|

|

- Search

| Arch Craniofac Surg > Volume 22(5); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

Prophylactic antibiotics are commonly used in craniofacial surgeries. Despite the low risk of surgical site infection after nasal surgery, a lack of consensus regarding the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in the closed reduction of nasal bone fractures has led to inappropriate prescribing patterns. Through this study, we aimed to investigate the status of prophylactic antibiotic use in closed reductions of nasal bone fractures in Korea.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort of Korea from 2005 to 2015. We analyzed the medical records of patients who underwent closed reduction of nasal bone fractures. The sex, age, region of residence, comorbidities, and socioeconomic variables of the patients were collected from the database. Factors that affect the prescription of perioperative antibiotics were evaluated using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

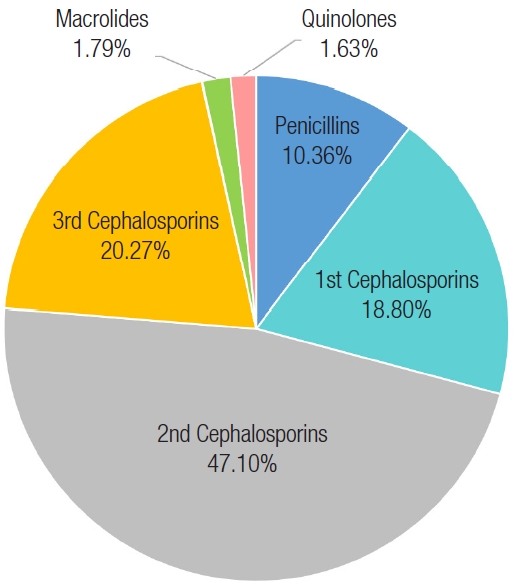

A total of 3,678 patients (mean± standard deviation of age, 28.7± 14.9 years; 2,850 men [77.5%]; 828 women [22.5%]) were included in this study. The rate of antibiotic prescription during the perioperative period was 51.4%. Approximately 68.8% of prescriptions were written for patients who had received general anesthesia. The odds of perioperative prophylactic antibiotic use were significantly higher in patients who received general anesthesia than who received local anesthesia (odds ratio, 1.59). No difference was found in terms of patient age and physician specialty. Second-generation cephalosporins were the most commonly prescribed antibiotic (45.3%), followed by third- and first-generation cephalosporins (20.3% and 18.8%, respectively). In contrast, lincomycin derivatives and aminoglycosides were not prescribed.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that there was a wide variety of perioperative antibiotic prescription patterns used in nasal bone surgeries. Evidence-based guidance regarding the prescribing of antimicrobial agents for the closed reduction of nasal bone fractures should be considered in future research.

The use of prophylactic antibiotics in the management of facial bone fractures is common. However, there is growing evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis is not necessary in clean or cleancontaminated facial bone surgeries [1,2]. Because there is no validated guide on the use of particular antibiotic regimens in facial bone surgeries, a wide variety of antibiotic prescription patterns currently exist [3-6].

Nasal bone fractures are the most common type of facial bone fractures; they account for approximately 40% of all facial bone injuries [7,8]. Simple closed reduction is generally performed for this type of fracture management, which involves the alignment of broken bones without incisions [9-12]. Although this non-incisional technique is considered a clean surgical procedure wherein antibiotic prophylaxis is not routinely recommended, many craniofacial surgeons still prescribe prophylactic antibiotics [6,13].

The incidence of surgical site infections in nasal surgeries is extremely rare [12,14,15]; however, mucosal barrier violation and intranasal packing during surgery may lead to infectious complications as a result of bacteremia (e.g., toxic shock syndrome, endocarditis, and meningitis) [12-15]. Hence, the benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis may outweigh its potential deleterious effects, including allergic reactions, increased medical costs, and the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Therefore, it can be argued that antibiotics should be prescribed to otherwise healthy individuals who undergo closed reduction of nasal bone fractures.

