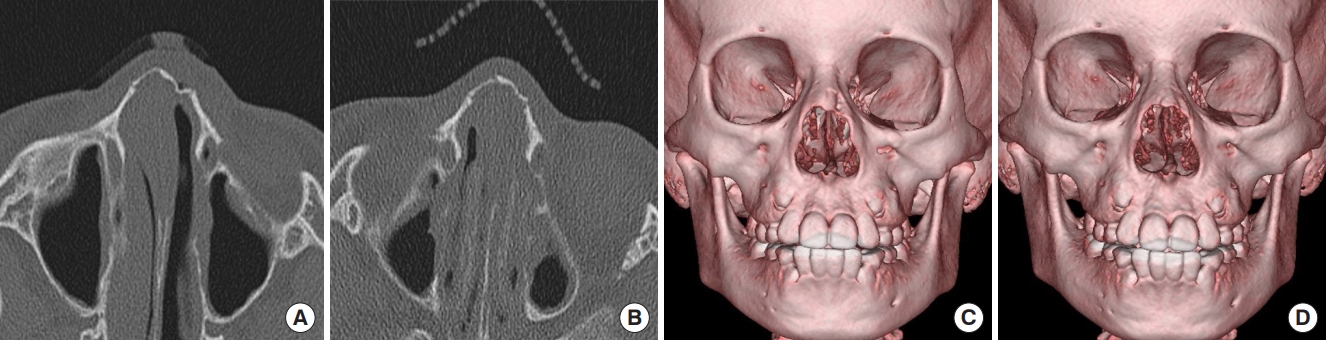

Fig.┬Ā3.

A 9-year-old boy had an accident in which his nose bumped onto the corner of his bed, and he underwent surgery 9 days after the initial trauma. Preoperative computed tomography (CT) images (A, C) showed a greenstick fracture on the tip and imprinted fractures on the left nasal wall. Postoperative CT images (B, D) demonstrated incomplete repositioning of the fracture segments after reduction.

Table┬Ā1.

Scores for postoperative outcomes based on CT scans

| Fracture condition on CT scans |

Score |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | Good | Fair | |

| Malalignment of fracture segment | None | (+) | (+) |

| One-segment bony irregularity | None | (+) | (+) |

| or | and | ||

| Bony displacement | None | (+) | (+) |

Table┬Ā2.

Characteristics of pediatric patients according to the interval from initial trauma to surgery

| Variable |

Interval from initial trauma to surgery |

|

|---|---|---|

| Within 7 days | Over 7 days | |

| No. of patients | 51 | 47 |

| Sex | ||

| ŌĆāMale | 34 | 32 |

| ŌĆāFemale | 17 | 15 |

| Mean age (range, yr) | 8.53 (2ŌĆō12) | 8.23 (3ŌĆō12) |

Table┬Ā3.

Postoperative outcomes according to the interval from initial trauma to surgery

| Variable |

Interval from initial trauma to surgery |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within 7 days | Over 7 days | ||

| No. of patients | 51 | 47 | |

| Type of fracture | |||

| ŌĆāFI | 21 | 16 | |

| ŌĆāLI | 24 | 27 | |

| ŌĆāFII | 3 | 2 | |

| ŌĆāLII | 3 | 2 | |

| Postoperative outcome (grade) | 0.937a) | ||

| ŌĆāExcellent | 42 | 39 | |

| ŌĆāGood | 9 | 8 | |

| ŌĆāFair | 0 | 0 | |

| Mean time elapsed from injury to surgery (range, day) | 5.67 (2ŌĆō7) | 10.21 (8ŌĆō25) | |

Table┬Ā4.

Postoperative outcomes based on the presence of a septal injury (n=98)

| Postoperative outcomes (grade) |

No. of patients (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With a septal injury | Without a septal injury | ||

| Excellent | 74 (89.2) | 7 (46.7) | < 0.01a) |

| Good | 9 (10.8) | 8 (53.3) | |

REFERENCES

1. Desrosiers AE 3rd, Thaller SR. Pediatric nasal fractures: evaluation and management. J Craniofac Surg 2011;22:1327-9.

2. Lee WT, Koltai PJ. Nasal deformity in neonates and young children. Pediatr Clin North Am 2003;50:459-67.

3. Yabe T, Tsuda T, Hirose S, Ozawa T. Comparison of pediatric and adult nasal fractures. J Craniofac Surg 2012;23:1364-6.

4. Ridder GJ, Boedeker CC, Fradis M, Schipper J. Technique and timing for closed reduction of isolated nasal fractures: a retrospective study. Ear Nose Throat J 2002;81:49-54.

5. Rohrich RJ, Adams WP Jr. Nasal fracture management: minimizing secondary nasal deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;106:266-73.

6. Yu H, Jeon M, Kim Y, Choi Y. Epidemiology of violence in pediatric and adolescent nasal fracture compared with adult nasal fracture: an 8-year study. Arch Craniofac Surg 2019;20:228-32.

7. Kim SH, Lee SH, Cho PD. Analysis of 809 facial bone fractures in a pediatric and adolescent population. Arch Plast Surg 2012;39:606-11.

8. Liu C, Legocki AT, Mader NS, Scott AR. Nasal fractures in children and adolescents: mechanisms of injury and efficacy of closed reduction. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2015;79:2238-42.

9. Stranc MF, Robertson GA. A classification of injuries of the nasal skeleton. Ann Plast Surg 1979;2:468-74.

10. Kang WK, Han DG, Kim SE, Lee YJ, Shim JS. Bone remodeling after conservative treatment of nasal bone fracture in pediatric patients. Arch Craniofac Surg 2020;21:166-70.

11. Kaban LB, Troulis MJ. Pediatric oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.

12. Perkins SW, Dayan SH, Sklarew EC, Hamilton M, Bussell GS. The incidence of sports-related facial trauma in children. Ear Nose Throat J 2000;79:632-8.

13. Vyas RM, Dickinson BP, Wasson KL, Roostaeian J, Bradley JP. Pediatric facial fractures: current national incidence, distribution, and health care resource use. J Craniofac Surg 2008;19:339-49.

14. Meier JD, Tollefson TT. Pediatric facial trauma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;16:555-61.

15. Wright RJ, Murakami CS, Ambro BT. Pediatric nasal injuries and management. Facial Plast Surg 2011;27:483-90.

16. Yilmaz MS, Guven M, Kayabasoglu G, Varli AF. Efficacy of closed reduction for nasal fractures in children. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013;51:e256-8.

18. Sarnat BG. Normal and abnormal growth at the nasoseptovomeral region. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1991;100:508-15.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 4 Crossref

- Scopus

- 3,412 View

- 79 Download

- Related articles in ACFS