Pseudoaneurysm of the superficial temporal artery after blunt trauma: case report and literature review

Article information

Abstract

An 88-year-old man presented with a left temporal pulsatile mass that developed after blunt trauma. Based on suspicion of hematoma, needle aspiration was performed with the removal of approximately 15 mL of blood. No evident improvement was noted, and active arterial bleeding was observed at the needle puncture site. Doppler ultrasonography revealed a “yin-yang” sign, and the mass was diagnosed as a pseudoaneurysm of the left superficial temporal artery. Under general anesthesia, the superficial temporal artery was ligated and the pseudoaneurysm was removed. Superficial temporal artery pseudoaneurysm is a rare facial tumor that generally occurs after blunt trauma. Due to its rarity, pseudoaneurysms are often misdiagnosed as hematoma. The treatment of choice is excision, although endovascular intervention is a potential treatment option. However, when a pseudoaneurysm is small, conservative treatment can be used.

INTRODUCTION

The development of a hematoma in the frontotemporal region is relatively common after blunt facial trauma. Most hematomas in the facial region respond to conservative treatment or needle aspiration with compressive dressing. However, in rare cases, the mass continues to grow with repeated recurrence even after aspiration, and such cases should be considered for the possibility of pseudoaneurysm. Pseudoaneurysm of the superficial temporal artery is usually caused by trauma and is rarely reported. These pseudoaneurysms exhibit progressive growth, and when left untreated, they can eventually lead to severe bleeding. Here, we report a case of pseudoaneurysm of the left superficial temporal artery after blunt facial trauma.

