INTRODUCTION

The nasal bone is the most common site of facial bone fractures, because the nose protrudes from the center of the face and the nasal bone is only protected by a thin layer of skin and fatty tissue [

1ŌĆō

8]. Numerous papers have been published about nasal bone fractures, primarily focusing on young adults and sometimes on pediatric patients. Therefore, these injuries in the elderly remain under-studied.

In Korea, the elderly population accounted for more than 14% of the total population in 2017, and this proportion is expected to exceed 20% by 2026 [

9,

10]. Population aging is, in fact, a global trend. Japan and Italy became aging societies in 2006, Germany in 2008, and Sweden and France did so in 2018 [

11]. However, the proportion of the elderly population in Korea doubled within only 17 years, transforming it from an aging society to an aged society at a pace that was unprecedented in human history [

12].

Some studies have reported that the epidemiology of nasal bone fractures changes with age. Therefore, this study investigated the epidemiology and patterns of nasal bone fractures in older adults, with a focus on identifying distinctive characteristics through a comparative analysis among different age groups. Based on our findings, we suggest ways of reducing the incidence and severity of fractures, by which we hope to improve the quality of life of the elderly.

METHODS

A retrospective study was conducted on a total of 2,321 nasal bone fracture patients who underwent surgery at our hospital over an 8-year period from January 2010 to December 2017. The epidemiology and patterns of nasal bone fractures were investigated based on patientsŌĆÖ medical records, radiographic findings, and computed tomography of the facial bone. The study also included patients who had a history of previous nasal bone fracture or augmentation rhinoplasty, as well as patients who concomitantly presented with other fractures, such as blowout or zygomaticomaxillary fractures. PatientsŌĆÖ age, sex, cause of injury, and fracture classification were analyzed. Patients were divided by age into four groups: preschoolers (0ŌĆō5 years), school-age children (6ŌĆō17 years), young and middle-aged adults (18ŌĆō64 years), and the elderly (Ōēź65 years). In each age group, we analyzed the distribution of sex, cause of injury, and fracture type. The causes of injury were classified into five categories: violence, fall or slip down, sports, road traffic accident (TA), and other causes (bumping into a falling object or unknown). The fracture types were analyzed separately in terms of the injury vector (frontal impact and lateral force) and plane of the fracture (planes 1, 2, and 3) through facial computed tomography according to the Stranc and Robertson classification [

13].

The Pearson chi-square test and Fisher exact test were used for pairwise comparisons of differences between the elderly and each other group. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) with the significance level set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

