Sequencing of panfacial fracture surgery: a literature review and personal preference

Article information

Abstract

Background

Treating panfacial fractures (PFFs) can be extremely difficult even for experienced surgeons. Although several authors have attempted to systemize the surgical approach, performing surgery by applying a unidirectional sequence is much more difficult in practice. The purpose of this study was to review the literature on PFF surgery sequence and to understand how different surgical specialists–plastic reconstructive surgery (PRS) and oral maxillofacial surgery (OMS)–chose sequence and review PFFs fixation sequence in clinical cases.

Methods

The PubMed and Google Scholar databases were scoured for publications published up until May 2020. Data extracted from the studies using standard templates included fracture part, fixation sequence, originating specialist, and the countries. Bibliographic details like author and year of publication were also extracted. Also, we reviewed the data for PFFs patients in the Trauma Registry System of Dankook University Hospital from 2011 to 2021.

Results

In total, 240 articles were identified. This study comprised 22 studies after screening and full-text analysis. Sixteen studies (12 OMS specialists and 4 PRS specialists) used a “bottom-top” approach, whereas three studies (1 OMS specialist and 2 PRS specialists) used a “top-bottom” method. However, three studies (only OMS specialists) reported on both sequences. In our hospital, there were a total of 124 patients with PFF who were treated during 2011 to 2021; 64 (51.6%) were in upper-middle parts, 52 (41.9%) were in mid-lower parts, and eight (6.5%) were in three parts.

Conclusion

Bottom-top sequencing was mainly used in OMS specialists, and top-bottom sequencing was used at a similar rate by two specialists in literature review. In our experience, however, it was hard to consistently implement unidirectional sequence suggested by a literature review. We realigned the reliable and stable buttresses first with tailoring individually for each patient, rather than proceeding in the unidirectional sequence like bottom-top or top-bottom.

INTRODUCTION

Panfacial fractures (PFFs) involve all three areas of the face: the frontal bone, midface, and mandible. However, when two of these three areas are involved, the term “panfacial bone fracture” is used in practice or in articles. In this study fractures involving two or three facial areas were included. The management of PFFs can be extremely challenging, even for experienced surgeons, partly because in many cases, there are no stable structures available to re-establish bone continuity. PFFs repair requires a systematic approach with a thorough understanding of the sequence; however, it is often difficult to determine the ideal sequence for treating these complex fractures.

Several authors have attempted to systemize the approach for managing PFFs in a stepwise manner. Craniofacial surgeons begin reconstruction with the frontal bone and proceed to the midface, using the upper face as a template for the lower face [1]. This method is named the “top-bottom” sequence. However, oral maxillofacial surgeons believe that the top-bottom sequence is inadequate because it could result in malocclusion when applied on PFFs that involve two occlusal parts: the maxilla and mandible. As a result, the “bottom-top” sequence has been suggested. The bottom-top sequence focuses on the mandible, which is the strongest bone of the facial skeleton and provides a buttress that can be accurately related to the cranial vault through rigid internal fixation [2].

Some surgeons prefer the bottom-top approach, while others use the top-bottom method. There are still other arguments about “inside-out” versus “outside-in” methods. However, performing surgery by applying a unidirectional sequence to PFFs is much more difficult in practice because every patient has a different type and severity of fracture. PFF surgery is usually performed by plastic reconstructive surgery (PRS) or oral maxillofacial surgery (OMS) specialists, and two specialists mainly manage these cases, depending on the fracture area. Consequently, sequence selection may differ between two specialists.

In this study, a review of the current literature on sequence selection for PFFs was conducted to determine and compare how the sequence used was selected by two specialists. Another objective was to review PFFs fixation sequence in clinical cases.

METHODS

Protocol and registration

An article review was performed by searching the Google Scholar and PubMed databases ion May 2020. The keywords used were tabulated (panfacial fracture, timing of repair, sequencing, top-bottom, top-down, bottom-top, bottom-up, outside-in, and inside-out).

Eligibility criteria

The study types permitted for inclusion were randomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, and case series/reports. All studies on the sequencing pattern of PFF surgery published in English until May 2020 were included. The exclusion criteria were inability to access the publication’s full text, articles not available in English language, in vitro studies, cadaveric studies, studies on pediatric PFFs, studies on PFFs accompanied by panfacial burns, studies on vascular complications associated with PFFs, and studies where distraction devices were used in PFF treatment. Studies that met one or more of the above-mentioned exclusion criteria were excluded.

