|

|

- Search

| Arch Craniofac Surg > Volume 21(6); 2020 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

Full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs) have been widely used after facial skin cancer resection, for correcting defects that are too wide to be reconstructed using a local flap or if structural deformation is expected. The preauricular, posterior auricular, supraclavicular, conchal bowl, nasolabial fold, and upper eyelid skin areas are known as the main donor sites for facial FTSG. Herein, we aimed to describe the effectiveness of using infraclavicular skin as the donor site for specific cases.

Methods

We performed FTSG using the infraclavicular skin as the donor site in older Asian adults following skin cancer resection. Outcomes were observed for > 6 months postoperatively. The Manchester Scar Scale was used for an objective evaluation of satisfaction following surgery and scarring.

Results

We analyzed the data of 17 patients. During follow-up, the donor and recipient sites of all patients healed without complications. Upon evaluation, the average Manchester Scar Scale scores for the recipient and donor sites were 7.4 points and 5.7 points, respectively.

Conclusion

In general, conventional donor sites, such as the preauricular, posterior auricular, and supraclavicular sites, are widely used for facial FTSG because they achieve good cosmetic results. However, the infraclavicular skin may be a useful donor for facial FTSG in cases where the duration of time spent under anesthesia must be minimized due to a patient’s advanced age or underlying health conditions, or when the recipient site is relatively thick area, such as the nose, forehead, or cheek.

Full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs), a classic reconstruction method for facial skin defects, have been used for large defects or in areas where severe distortion is expected upon reconstruction with primary closure or for local flaps, such as the nasal area, periorbital area, and the ear [1]. Factors such as skin thickness, color, and texture, the pattern of sun exposure, and adnexal quality should be considered when selecting the appropriate donor site [1,2]. Considering these factors, preauricular, posterior auricular, supraclavicular, conchal bowl, nasolabial fold, and upper eyelid skin areas have been mainly used as donor sites for facial FTSG [1-4]. However, color mismatch from using non-facial skin as a donor, as well as the higher proneness of Asian skin to hypertrophic scarring and hyperpigmentation than that of Caucasian skin, are limitations when using supraclavicular and clavicular areas as donor sites [3,5]. We performed multiple FTSGs using infraclavicular skin as the donor on skin defects caused by skin cancer resection, and contrary to the aforementioned concerns, we obtained satisfactory results. Therefore, this work aimed to describe the advantages of infraclavicular skin as a donor site and the specific cases in which this donor site is useful.

This was a retrospective study of patients who had undergone facial skin cancer resection or reconstruction between March 2017 and June 2019. Patients who underwent facial skin cancer resection for melanoma, Bowen’s disease, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) were selected from medical records. We included patients who underwent FTSG using an infraclavicular donor site and excluded those who died during the study period. Patients who were followed up for >6 months were surveyed for satisfaction.

The requirement for patient informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles, and we obtained institutional review board approval (IRB No. JEJUNUH 2020-06-004).

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia. The excision line was designed to include a safety margin of >3 mm for BCC and >5 mm for SCC around the cancer lesion. The infraclavicular donor site was designed to be elliptically shaped (Fig. 1). Two operators simultaneously performed the cancer lesion resection and skin harvesting from the donor site. The pathologist processed the frozen biopsy to ensure that the excised lesion margin was clear (i.e., cancer was not involved). The residual adipose tissue was trimmed, and the graft was fixed on the recipient site. Simultaneously, primary closure of the donor site was performed. Absorbable suture using 5-0 PDS was applied on the subcutaneous tissue, while continuous suture using nylon 5-0 and simple interrupted suture were performed on the skin.

Tie-over and compressive dressings were applied on the recipient and donor sites, respectively (Fig. 2). The tie-over dressing was removed 1 week postoperatively, whereas the infraclavicular site was stitched out 2 weeks postoperatively.

