Abbreviations:

full thickness skin graft

;

orbicularis oculi musculocutaneous

;

split thickness skin graft

.

INTRODUCTION

Facial skin structure varies based on creases, wrinkles, and skin thickness; hence, satisfactory cosmetic and functional reconstruction of large defects in the facial area poses a challenge even to experienced plastic surgeons [

1]. Facial reconstruction can be performed using primary closure, local flap, distant flap, or free flap. It depends on various factors, such as the size and location of the defects, and the condition of adjacent tissues. However, skin grafting has both functional and cosmetic limitations; it can result in postoperative deformation due to contraction, and color mismatch with the surrounding skin [

2]. Free-flap reconstruction can be performed for large defects with favorable functional results. Nonetheless, it achieves low patient satisfaction because of cosmetic reasons owing to scarring, and it is a burdening reconstruction procedure given that most patients with skin cancer are older patients [

3,

4].

Forehead flaps are natural and durable axial flaps that are supplied with blood by the supraorbital or supratrochlear blood vessels. Moreover, they are suitable donor flaps for the facial skin, as the color and texture match the facial skin [

5,

6]. In addition, regarding donor site scar formation and deformation, previous studies have reported satisfactory results for forehead flap reconstruction with primary closure [

7]. Considering these features, it is possible to cover a large defect on the midface by designing various shapes on the forehead as necessary; however, if a large defect is reconstructed with only the forehead flap, it is impossible to cover a large defect on the forehead by primary closure. Eventually, a scar that is not cosmetically satisfactory in the forehead is generated, causing the surgeon to hesitate.

Skin thicknesses and folds vary; hence, bulging deformities may occur after single forehead flap application at locations with thin skin, such as the eyelids and the boundary between the nose and cheeks [

8]. Considering these problems, if satisfactory reconstruction cannot be achieved with only one forehead flap, the aforementioned weakness can be compensated using other reconstruction techniques simultaneously. Therefore, a combination of procedures can completely cover the defect while reducing the width of the forehead flap and aiding primary closure of the donor site. We decided to introduce our method because we have obtained satisfactory results by combining various procedures for covering large defects in the facial area.

METHODS

Reconstruction with forehead flaps was performed in 63 patients between February 2005 and June 2020 at our institution. Out of 63 patients, 22 underwent a combination of forehead flap reconstruction and another procedure. These 22 patients were retrospectively evaluated using chart reviews and questionnaires. This study was approved by the institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from all patients and caregivers.

The selected patients included 10 men and 12 women, with an average age of 68 years (range, 45ŌĆō91 years). The diagnosis was basal cell carcinoma (BCC) in 19 patients and squamous cell carcinoma in three patients, with the occurrence of soft tissue defects following Mohs microscopic surgery (MMS). Twenty patients had primary cancerous lesions, whereas two patients had recurrence following treatment for skin cancer. Additional procedures included nasolabial V-Y advancement flap, orbicularis oculi musculocutaneous (OOMC) V-Y advancement flap, local advancement flap, grafting, and simultaneous application of two techniques. The follow-up period for the 22 selected patients ranged from 6 to 180 months. Their mean follow-up period was 28 months.

Major postoperative complications including flap loss, and minor complications such as partial necrosis, hematoma, infection, and dehiscence, were analyzed through chart reviews. Patient satisfaction with the surgical results was evaluated using questionnaires. This survey was conducted to confirm the satisfaction judged by the patient. Patient satisfaction questionnaire survey was assessed based on contour, color matching, and scar formation. Responses were assessed on a 5-point scale for each item (1= very dissatisfied, 2= dissatisfied, 3= fair; 4= satisfied, 5= very satisfied) [

9,

10]. Answers were provided by the patients themselves in 18 cases; however, in three cases, evaluation was performed based on the responses provided by their closest caregivers because of the inability of the patients to communicate. Postoperative evaluation was performed after 6 months at the earliest.