CASE REPORT

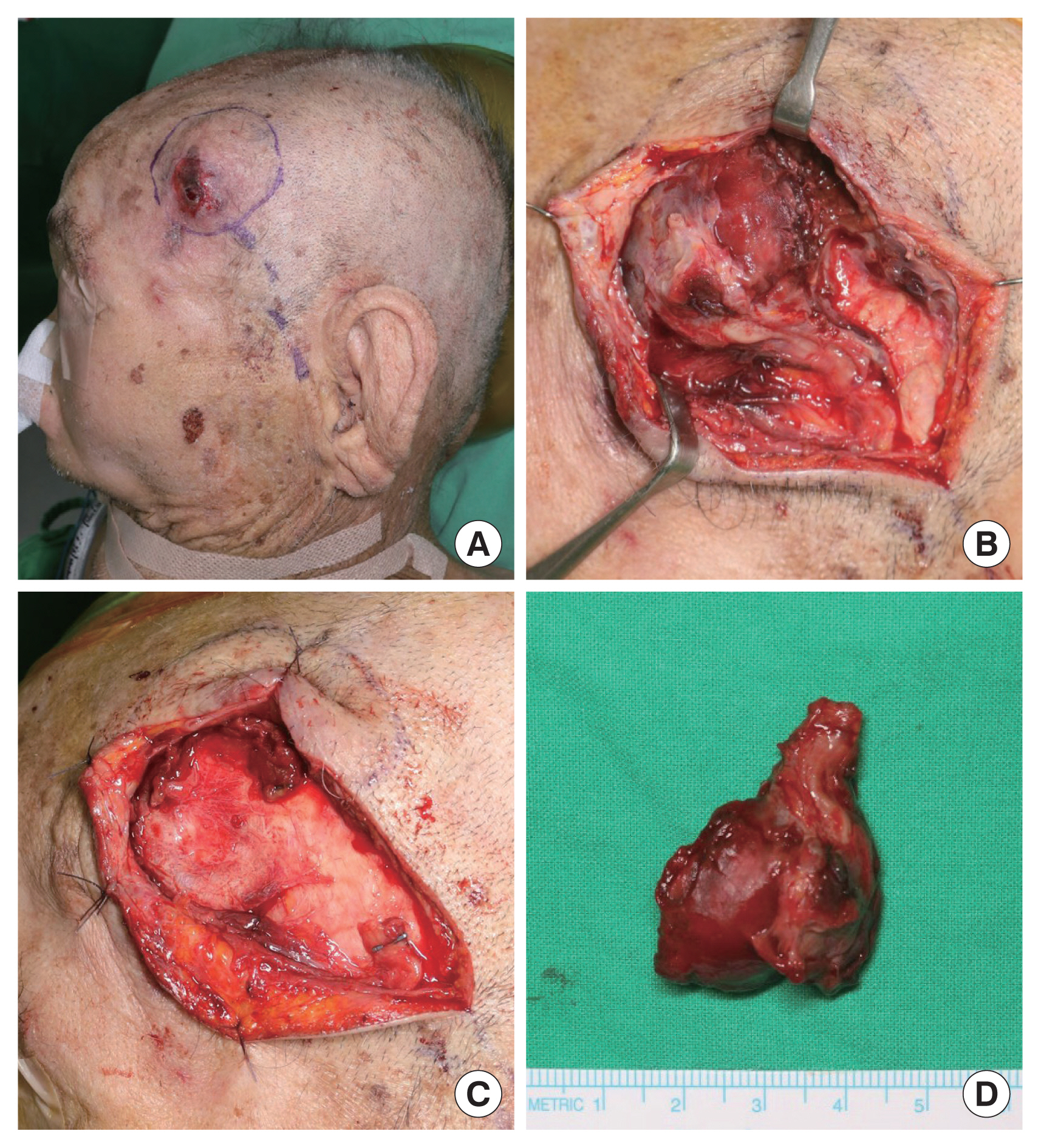

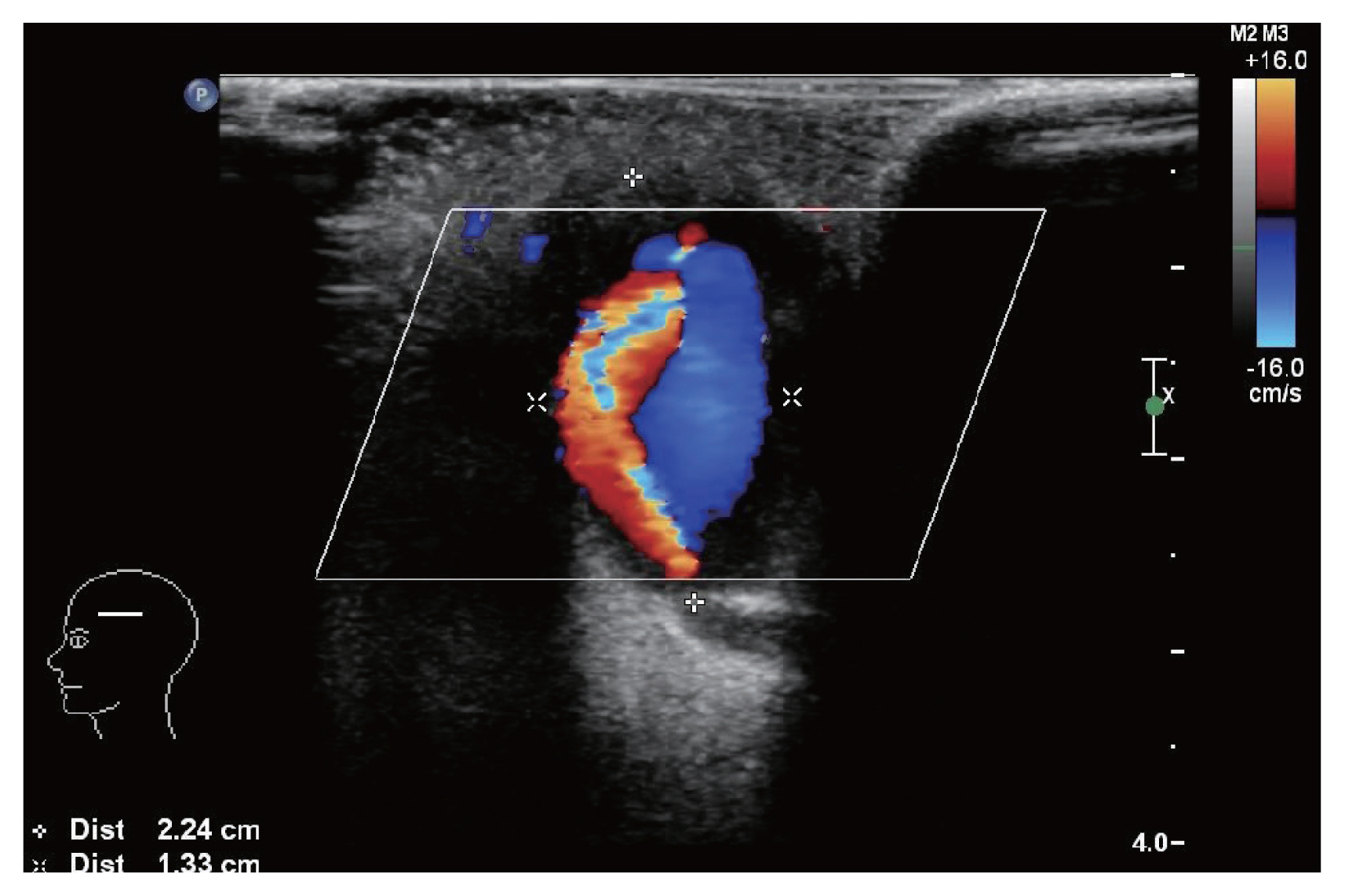

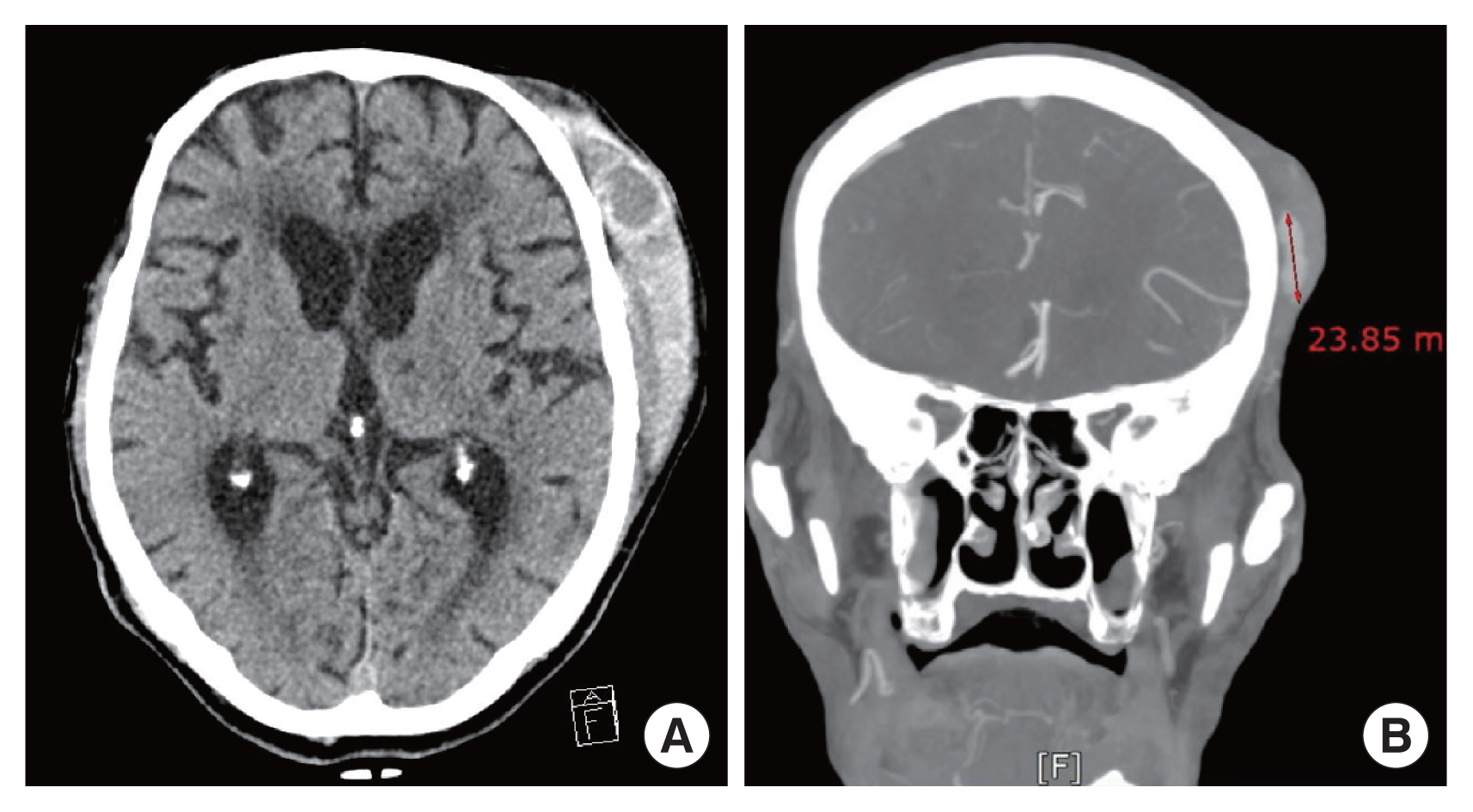

An 88-year-old man with high blood pressure and diabetes was presented to our emergency department after he had collapsed on the street. On the day before the accident, he had fallen and struck his head on the floor in his home; however, he had been conscious and shown no symptoms. Therefore, he had not sought medical evaluation. On presentation, he was in a stuporous state with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 12. Traumatic intracranial hemorrhage and left zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture were diagnosed based on the computer tomography (CT) findings. Additionally, a mass with a diameter of 1 cm was observed on the left temple with a suspicion of hematoma. Based on these findings, we decided