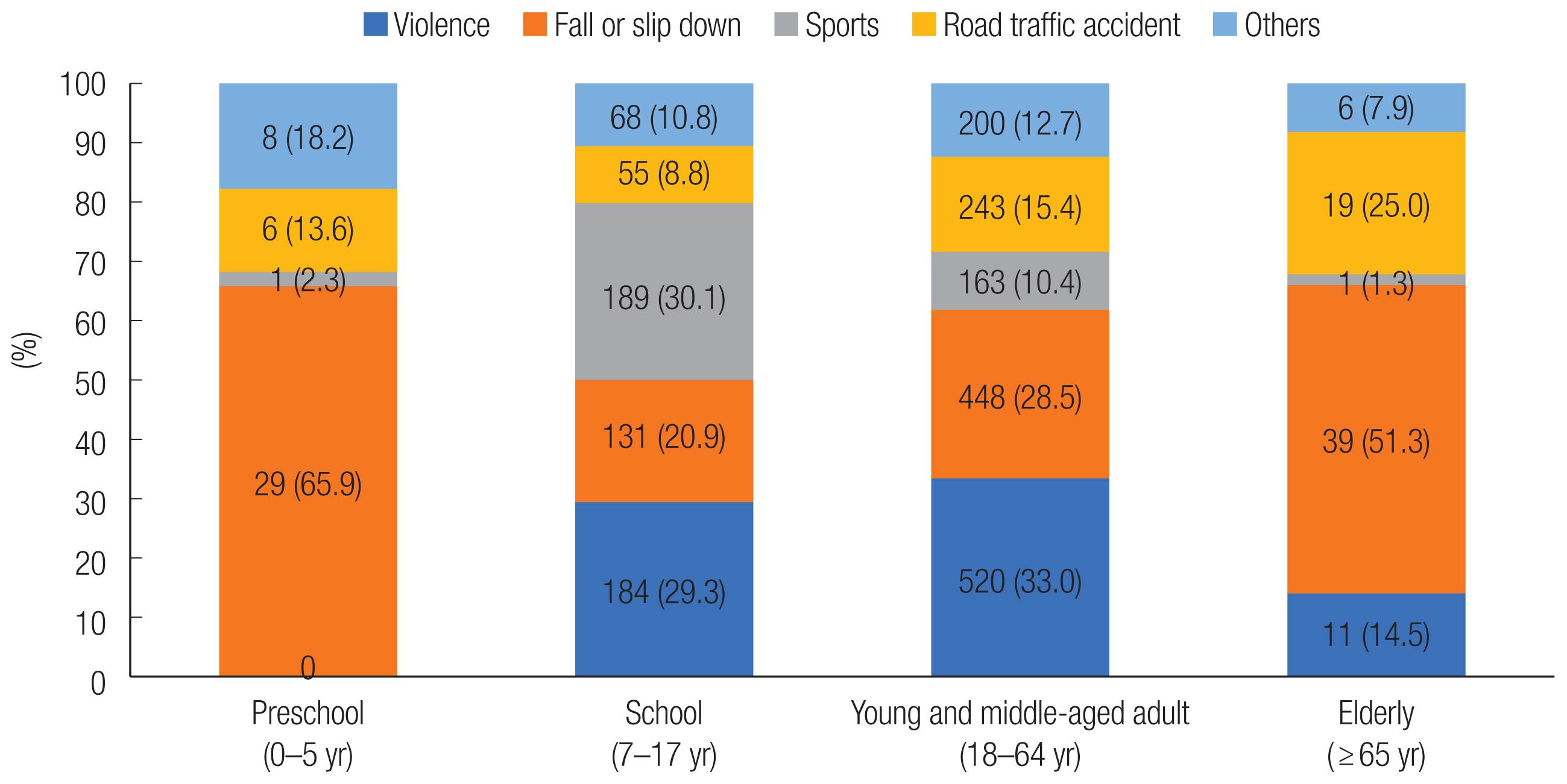

Seventy-six of the 2,321 nasal bone fracture patients (3.3%) were elderly (50 men [65.8%] and 26 women [34.2%]). Among the elderly nasal fracture patients, the most common cause of injury was falling or slipping down, with 39 patients (51.3%), followed by road TA with 19 patients (25.0%). The sex ratio also showed a significant difference from the under-65 group, which contained 1,755 male patients (78.2%) and 490 female patients (21.8%) (

p=0.011) (

Table 1). A particularly significant difference was found in the sex ratio between the elderly group and the school-age group (

p<0.001). Among patients under the age of 65, violence was the most common cause, accounting for 704 cases (31.4%), followed by falling or slipping down, which was the cause of injury in 608 patients (27.1%); this difference was statistically significant in comparison to the elderly (

p<0.001). Significant differences were also found in comparisons with the preschool group (

p=0.007), the school-age group (

p<0.001), and the young and middle-aged adult group (

p< 0.001) (

Table 1).

Fig. 1 shows a 100% stacked column chart of injury causes for each group.

In the analysis of injuries according to the Stranc and Robertson classification, the predominant fracture vector in the elderly was lateral force (n=49; 64.5%), whereas 27 patients (35.5%) had a frontal impact. The distribution of fracture planes was as follows: plane 2 with lateral force, 40 patients (52.7%); plane 2 with frontal impact, 18 patients (23.7%); and plane 3 with lateral force, eight patients (10.5%). No significant difference was found in the fracture vector and plane between the elderly patients and those under 65 years of age (

p=0.810 and

p=0.318, respectively). However, the elderly group showed a statistically significant difference from the preschool group in the fracture vector (

p<0.001) and from the preschool and school-age groups in the fracture plane (

p<0.001 and

p=0.039, respectively) (

Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Nasal bone fractures are very common because the nose protrudes from the middle of the face, making it vulnerable to impact and fracture even in relatively low-velocity collisions. Due to structural changes of the nasal bone with age, the elderly are particularly susceptible to fracture [

14]. Older adults are also relatively likely to experience severe fractures. According to Toriumi and Rosenberger [

15], aging causes bone resorption, especially in the middle third of the face, which manifests as enlargement of the superomedial and inferolateral orbital aperture width. Serifoglu et al. [

16] pointed out that this indicates an enlargement of the internasal angle with aging, which is associated with weakening and loss of nasal bone support.