RESULTS

Among 63 patients who underwent reconstructive surgery using forehead flaps, 22 patients (approximately 35%) underwent a combination of procedures. Reconstruction with median and paramedian forehead flaps was performed in 15 and 7 patients, respectively. Additional procedures using local flapsŌĆönasolabial V-Y advancing flap, local advancing flap, and OOMC V-Y advancing flapŌĆöwere performed in nine, three, and two patients, respectively. Five patients underwent grafting, which included split-thickness skin grafting in two patients and separate full-thickness skin grafting, composite grafting, and mucosal grafting in one patient each. The remaining three patients underwent a combination of the forehead flap and two different additional techniques. The combination of procedures performed in these three patients was as follows: OOMC V-Y advancement flap with nasolabial V-Y advancement flap; two OOMC V-Y advancement flaps from the upper and lower eyelids; and right nasolabial transposition flap and left nasolabial rotation advancement flap (

Table 1).

Postoperatively, major complications (e.g., flap loss) and minor complications (e.g., partial necrosis, hematoma, infection, dehiscence) were absent in all the patients who underwent the procedures. Three patients complained of nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea after surgery; among them, symptoms of nasal obstruction in one patient improved after revision surgery. The causative cancer (BCC) recurred in two patients in whom reconstruction was performed using a combination of forehead flaps and grafting.

Postoperative satisfaction was evaluated in 18 patients. The scores, represented as mean┬▒ standard deviation, were 3.55┬▒1.19 for contour, 3.94┬▒0.99 for color match, and 3.66┬▒ 1.18 for scar formation (

Table 2). The total score obtained was 11.17┬▒2.83 out of 15. The total scores observed with different techniques were as follows: nasolabial V-Y advancement flap: 11.25┬▒3.01, local advancement flap: 12.67 ┬▒ 1.53, OOMC V-Y advancement flap: 13.00 ┬▒ 1.41, and grafting: 10.50 ┬▒ 0.70. Furthermore, patients who underwent a combination of two different techniques reported a total score of 8.33┬▒ 3.78 (

Table 3).

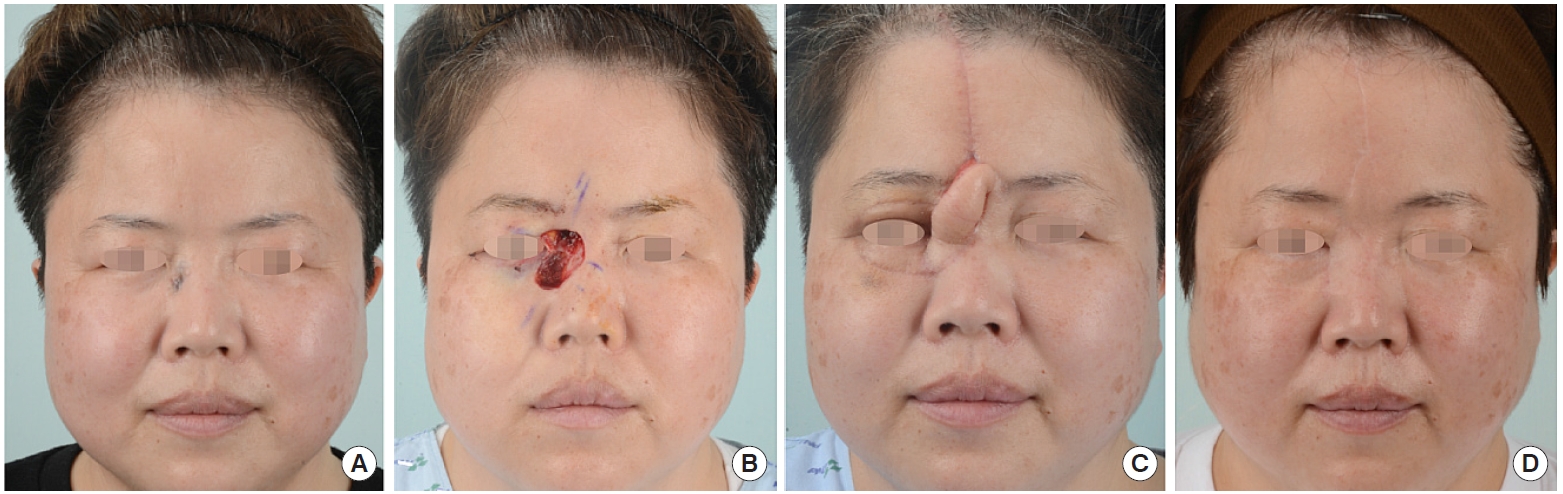

Whereas the eyelid skin is thin, the skin covering the nose and the cheeks is relatively thick. If a defect involving the eyelids as shown in