Outcomes were observed for >6 months postoperatively. The Manchester Scar Scale was used for an objective evaluation of satisfaction following surgery and scarring; the scale score ranges from 5 to 18 points, where a lower score indicates lesser scarring [6]. The five parameters included in the evaluation were scar color, skin texture (matte or shiny), skin contour, the degree of distortion, and texture. Scarring in the recipient and donor sites was evaluated by a surgeon in an outpatient clinic, whereas a questionnaire on surgery satisfaction was administered over the phone when a hospital visit was not feasible.

We analyzed the data of 17 patients, four men and 13 women, who met the inclusion criteria. Patient age ranged from 67 to 95 years, with a mean age of 80 years. In terms of skin cancer types, there were eight cases of BCC, seven cases of SCC, one case of Bowen disease, and one case of melanoma. A similar proportion of BCC and SCC cases was observed, which comprised the majority of the cases. The number of cases based on the locations of cancer lesions were: five, four, four, three, and one cases with lesions on the nose, temple, glabella, cheek, and forehead, respectively. Four of the five cases on the nose and all cases on the glabella were classified as BCC, whereas three of the four cases on the temple and two of the three cases on the cheek were classified as SCC. Hence, there were mostly BCCs on the nose and glabella, and SCCs on the cheek and temples. The size of the cancer lesions ranged from 7 to 45 mm, with a mean diameter of 24 mm. Most lesions on the glabella and cheek with a diameter <25 mm were relatively smaller than those found on the cheek, forehead, and temples. The mean operation time was 78.7 minutes (Table 1).

The patients were observed for at least 6 months, and the donor and recipient sites of all patients healed without complications. Postoperative photographs of lesions on the nose and glabella are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. Upon evaluation, it was demonstrated that, the average Manchester Scar Scale scores for the recipient and donor sites were 7.4 points and 5.7 points, respectively. A more detailed analysis showed that mild depression in the contours of the recipient sites resulted in lower satisfaction (mean score=1.8), whereas hyperpigmentation resulted in lower satisfaction in the donor sites (mean score=1.6). However, overall, based on the scar scale satisfaction assessment, the patients felt comfortable and satisfied with the surgery (Table 2).

In general, using a local flap is the first method of choice for constructing a facial soft tissue defect following skin cancer resection because it achieves cosmetically excellent results. However, when the defect size is large or if structural deformation is expected, FTSG is considered [7]. When selecting a skin graft donor site, not only skin characteristics, such as skin thickness, color, adnexal quality, and texture, but also a variety of other factors, such as surgical feasibility, scarring of the donor site, and patient satisfaction, should be considered. Considering these factors, the preauricular, posterior auricular, nasolabial fold, and upper eyelid skin areas are used for facial FTSG because they are well known donor sites for achieving good cosmetic results [1-4]. The commonly used posterior auricular grafts are advantageous as they can cover the scar; however, they are limited in terms of the surface area that can be used [8]. Supraclavicular grafts have the advantage of having a relatively large usable surface area than postauricular area. However, the posterior auricular skin and supraclavicular skin are both considerably thin at approximately 0.71 and 0.77 mm, respectively, which may cause depression when implanted on areas, such as the forehead, nose, and cheek, which are relatively thicker (>1 mm) [2,9,10].

The infraclavicular skin used in this study has the following advantages. First, a larger amount of skin can be harvested from this area than from the facial or supraclavicular donor sites. There is no physiological barrier when designing the area to be harvested, and there is less anatomical distortion, even with primary closure. Although split-thickness skin grafts can be used in large facial reconstruction, the poor texture and marked contracture of these grafts often result in permanent cosmetic or functional impairments. A large graft with a maximum size of 15×5 cm can be also harvested bilaterally from the supraclavicular area depending on age and skin laxity [11]. However, disadvantages, such as bony prominence, can cause scar widening wound breakdown, and the scar may be exposed when wearing clothes wherein the clavicle is visible [12]. In fact, patients who complained of scarring at the supraclavicular donor site have also been reported [13]. The infraclavicular area has the important advantage of remaining covered, even when wearing clothes with a revealing neckline. Additionally, although there were concerns regarding the formation of a hypertrophic scar in the chest area, our findings showed that the contours of the formed scars were mostly flat. In our study, the patients’ mean age was 80 years, so the infraclavicular area is loose enough for harvesting a large graft. An area of up to 5×12 cm in size could be harvested, and primary closure was successfully performed. A previous study reported that the lateral thoracic area can be a useful donor site of FTSG for reconstructing a large facial skin defect and has advantages in terms of color, texture, thickness, and convenience [12,14].