to perform conservative treatment. The patient returned 1 week after the injury as the mass had increased in size. Based on the suspicion of hematoma, needle aspiration was performed with the removal of approximately 15 mL of blood. The size of the mass did not decrease, and active arterial bleeding was observed at the puncture site. Therefore, aspiration was stopped, and compression was performed. Three days later, the patient returned again for evaluation. On visual inspection, the mass had further increased in size, and the arterial pulse was palpable in the mass. Doppler ultrasonography revealed notable venous and arterial flow, and color Doppler imaging showed the taegeuk pattern (also known as the “yin-yang” sign), which is pathognomonic of pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 1). The size of the mass at this time was approximately 2.5×1.5×1.8 cm, as determined using CT angiography (Fig. 2). Exploration was performed under general anesthesia. A pseudoaneurysm was located in the region where the superficial temporal artery bifurcates into the frontal and parietal branches. Excision was performed after ligating the proximal and distal ends of the pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 3). Biopsy was used to confirm the diagnosis of pseudoaneurysm. The patient recovered well with an inconspicuous scar. No sign of recurrence was noted for 6 months after the operation.

Direct communication between the superficial temporal artery and turbulent flow observed using Doppler ultrasonography. The latter is known as the “yin-yang” sign and is pathognomonic of pseudoaneurysm.

(A) Axial and (B) coronal computed tomography showing approximately 2.5×1.5×1.8 cm-sized oval mass in the left frontotemporal region.