In Korea, the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) program has provided health care for more than 97% of the population since the 1980s [16]. The National Sample Cohort (NSC) was constructed by sampling approximately 2% (1,000,000 people) from the NHIS population. The NSC provides data including the general characteristics of patients, their medical records, and their socioeconomic variables [17].

This study was undertaken to identify trends in the prescription of perioperative antibiotics to patients who underwent closed reduction of nasal bone fractures in Korea using data from the NHIS-NSC. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that have assessed antibiotic use during the repair of nasal bone fractures using information from a nationwide cohort database.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using information from the NHIS-NSC. Patients who underwent closed reduction of nasal bone fractures during the period of January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2015 were included. Using electronic data interchange (code, N033), the following data were collected for the analysis of patient characteristics: sex, age, region of residence, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension), and socioeconomic variables (e.g., area of residence, household income). Data regarding the surgery performed, i.e., the type of medical institution where the procedure took place, type of anesthesia used, and the particular department of surgery in charge of the case, were also collected. In line with medical law in Korea, medical institutions were classified according to capacity or number of specialties: clinics (<30 beds), hospitals (30–99 beds), and general hospitals (≥100 beds, 6–9 specialties). Antimicrobial agents were classified as penicillin with β-lactamase inhibitors, cephalosporins (first to fourth generation), macrolides, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, lincomycin derivatives, tetracyclines, and glycopeptides. Information concerning the use of perioperative antibiotics on the day of surgery was collected. Patients who had been hospitalized for more than 7 days or who underwent simultaneous surgeries for other conditions were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital (IRB No. NHIMC 2021-03-008).

For data analysis, we used the chi-square test to analyze patient demographic differences based on the type of antibiotic prescription used. To determine factors that were independently associated with antibiotic prescription patterns, we performed multiple logistic regression (MLR) analysis to calculate the odds ratio of using and not using perioperative antibiotics. The MLR analysis included the following independent factors: age, sex, household income, region of residence, type of medical institution in which the surgery was performed, surgery department in charge, type of anesthesia used, and comorbidities. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All data were analyzed using SAS software, version 7.13 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Based on the NHIS database, 5,357 patients underwent closed reduction of nasal bone fractures between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2015. After exclusion of patients who were hospitalized for more than 7 days (n=1,282) and those who underwent simultaneous operations for other conditions (n=397), a total of 3,678 patients (mean±standard deviation age, 28.7±14.9 years; 2,850 men [77.5%]; 828 women [22.5%]) were included in the study. There was no significant difference in antibiotic administration rates based on patient age. Further, a total of 1,890 patients (51.4%) received perioperative prophylactic antibiotics (Table 1). The most commonly used antibiotic agents were second-generation cephalosporins (47.1%), followed by third- and first-generation cephalosporins (20.3% and 18.8%, respectively). No patients were prescribed lincomycin derivatives or aminoglycosides (Fig. 1). Results of the chisquare test showed that perioperative antibiotic prescription rates varied depending on the region of patient residence or type of medical institution; however, no significant difference was found. Plastic surgeons accounted for 1,442 of 1,891 physicians (61.6%) who prescribed antibiotics. Analysis of the data using MLR showed no significant difference in perioperative antibiotic prescription rates among the various physician specialties. Approximately 1,601 of 1,891 prescriptions (68.8%) were attributed to patients who received general anesthesia. Through MLR analysis, the odds of using perioperative prophylactic antibiotics were found to be significantly higher in patients who received general anesthesia (odds ratio, 1.59; p<0.001) versus those who received local anesthesia (Table 2).

Acknowledging the need for caution when prescribing antibiotics, our retrospective cohort study aimed to determine the current trends in perioperative antibiotic use during surgery for nasal bone fractures. We found that approximately one-half of the surgeons evaluated used perioperative prophylactic antibiotics when performing the closed reduction technique in the repair of nasal bone fractures. Growing evidence shows that antibiotic prophylaxis is not routinely recommended in uncomplicated facial bone surgery [1-3]. Coupling this with nationwide efforts to reduce antibiotic resistance, the continued use of perioperative antibiotics in patients who undergo closed reduction of nasal bone fractures is questionable.