In this paper, we investigated the epidemiology and patterns of nasal bone fractures among elderly patients in pairwise comparisons with other age groups in order to address the relative gap in the scientific literature pertaining to these fractures among older adults.

The proportion of women in the elderly group was higher than in other groups. A possible explanation for this might be that after men retire from work, their engagement in social activities decreases and the life patterns of men and women become similar [

17]. Analogous patterns were observed in the cause of injury. Violence, which was the most common cause of injury among patients under the age of 65, was the third-lowest cause in the elderly. Similarly, it is thought that the retirement-related decrease in social activities diminished the prevalence of violence as a cause of injury. The elderly patients showed particularly significant differences in the sex ratio and cause of injury in comparison with school-age children (

p<0.001), reflecting the higher level of sports activities and the resultant greater vulnerability to fractures among male school-age children [

18,

19]. Correspondingly, reduced exercise activity and changes in preferred sports activities might explain why sports accounted for fewer nose fractures among the elderly than among school-age children and young and middle-aged adults.

The proportion of patients with fall or slip-down injuries decreased with age from preschoolers to school-age children and young and middle-aged adults, but significantly increased in the elderly. This might be explained by aging-related changes in the nervous and musculoskeletal systems [

20].

The proportion of injuries due to road TA was significantly higher in the elderly than in other groups, which can also be ascribed to aging-related physical changes. The elderly have poorer knowledge of transportation, lower compliance with laws, and less risk readiness and risk sensitivity in dangerous traffic conditions [

21].

The top two causes of nasal fractures among elderly patients were falling or slipping down and road TA; these accounted for over three-fourths of nasal fractures, and the proportions of patients with these injuries were significantly higher than in other age groups. Therefore, it is important to expand the social safety net, with possible steps including education on individual safety awareness, the availability of and use of safety devices, and protection zones for the elderly.

The most common injury vector in elderly patients was lateral force, followed by frontal impact. The injury vector reflects both the circumstances of the injury itself and defense mechanisms, such as turning the head or covering it with oneŌĆÖs hands at the time of injury. The distribution of injury vectors was significantly different between the elderly patients and the preschool group (p<0.001), but no significant difference was found when compared with the other age groups. Thus, the defense mechanisms of elderly patients seem to be similar to those of the non-preschool age groups.

Plane 2 with lateral force was the most common fracture plane in the elderly, followed by plane 2 with frontal impact and plane 3 with lateral force. The distribution of fracture planes in the elderly was significantly different from that in the preschool group (

p<0.001) and the school-age group (

p=0.039), but not from that in young and middle-aged adults (

p=0.589). In elderly patients, plane 1 was less common and plane 3 was more common than in other groups, indicating greater fracture severity. This may result from reduced bone strength, increased bone fragility, and decreased bone flexibility due to micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue, low bone mineral density, and enlargement of the internasal angle with aging [

14ŌĆō

16,

22ŌĆō

24]. In addition, the higher frequency of road TA among elderly patients implies that they may have been disproportionately likely to be injured by relatively high-velocity forces, leading to greater fracture severity.

This paper addressed a gap in the literature by investigating the epidemiology and patterns of nasal bone fractures in the elderly (Ōēź65 years) through a comparative analysis with different age groups. Particularly notable findings include the more even sex ratio in elderly patients, as well as increased fracture severity, a lower proportion of injuries caused by violence and sports, and a higher proportion of injuries caused by falling or slipping down and road TA. In light of these distinct patterns among elderly patients, it is necessary to take steps to reduce the incidence and severity of fractures by strengthening individual safety factors and expanding the social safety net. Some possible measures include providing education on individual safety awareness, ensuring the availability and use of safety devices, and creating protection zones for the elderly.

The limitations of this paper include its single-center, retrospective design and the non-inclusion of patients who received conservative treatment. Furthermore, this study also included patients with a history of previous nasal bone fracture or augmentation rhinoplasty, as well as patients who concomitantly presented with other facial bone fractures. These limitations could be addressed through a prospective study analyzing patients with only nasal bone fractures, regardless of treatment modality, and including statistical results from other hospitals.