DISCUSSION

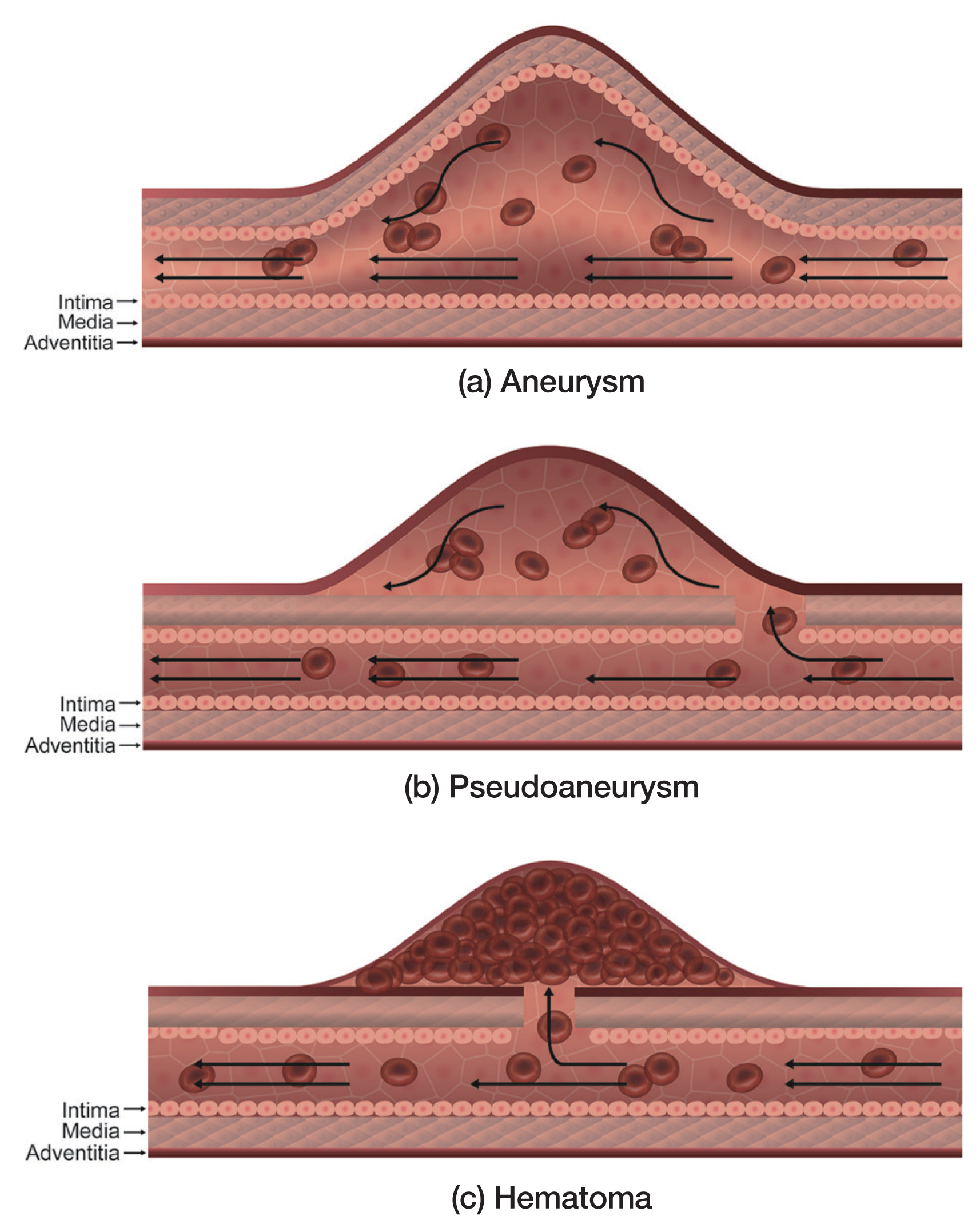

The terms pseudoaneurysm, false aneurysm, and pulsatile hematoma or communicating hematoma are synonymous [1]. In true aneurysms, the vessel wall is dilated to full thickness (Fig. 4, in part a), whereas in pseudoaneurysms, the blood vessels are dilated due to damage to one or more layers of the artery wall (Fig. 4, in part b). Hematoma development indicates damage to the blood vessel wall at full thickness and that there are several blood clots outside the vessel (Fig. 4, in part c). The pathogenesis of traumatic pseudoaneurysm is well established. Briefly, trauma damages a blood vessel and causes the rupture of the inner layer of the vessel wall. Blood pressure then causes the blood to fill this gap and form a cavity. Subsequently, a fibrous pseudocapsule is formed, which is known as a pseudoaneurysm [1,2].