Fig. 1 would be reconstructed with a forehead flap only, a bulging deformity may occur. Moreover, the large width of the defect (3 cm), would make primary closure difficult, if the forehead flap would be elevated without width reduction. As shown in

Fig. 1, OOMC flaps were used on the upper and lower eyelids to cover the thin skin eyelid and reduce the width of the defect. Subsequently, the remaining defect was reconstructed with a forehead flap.

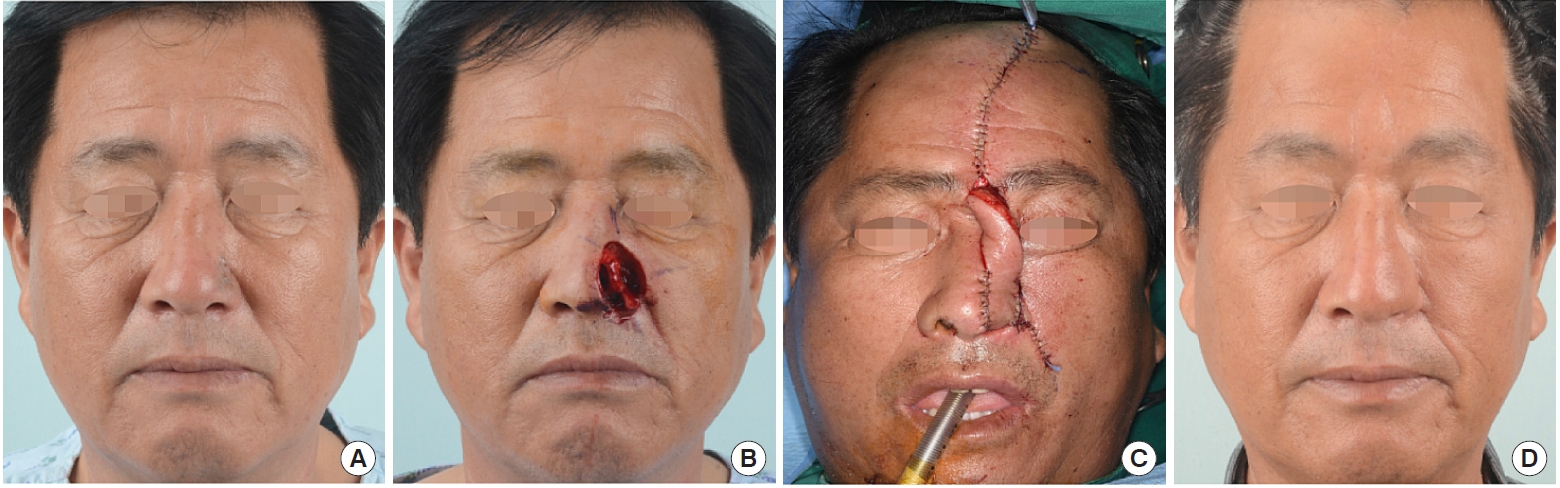

When a major defect occurs in the nose, the forehead flap can be an excellent reconstruction tool. However, if the defect involves both the nose and a cheek, as shown in

Fig. 2, it is difficult to reproduce an alar groove with a forehead flap only. Therefore, the nose was reconstructed with a forehead flap after using a cheek flap for delineation of the alar groove (

Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

A considerable number of the literature available on forehead flaps were based on concepts, techniques, and applications [

11]; to the best of our knowledge, no paper has reported the results of reconstructive surgery for large defects using a combination of forehead flaps and various techniques.