In this study, we found that patients who received general anesthesia during surgery had higher rates of perioperative antibiotic prescription. This may be attributed to the requirement of intravenous access for the administration of general anesthesia. Additionally, plastic surgeons accounted for 1,165 of 1,891 physicians (61.6%) who prescribed antibiotics; however, MLR analysis revealed no significant differences in the rates of perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis between the particular surgical departments in charge of patient care.

Toxic shock syndrome is a life-threatening condition mainly caused by staphylococcal or streptococcal species. Because these bacteria are part of the normal flora of the nasal mucosa, prophylactic antibiotics may be prescribed by surgeons to prevent this serious complication [6,15]. First-generation cephalosporins are the most effective against Gram-positive bacteria compared with the other generations; as a result, cefazolin is the most recommended antibiotic of that class for head and neck procedures. Cefuroxime, a second-generation cephalosporin, and ampicillin-sulbactam, a β-lactamase inhibitor, are also recommended for surgical prophylaxis in clean-contaminated head and neck procedures [18-20]. However, our results show that second-generation cephalosporins were the most prescribed antibiotic agents (47.1%), followed by third-generation, and then first-generation cephalosporins. Although clindamycin and vancomycin are recommended as alternatives in patients with a β-lactam allergy, neither lincomycin derivatives nor glycopeptides were prescribed in our study population [18-20]. These results suggest that there may have been inappropriate use of prophylactic antibiotics, regardless of the current consensus on antibiotic prophylaxis. Given these data, there is an urgent need to produce specific guidelines on the antibiotic regimens used in craniofacial surgery.

The strength of this study was its use of a nationwide database to reveal trends in perioperative antibiotic prescription patterns in craniofacial surgeries in Korea. However, the use of the NHIS-NSC database had some limitations. First, it was unclear whether the antibiotic agents were prescribed as prophylaxis for closed reduction of the nasal bone; it is possible that the patients were given antibiotics for other reasons. We attempted to account for this by excluding patients who were admitted for more than 7 days and those who underwent simultaneous surgical procedures, as there was a high likelihood that antibiotics were prescribed to prevent complications from other conditions. Second, we did not have sufficient information on the other medical conditions that may have warranted therapeutic antibiotic prescription, such as immunosuppression, neutropenia, and malnourishment. In addition, we could not analyze the timing of antibiotic administration, i.e., whether the antibiotics were used before or after surgery, or the duration of regimen. In most cases of nasal surgery, prolonged prophylaxis after the operation has no benefits, even if the use of prophylactic antibiotics may be indicated [6]. Third, according to the chi-square test, no significant differences in perioperative antibiotic prescription rates were found between patient comorbidities (i.e., diabetes, hypertension); however, MLR analysis revealed that the odds of perioperative antibiotic prescription were significantly higher in patients without hypertension (odds ratio, 1.75), despite only 262 of 3,678 patients (7%) being diagnosed with hypertension. Thus, further studies involving a larger population are required to establish the association between comorbidities and antibiotic prescription rates.

In this retrospective cohort study, we explored the use of prophylactic antibiotics during surgery for nasal bone fractures. The results of our study revealed a wide variety of perioperative antibiotic prescription patterns used in nasal bone surgeries. Evidence-based guidance regarding the prescribing of antimicrobial agents for the closed reduction of nasal bone fractures should be considered in future research, as there is a need for a professional consensus and clear prescription guidelines in the area of craniofacial surgery.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital (IRB No. NHIMC 2021-03-008) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The informed consent was waived because of the analysis used anonymous clinical data.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Seum Chung. Data curation: Ji Hyuk Jung. Funding acquisition: Yeo Reum Jeon. Methodology: Joon Ho Song. Writing - original draft: Yeo Reum Jeon. Writing - review & editing: Yeo Reum Jeon, Seum Chung. Investigation: Ji Hyuk Jung, Joon Ho Song. Supervision: Seum Chung.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Characteristics | Overall (n=3,678) |