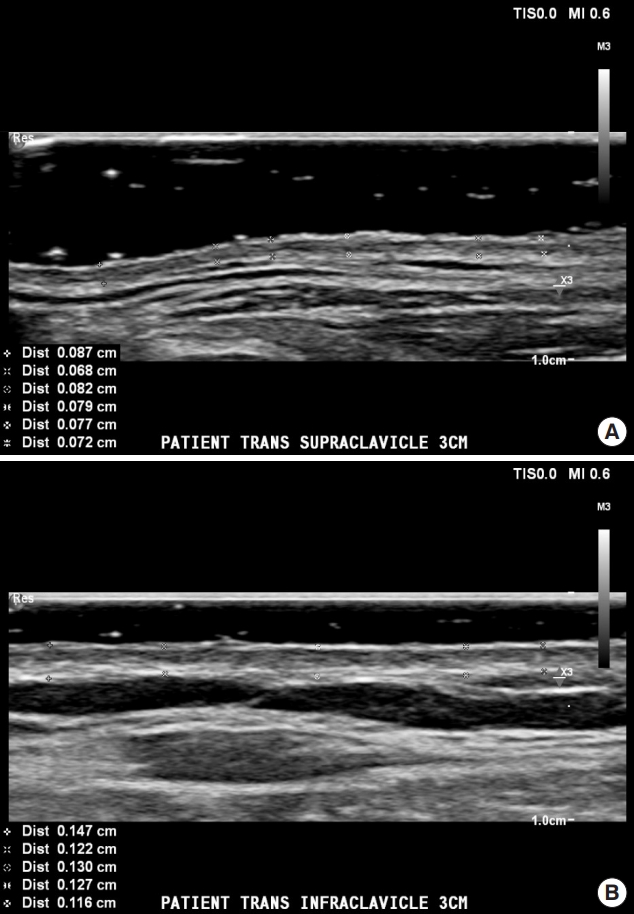

Second, minimal depression can be achieved when reconstructing thicker skin, such as on the forehead, nose, and cheek. A previous study result reported that a contour problem occurred when using the periauricular and supraclavicular skin for reconstructing thick skin, such as on the lower third of the nose [15]. In this study, many cases of skin cancer lesions with thickness >1 mm on the forehead, nose, and cheek were operated on (Table 1). Considering that skin thickness in the upper chest was approximately 1.44 mm, thicker skin can be obtained from this area compared to that from the postauricular (0.71 mm) or the supraclavicle donor sites (0.77 mm) [9,10]. In this study, ultrasonography was used to measure skin thickness in three patients, where infraclavicular skin was approximately >0.5 mm thicker than in the supraclavicle area (Fig. 5). The failure rate of a thick graft is higher than that of a thin graft because it entails a high metabolic rate. However, during >6 months of follow-up, graft uptake was successful in all patients. Depression at the recipient site was rare, even when contracture of the graft was considered.

Third, the duration of the procedure can be minimized. The mean age of skin cancer patients in Korea is over 60 years, similarly, the subjects in this study had a mean age of 80 years [16]. In such cases, minimizing the duration of surgery is crucial to reduce postoperative complications. Because there is enough space between the donor and the recipient site, cancer excision and skin harvest can be performed simultaneously by a twoteam approach. Furthermore, compared with areas, such as the posterior auricular skin, which tend to be less accessible or indented, the infraclavicular skin area provides the advantage of allowing patients to change the dressing themselves.

A color mismatch may occur compared with facial donor sites. Although the scar scale of the recipient site demonstrated color parameter with relatively lower satisfaction than other parameters, minimal color difference was observed than anticipated in the postoperative evaluation, and patient satisfaction levels were high (Figs. 3, 4).