Data collection process and data extraction

Two reviewers (DHK, JHY) performed the initial article title search of all databases. Duplicate articles were excluded. The abstract of each article was then reviewed. Articles deemed relevant based on the abstract review underwent a review of the full text of the publication. Articles that were not clearly excluded based on abstract reviews also underwent a full-text review. After reviewing the full-text articles, publications deemed relevant were analyzed. A standard template for data extraction was designed for the fracture part, fixation sequence, originating specialist, and the countries of the included studies. Apart from these details, bibliographic information (author and year) were also extracted. The chi-square test was performed to compare the distribution of sequences between the two specialists. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Study selection

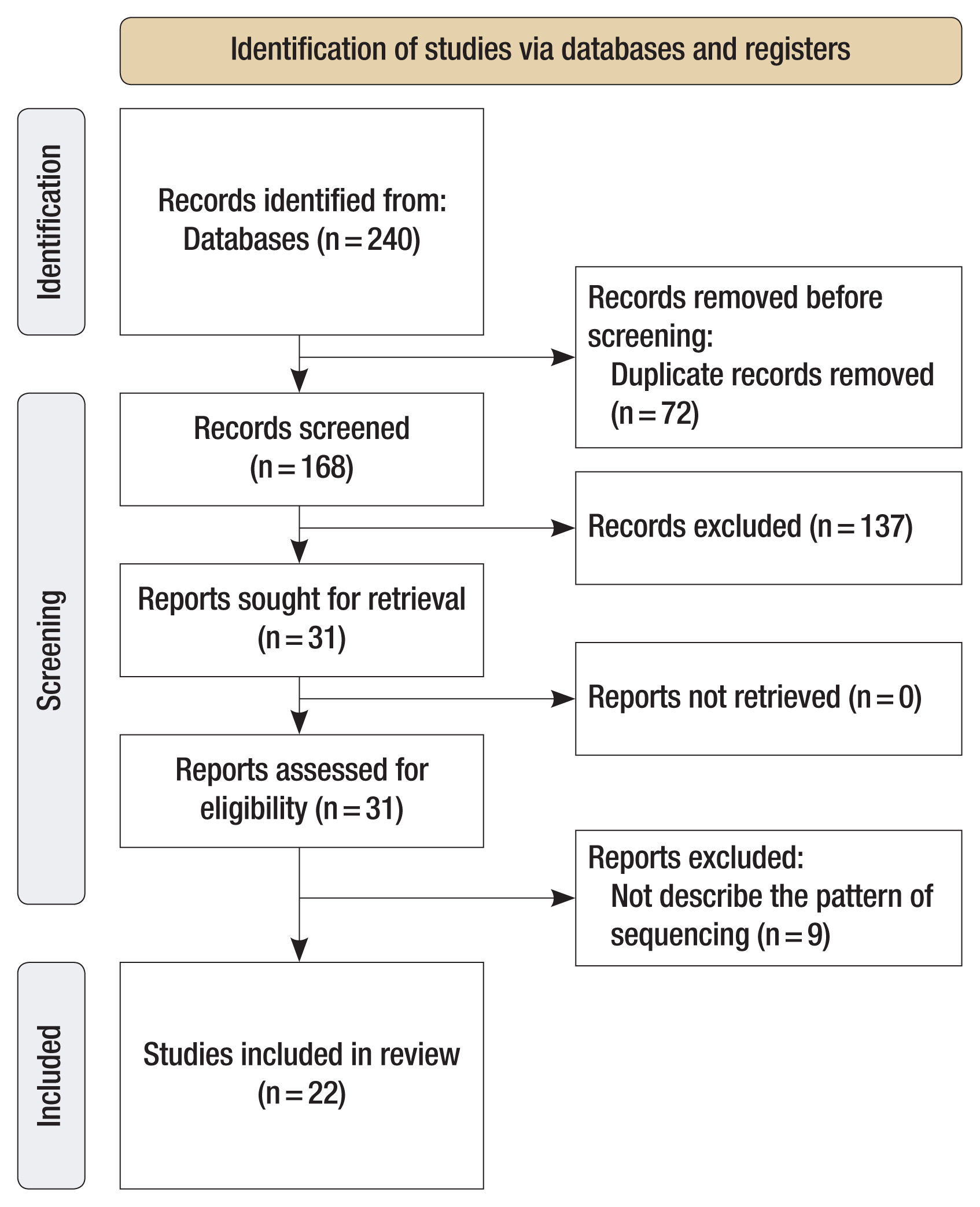

In total, 240 articles were identified. After removing duplicates, 168 articles remained. The titles and abstracts were read against the eligibility criteria, and 137 articles were excluded. The remaining 31 articles were screened. After full-text reading, nine articles were removed, as the studies did not describe the sequencing pattern. Ultimately, 22 articles were included in this review (Fig. 1). The included articles included 11 retrospective studies, two case series, and nine case reports (Table 1) [3–23].