Perioperative antibiotics |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=1,787) | Yes (n=1,891) | ||||

| Sex | Male | 2,850 (77.5) | 1,393 (78.0) | 1,456 (77.0) | 0.49 |

| Female | 828 (22.5) | 394 (22.0) | 435 (23.0) | ||

| Age (yr) | ≤ 18 | 1,233 (33.5) | 616 (34.5) | 617 (32.6) | 0.58 |

| 19–30 | 1,020 (27.7) | 486 (27.2) | 534 (28.2) | ||

| 31–40 | 566 (15.4) | 262 (14.7) | 304 (16.1) | ||

| 41–50 | 483 (13.1) | 229 (12.8) | 254 (13.4) | ||

| 51–60 | 251 (6.8) | 126 (7.1) | 125 (6.6) | ||

| 61–70 | 88 (2.4) | 48 (2.7) | 40 (2.1) | ||

| ≥ 71 | 37 (1.0) | 20 (1.1) | 17 (0.9) | ||

| Household income | Low | 181 (4.9) | 94 (5.3) | 87 (4.6) | 0.26 |

| Medium | 1,093 (29.7) | 547 (30.6) | 546 (28.9) | ||

| Medium-high | 1,396 (38.0) | 651 (36.4) | 745 (39.4) | ||

| High | 1,008 (27.4) | 495 (27.7) | 513 (27.1) | ||

| District | Seoul | 774 (21.0) | 340 (19.0) | 434 (23.0) | < 0.001a) |

| Metropolitan city | 930 (25.3) | 510 (28.5) | 420 (22.2) | ||

| Elsewhere | 1,974 (53.7) | 937 (52.4) | 1,037 (54.8) | ||

| Type of institution | General hospital | 1,081 (29.4) | 303 (17.0) | 778 (41.1) | < 0.001a) |

| Hospital | 1,141 (31.0) | 390 (21.8) | 751 (39.7) | ||

| Clinics | 1,456 (39.6) | 1,094 (61.2) | 362 (19.1) | ||

| Type of anesthesia | General | 1,492 (40.6) | 191 (10.7) | 1,301 (68.8) | < 0.001a) |

| Local | 2,186 (59.4) | 1,596 (89.3) | 590 (31.2) | ||

| Specialty | Plastic surgery | 1,442 (39.2) | 277 (15.5) | 1,165 (61.6) | < 0.001a) |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 1,417 (38.5) | 928 (51.9) | 489 (25.9) | ||

| Other | 819 (22.3) | 582 (32.6) | 237 (12.5) | ||

| Diabetes | Yes | 174 (4.7) | 94 (5.3) | 80 (4.2) | 0.14 |

| Hypertension | Yes | 262 (7.1) | 125 (7.0) | 137 (7.2) | 0.77 |

Table 2.

Odds ratio of perioperative antibiotic prescription

| Characteristics | Odds ratios | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1.07 | 0.60 |

| Female | 1.00 | ||

| Age (yr) | ≤ 18 | 1.00 | |

| 19−30 | 1.38 | 0.28 | |

| 31−40 | 1.46 | 0.51 | |

| 41−50 | 1.35 | 0.27 | |

| 51−60 | 1.53 | 0.78 | |

| 61−70 | 2.16 | 0.37 | |

| ≥ 71 | 3.18 | 0.15 | |

| Household income | Low | 0.77 | 0.38 |

| Medium | 1.06 | 0.14 | |

| Medium-high | 0.86 | 0.52 | |

| High | 1.00 | ||

| Region | Seoul | 1.00 | |

| Metropolitan city | 1.05 | 0.89 | |

| Elsewhere | 1.06 | 0.77 | |

| Type of institution | General hospital | 1.11 | 0.76 |

| Hospital | 1.15 | 0.51 | |

| Clinics | 1.00 | ||

| Type of anesthesia | General | 1.59 | < 0.001a) |

| Local | 1.00 | ||

| Specialty | Plastic surgery | 1.00 | |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 0.98 | 0.61 | |