Some limitations of this study are the relatively small number of subjects and the lack of a control group, which posed a challenge in directly comparing with other donor sites. There is also a practical limitation because directly comparing the operation time and operation results in the same patient is difficult. Therefore, the infraclavicular donor site data presented in this paper needs to be further validated to be generalized. The efficacy of infraclavicular skin as a donor for facial skin grafts can be confirmed by direct comparison with other donor sites, and long-term research with larger study population is required.

Local flap surgery is a common method of reconstructing a defect after resection of the skin cancer if the defect is small and structure distortion is not expected [17,18]. The use of the facial skin as donor sites can be cosmetically superior even when skin graft is required for a large defect. However, the present study indicates that the infraclavicular skin area may be a useful donor site for facial FTSG in cases where the defect size is large or when thick areas, such as the nose, forehead, or cheek, have to be reconstructed and when the duration of time spent under anesthesia needs to be minimized due to the patient’s old age or underlying health conditions.

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the 2020 education, research, and student guidance grant funded by Jeju National University.

Fig. 1.

Donor sites for full-thickness skin grafting on the face. Supraclavicular, clavicular, and infraclavicular areas.

Fig. 2.

Immediate postoperative photograph of a 67-year-old man with melanoma on the left malar area.

Fig. 3.

Postoperative photographs of a 74-year-old man with basal cell carcinoma on the glabella. (A) Recipient site. (B) Donor site. Asterisk indicates donor site scar.

Fig. 4.

Postoperative photographs of a 78-year-old woman with basal cell carcinoma on the nose. (A) Recipient site. (B) Donor site. Asterisk indicates donor site scar.

Fig. 5.

Ultrasonography of the (A) supraclavicle skin and (B) infraclavicular skin is approximately >0.5 mm thicker than in the supraclavicle skin.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

REFERENCES

1. Johnson TM, Ratner D, Nelson BR. Soft tissue reconstruction with skin grafting. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;27(2 Pt 1):151-65.

2. Dimitropoulos V, Bichakjian CK, Johnson TM. Forehead donor site full-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:324-6.

3. Rathore DS, Chickadasarahilli S, Crossman R, Mehta P, Ahluwalia HS. Full thickness skin grafts in periocular reconstructions: long-term outcomes. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;30:517-20.

4. Matheson BK, Mellette JR Jr. Surgical pearl: clavicular grafts are “superior” to supraclavicular grafts. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37:991-3.

5. Kim S, Choi TH, Liu W, Ogawa R, Suh JS, Mustoe TA. Update on scar management: guidelines for treating Asian patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;132:1580-9.

6. Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, Levinson H. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty 2010;10:e43.

7. Park YJ, Kwon GH, Kim JO, Ryu WS, Lee KS. Reconstruction of nasal ala and tip following skin cancer resection. Arch Craniofac Surg 2019;20:382-7.

8. Lau B, Younger RAL. Skin grafts in head and neck reconstruction. Oper Tech Otolayngol Head Neck Surg 2011;22:24-9.

10. Ha RY, Nojima K, Adams WP Jr, Brown SA. Analysis of facial skin thickness: defining the relative thickness index. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;115:1769-73.

12. Yoo WJ, Lim SY, Pyon JK, Mun GH, Bang SI, Oh KS. Usefulness of full-thickness skin graft from anterolateral chest wall in the reconstruction of facial defects. J Korean Soc Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;37:589-94.

13. Custer PL, Harvey H. The arm as a skin graft donor site in eyelid reconstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;17:427-30.

14. Celikoz B, Deveci M, Duman H, Nsanci M. Recontruction of facial defects and burn scars using large size freehand fullthickness skin graft from lateral thoracic region. Burns 2001;27:174-8.

15. McCluskey PD, Constantine FC, Thornton JF. Lower third nasal reconstruction: when is skin grafting an appropriate option? Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;124:826-35.

16. Oh CM, Cho H, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Roh YH, Jeong KH, et al. Nationwide trends in the incidence of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers from 1999 to 2014 in South Korea. Cancer Res Treat 2018;50:729-37.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 7 Crossref

- Scopus

- 4,557 View

- 131 Download

- Related articles in ACFS