The etiologies of true aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm differ. True aneurysms are usually caused by degenerative factors, whereas pseudoaneurysms are caused by trauma [1,2]. The causes of traumatic pseudoaneurysm include sports, traffic accidents, stab wounds, blunt injury, temporomandibular joint arthroplasty, hair transplantation, skin tumor excision, mandibular condylar fracture, or neurosurgical use of cranial halo fixation [1–4].

Suspicion is critical for the diagnosis of pseudoaneurysm; however, hematoma and pseudoaneurysms of the superficial temporal artery do not differ visually. The most characteristic feature of pseudoaneurysm of the superficial temporal artery is the presence of a pulsatile mass [1,2,4–6]. Notably, if the mass is punctured using a needle for aspiration, its size does not decrease even after aspiration. Moreover, active arterial bleeding occurs at the puncture site. These observations strongly indicate that a mass for which active arterial bleeding cannot be detected at the puncture site is a hematoma and not a pseudoaneurysm because the blood forms a clot outside the blood vessel. The presence of active arterial bleeding indicates that the entire mass was subjected to pressure, which implies that it is an aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm. In our case, active arterial bleeding was observed at the puncture site.

When a pseudoaneurysm is suspected, diagnostic tests, such as Doppler ultrasonography, CT angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, or conventional angiography, should be performed [7]. Doppler ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality [8] that reveals direct communication between the superficial temporal artery and turbulent flow, which is responsible for the yin-yang sign that is pathognomonic of pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 1) [6,8–10]. CT angiography can assess the patency and position of the main trunk and distal branches, including the transverse facial, frontal, and parietal branches of the superficial temporal artery [11]. Furthermore, CT angiography accurately depicts the true size of pseudoaneurysms along with the degree of thrombosis versus amount of luminal opacification [11]. Moreover, based on location, attenuation, and enhancement, CT angiography can identify pseudoaneurysms of the superficial temporal artery. We performed Doppler ultrasonography and CT angiography in this case. The yin-yang sign was observed using Doppler ultrasonography, which resulted in a diagnosis of pseudoaneurysm, and CT angiography revealed that the lesion was located in the area where the superficial temporal artery bifurcates into the frontal and parietal branches.

The goals of pseudoaneurysm treatment are to prevent rupture or hemorrhage, relieve pain, and obtain satisfactory cosmetic results. The most successful standard treatment is surgical ligation and resection [4], which involves the ligation of afferent and efferent vessels and excision of the pseudoaneurysm [1,4,5]. Ultrasound-guided thrombin injection and endovascular coil embolization are alternative treatment options [4,6,12, 13]. Small pseudoaneurysms can be treated conservatively through compression, although this approach is not recommended [5].

Kim et al. [4] suggested a treatment protocol for pseudoaneurysm of the superficial temporal artery. Pseudoaneurysms are classified based on the times elapsed after the onset as follows: acute (<3 weeks), subacute (3 weeks to 3 months), or chronic (>3 months). Emergency surgery should be performed in patients with an acute pseudoaneurysm and hemodynamic instability. If surgical removal is difficult, endovascular treatment can be performed. However, for cases in which a small pseudoaneurysm is hemodynamically stable, conservative treatment, such as compression, may be used. Subacute and chronic pseudoaneurysms can be treated surgically or via endovascular intervention based on the patient’s cosmetic preferences.

If left untreated, a pseudoaneurysm may rupture and can cause a life-threatening hemorrhage, although its incidence is low [14]. Hemostasis can be extremely challenging even using a surgical approach. Therefore, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential.

Abbreviation

CT

computer tomography

Notes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dongguk University Hospital (IRB No. 110757-202204-HR-03-02).

Patient consent

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of his images.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Inho Kang, Hea Kyeong Shin. Data curation: Inho Kang, Hea Kyeong Shin. Writing - original draft: Inho Kang. Writing - review & editing: Inho Kang, Young Woong Mo, Gyu Yong Jung, Hea Kyeong Shin. Supervision: Hea Kyeong Shin. Approval of the final manuscript: all authors.