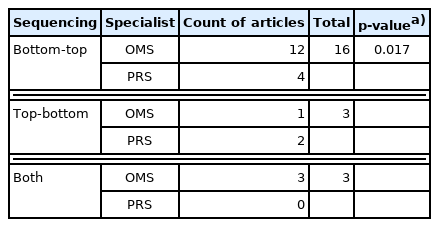

The sequences chosen by the two specialists are listed in Table 2. Sixteen studies (12 from OMS specialists and 4 from PRS specialists) used a bottom-top approach, whereas three studies (1 from an OMS specialist and 2 from PRS specialists) used a top-bottom method. However, three studies (only from the OMS specialist) reported on both sequences. Of the 16 studies published by OMS specialists, 12 used a bottom-top approach, the top-bottom approach was used in one study and both approaches were used in three studies. The distribution of sequences (bottom-top, top-bottom, and both) in the two groups was statistically different (p=0.017).

Clinical cases

As a regional trauma center, our institution has admitted and treated a significant number of patients with PFF. The fracture sites and number of staged surgeries performed on patients treated for PFFs during the past decade (from 2011 to 2021) are reported in Table 3. Of the 124 patients with PFF who were treated, 64 (51.6%) had fractures located in the upper-middle face, 52 (41.9%) in the mid-lower face, and eight (6.5%) had fractures in all three parts (upper-mid-lower face). Regarding the number of staged surgeries, 105 patients (84.7%) had one stage, 16 (12.9%) had two stages, two (1.6%) had three stages, and one (0.8%) had a four-stage surgery. All patients were treated by reduction and fixation on reliable buttresses.

Fracture areas and staged surgery of the patients treated for panfacial bone fractures during the past decade in our hospital