| Other | 1.12 | 0.56 | |

| Diabetes | Yes | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| No | 0.98 | ||

| Hypertension | Yes | 1.00 | 0.02a) |

| No | 1.75 |

REFERENCES

1. Adalarasan S, Mohan A, Pasupathy S. Prophylactic antibiotics in maxillofacial fractures: a requisite? J Craniofac Surg 2010;21:1009-11.

2. Fay A, Nallasamy N, Allen RC, Bernardini FP, Bilyk JR, Cockerham K, et al. Perioperative prophylactic antibiotics in 1,250 orbital surgeries. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2020;36:385-9.

3. Brooke SM, Goyal N, Michelotti BF, Guedez HM, Fedok FG, Mackay DR, et al. A multidisciplinary evaluation of prescribing practices for prophylactic antibiotics in operative and nonoperative facial fractures. J Craniofac Surg 2015;26:2299-303.

4. Habib AM, Wong AD, Schreiner GC, Satti KF, Riblet NB, Johnson HA, et al. Postoperative prophylactic antibiotics for facial fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 2019;129:82-95.

5. Knepil GJ, Loukota RA. Outcomes of prophylactic antibiotics following surgery for zygomatic bone fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2010;38:131-3.

6. Jang N, Shin HW. Are postoperative prophylactic antibiotics in closed reduction of nasal bone fracture valuable?: prospective study of 30 cases. Arch Craniofac Surg 2019;20:89-93.

7. Atighechi S, Karimi G. Serial nasal bone reduction: a new approach to the management of nasal bone fracture. J Craniofac Surg 2009;20:49-52.

8. Hwang K, You SH. Analysis of facial bone fractures: an 11-year study of 2,094 patients. Indian J Plast Surg 2010;43:42-8.

9. Han DG. Considerations for nasal bone fractures: preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative. Arch Craniofac Surg 2020;21:3-6.

10. Park YJ, Ryu WS, Kwon GH, Lee KS. The clinical usefulness of closed reduction of nasal bone using only a periosteal elevator with a rubber band. Arch Craniofac Surg 2019;20:284-8.

11. Lee YJ, Lee KT, Pyon JK. Finger reduction of nasal bone fracture under local anesthesia: outcomes and patient reported satisfaction. Arch Craniofac Surg 2019;20:24-30.

12. Park HK, Lee JY, Song JM, Kim TS, Shin SH. The retrospective study of closed reduction of nasal bone fracture. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;36:266-72.

13. Herman TF, Bordoni B. Wound classification. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

14. Lee JW, Kim YJ, Kim H, Nam SH, Shin BM, Choi YW. Nasal carriage of 200 patients with nasal bone fracture in Korea. Arch Plast Surg 2013;40:536-41.

15. Makitie A, Aaltonen LM, Hytonen M, Malmberg H. Postoperative infection following nasal septoplasty. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2000;543:165-6.

16. Ryu DR. Introduction to the medical research using national health insurance claims database. Ewha Med J 2017;40:66-70.

17. Lee J, Lee JS, Park SH, Shin SA, Kim K. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort(NHIS-NSC), South Korea. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:e15.

18. Ottoline AC, Tomita S, Marques Mda P, Felix F, Ferraiolo PN, Laurindo RS. Antibiotic prophylaxis in otolaryngologic surgery. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013;17:85-91.

19. World Health Organization (WHO). Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- Scopus

- 2,996 View

- 68 Download

- Related articles in ACFS

-

Antibiotic use in nasal bone fracture: a single-center retrospective study2021 December;22(6)