Forehead flaps are versatile and reliable and can be utilized through various approaches; hence, reconstruction of large defects has been performed using forehead flaps alone, such as total nasal reconstruction with forehead flaps. However, an attempt to cover a large defect with only the forehead flap will inevitably result in a large scar on the donor site [

8,

12,

13]. To reconstruct the donor site with such a large defect, it can be left to heal secondarily or a skin graft can be performed. Considering this, the drawback of having a large scar on the forehead is unavoidable. The results at both donor and recipient sites were considered important. Therefore, we aimed to design the forehead flap with primary closure in mind.

Plastic surgeons should attempt to achieve a delicate balance between the application of various flap techniques for reconstruction and prevention of potential morbidity to the donor site [

4]. If large defects are reconstructed with a single flap, increased tension would arise during closure of the donor site; hence, wound dehiscence or hypertrophic scar formation may occur. If the defects are not closed, contractures or large scar formations may occur due to secondary healing or use of skin grafts [

14]. Santos Stahl et al. [

15] and Little et al. [

16] reported an approximately 5% increase in the rate of skin necrosis after a forehead flap. Skin necrosis was however not noted in any of our patients. Primary closure was possible for all donor sites. The reason for this difference is thought to be that the forehead flap was not excessively used by reducing the size of the defect with additional procedures. Taking a lot of tissue from the donor site and reconstructing it on the defect site can be a satisfactory result for the recipient site. However, the surgeon must keep in mind that damage will obviously occur to the donor site [

17].

In cases with large defects that cannot be sufficiently reconstructed using local flaps, a skin graft or free flap may be used. However, skin grafts result in a typical patchy appearance because of the color mismatch and contour differences; thus, it produces a cosmetically unsatisfactory outcome [

2,

18,

19]. In addition, it has a low functional satisfaction due to loss of elasticity and graft retraction. Reconstruction with free flaps is a promising technique for deep and wide defects. However, it requires considerable technical expertise, and it is considered time-consuming even by experienced surgeons [

4]. Patients with skin cancer are generally of older age; thus, special attention must be paid to their general conditions [

20]. The occurrence of contour changes, scar formations, color mismatches, and deformations following surgery are the main disadvantages of using free flaps [

3]. Both skin grafting and the free flap method require long-term dressing; hence, they require a long hospital stay, which is another disadvantage.

Statistical analysis was not possible due to the insufficient number of patients; nevertheless, the lowest score was recorded when two different techniques were used. In this case, ŌĆ£forehead flap+╬▒ŌĆØ was not considered to be sufficient; hence, ŌĆ£forehead flap+╬▒+╬▓ŌĆØ was used. Among the scoring categories, it received a relatively low score with respect to contour. It is thought that the cause of this result is that the size of the defect is large enough to require ŌĆ£+╬▓.ŌĆØ Patients with low scores generally complained of discomfort due to bulging deformities. It is disproved by the fact that contour shows the lowest value among the three categories. Patients who complained like this recommended revision operation 6 months after surgery.

A study limitation is that we did not compare the operation with the forehead flap alone. In our hospital, the forehead flap was only used when it was determined that primary closure of the donor site was possible. In the end, the forehead flap was used alone only when the defect size was small. The size of the defect determines if only a forehead flap or a combination of a forehead flap and other procedures is used. Considering this size difference, comparing the two groups is inevitably biased.

To reconstruct the defect that occurred after MMS due to skin cancer, the surgeon should be able to use various reconstruction methods. Since the skin of the face has various creases, wrinkles, and skin thicknesses, it is necessary to cover it using various flaps around it to increase the satisfaction after surgery. It is difficult to express the diversity of thickness and boundaries with only one flap for a large defect. Therefore, we used various flaps for reconstruction and achieved satisfactory outcomes.

In this study, reconstructive surgery using a combination of forehead flaps and other procedures was performed for large facial defects after MMS in patients with skin cancer because reconstruction with forehead flaps alone was considered to be challenging. The operator can obtain satisfactory cosmetic and functional results by learning various surgical methods and applying the combined technique for reconstruction of large facial defects.