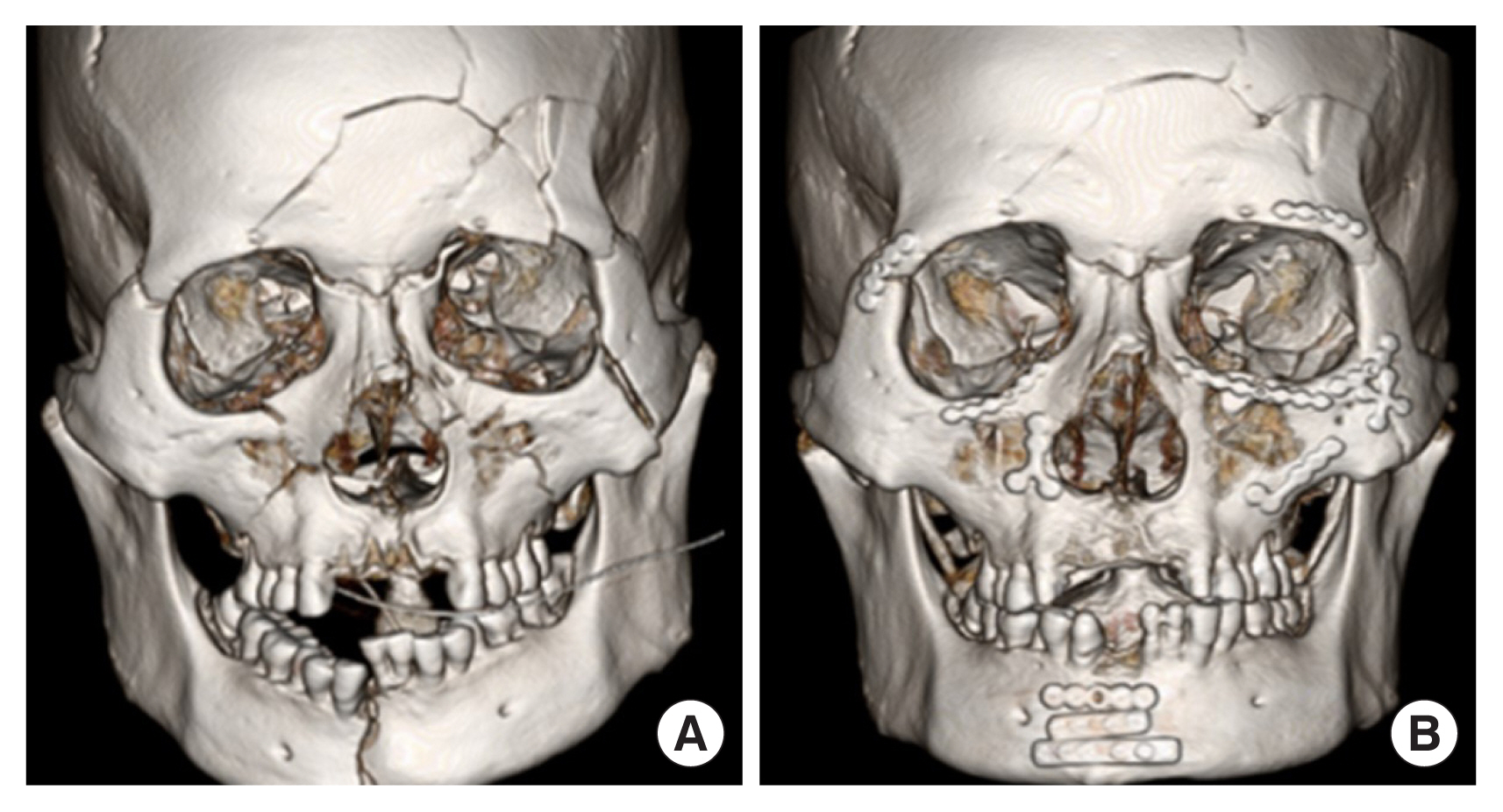

In the case of upper-middle PFFs, the top-bottom sequence is generally considered as preferable, but in our experience, we reduced the reliable buttresses and large bone fragments first rather than following the top-bottom sequence (Fig. 2). The bottom-top sequence is usually preferred for mid-lower PFFs; however, the buttresses and large bones of the midface are first reduced in cases of severe (displaced and multi-fragmentary) mandibular fractures (Fig. 3). Likewise, in PFFs involving all three parts (upper, middle, and lower) of the facial skeleton, reliable buttresses and large bone fragments were reduced first, rather than applying a unidirectional sequence (Fig. 4).

Upper-middle panfacial fracture case. (A) Preoperative (B) Postoperative computed tomography. Reliable buttress (left fronto-zygoma suture) was reduced first and then reduced clockwise. Finally, small bone fragment (in the right transverse frontal buttress) was reduced.

Mid-lower panfacial fracture case. (A) Preoperative (B) Postoperative computed tomography. Displaced and multi-fragmented mandible fracture existed in the left angle and ramus. Midface (reliable buttress and large bone fragment) was reduced first, and then lower face (unreliable buttress and small bone fragment) was reduced.

DISCUSSION

PFFs include fractures involving the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the face, including multiple fractures of the mandible, maxilla, zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC), frontal bones, and naso-orbito-ethmoid (NOE) regions. Historically, these fractures were treated conservatively, which led to significant posttraumatic problems, including crippling malocclusion, significant increase in facial width, and decreased facial projection [1]. Treatment of PFFs can be difficult because of the apparent loss of all references for facial skeleton reconstruction, particularly in fractures interrupting the maxillary and mandibular arches, which should constitute recognizable occlusion and bone continuity [24]. As with other multiple fractures, it is necessary to outline a detailed plan before surgery to determine the buttresses to be reduced and the sequence of reduction for successful surgical management of PFFs.

The literature review highlighted sixteen studies that reported the “bottom-top and outside-in” sequence. The mandible provides a foundation and firm framework for reconstructing the craniofacial skeleton because it is a long, solitary, and powerful bone in the face [6,10,15]. By selecting the mandible as the first point of fixation in the PFFs, the width, height, and projection of the lower face were determined through the body, condyle/ramus, and symphysis areas [8,11,16]. Additionally, the mandible maintains continuity between the lower third and the entire facial skeleton by connecting with the maxilla and occlude the skull base via the temporomandibular joint [5]. The midface was fixed using the outside-in principle after the bottom-top anatomic reduction [14]. Specifically, fixation of the midface begins in the ZMC region and ended in the NOE region. For reconstruction, the ZMC had more definitive landmarks than the NOE complex [7]. An additional benefit of ZMC fixation is that it allows control over the transverse and anteroposterior dimensions as well as stability of the lateral pillar [17]. In contrast to other studies, Pau et al. [12] used a bottom-top and inside-out sequence in their intracranial reduction procedure because of nasal bone dislocation into the anterior skull.

The top-bottom sequence was used and achieved good results in three studies. Kim et al. [18] used a top-bottom sequence and preferred the inside-out approach in rare cases involving frontal bone fractures near the nasofrontal junction. In cases with open wounds near the frontal bone fracture site, but no comminuted fracture in the NOE area, they began the reduction from the center of the frontal bone through laceration. Vasudev et al. [19] used the top-bottom technique and determined that this approach enables the proper restoration of both form and function. Because of their familiarity with midface reduction, Yun and Na [20] first applied arch bars and then reduced the frontal bone fracture, followed by midface and mandible fractures in this sequence. Three studies described both “top-bottom, inside-out” and “bottom-top, outside-in” sequences [21–23]: Degala et al. [21] compared the bottom-top, inside-out sequence with the top-bottom, outside-in sequence in the treatment of PFFs to evaluate the outcome of these approaches. Similar clinical outcomes were observed in the 11 cases in that study. The other two studies determined the sequence according to the case [22,23].

The surgical sequence favored by OMS surgeons who specialize in mandibular fractures may differ from that favored by PRS surgeons who are accustomed to operating on mid-facial fractures or by neurosurgeons who deal with skull fractures. These controversies are caused by the difference in the frequencies of certain fractures encountered in a particular field. The total number of patients reviewed in the 22 articles was 749, of which 370 were managed by OMS and 379 by PRS. Among these patients, 249 had clearly documented fracture sites in OMS and 112 in PRS. Furthermore, 234 of the 249 (94.0%) OMS-managed patients had fractures involving the lower face area, whereas only 45 of 112 (40.2%) PRS-managed patients had lower face fractures. This shows that the fracture types or locations generally encountered by each specialist may be different. Consequently, each specialist was compelled to assert a distinct sequence.

In actual clinical practice, most cases requiring surgery usually involve fractures of only two of the three parts (upper, middle, and lower) of the facial skeleton, rather than severe fractures of all three parts. This causes a dilemma regarding whether upper or lower fractures should be prioritized during surgical reduction. Based on this, PFFs can be broadly classified as mid-lower (maxillomandibular) or upper-middle (fronto-orbital, fronto-zygomatic, or fronto-maxilla) facial bone fractures. The use of this classification prevents confusion when deciding on a bottom-top or top-bottom surgery sequence. Maxillo-mandibular fractures occurring in the mid-lower facial bones centered on the occlusal surface should be reduced using the bottom-top sequence, as this first reduces the mandibular buttress, thereby restoring the occlusal surface. In contrast, PFFs that mainly involve the frontal bone and mid-facial bone, which is the upper-middle part of the facial bone, should be treated using the top-bottom sequence, which restores the transverse frontal buttress first.

However, in PFFs, a straightforward operation may not always be achieved, even when the above methods are considered. Therefore, a universal concept that can effectively deal with any PFFs is required. For example, when we combined multiple pieces of a puzzle, we did not put them in a unidirectional manner. The easiest way to put together a puzzle is to set the borders of the puzzle first, then place the most reliable pieces in that position, and then place the large pieces before placing the smaller pieces. Similarly, when aligning multiple facial bone fractures, it is best to first align the buttress that determines the width and height of the face; second, align a reliable fracture fragment to its original position; and third, align a thick, large, and stable bone fragment rather than a small bone fragment.

Bottom-top sequencing was mainly used in OMS specialists, and top-bottom sequencing was used at a similar rate by two specialists in literature review. In our experience, however, it was hard to consistently implement unidirectional sequence suggested by a literature review. We realigned the reliable and stable buttresses first with tailoring individually for each patient, rather than proceeding in the unidirectional sequence like bottom-top or top-bottom and achieved a good outcome.

Abbreviations

NOE

naso-orbito-ethmoid

OMS

oral maxillofacial surgery

PFF

panfacial fracture

PRS

plastic reconstructive surgery

ZMC

zygomaticomaxillary complex

Notes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dankook University Hospital (IRB No. 2022-10-004) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The informed consent was waived because this study design is a retrospective review.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Dong Hee Kang. Formal analysis: Dong Hee Kang. Methodology: Jae Hee Yoon, Dong Hee Kang. Writing - original draft: Jae Hee Yoon. Writing - review & editing: Dong Hee Kang. Investigation: Dong Hee Kang. Resources: Dong Hee Kang, Hyonsurk Kim. Supervision: Dong Hee Kang. Validation: Hyonsurk Kim.