|

|

- Search

| Arch Craniofac Surg > Volume 22(4); 2021 > Article |

|

This article has been corrected. See "Corrigendum to ŌĆ£A hemangioma in the masseter muscle: a case reportŌĆØ" in Volume 22 on page 285.

Abstract

Intramuscular hemangiomas of the masseter muscle are uncommon tumors and therefore can be difficult to accurately diagnose preoperatively, due to the unfamiliar presentation and deep location in the lateral face. A case of intramuscular hemangioma of the masseter muscle in a 66-year-old woman is presented. Doppler ultrasonography showed a 34├Ś 15 mm hypoechoic and hypervascular soft tissue mass in the left masseter muscle, suggesting hemangioma. The mass was excised via a lateral cervical incision near the posterior border of the mandibular ramus. The surgical wound healed well without complications.

Intramuscular hemangiomas (IMHs) constitute less than 1% of all hemangiomas [1], and are usually located in the skeletal muscles of the trunk or limbs. However, 13.8% of IMHs are located in the head and neck region, where the masseter muscle is the most common site [2]. Due to the rarity of these tumors, their deep intramuscular location and the presence of the overlying parotid gland, accurate preoperative diagnosis occurs in less than 8% of cases [3].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown superiority in the exquisite delineation and contrast of the lesion from its surrounding tissue [4]. Computed tomography (CT) following injection of the contrast agent iopamidol is also helpful in diagnosing IMHs. A major disadvantage of the CT scan is that it is unable to clearly differentiate between the anatomic extent of the IMHs and the muscle [5]. Ultrasonography is able to differentiate between muscle, vascular tissues and surrounding tissues. Color Doppler can differentiate between arterial, venous, and lymphatic lesions. Both modalities are economical, rapid and free of radiation. They can be used as adjunctive tools for a preoperative diagnosis and are best used for follow-up studies [6].

In the present case, the diagnosis of IMH was made with Doppler ultrasonography.

Surgical removal of IMHs of the masseter muscle has commonly been done through a preauricular incision [4], but transcervical approach is also a convenient way to expose the masseter muscle without causing injury to the facial nerve. A collar incision in the submandibular region has been used for the transcervical approach. The authors modified the location of the collar incision from the submandibular region, to the lateral cervical region near the lateral mandibular border and called it a lateral cervical incision. The incision started at the inferior portion of the earlobe and proceeded to within 1 cm of the posterior border of the mandibular ramus, with a slight anterior curve at the mandibular angle.

A 66-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with a 2-year history of painless swelling in her left cheek during mastication. The patient recalled no clear history of trauma to that region. The swelling was soft and unnoticeable in the resting state but became a round, smooth, protruding mass with a diameter of 3 cm when the patient clenched her teeth (Fig. 1). The mass was slightly compressible and movable on the anterior surface of the lateral mandibular body. No pulsation or bruits was noted. Ultrasonography showed a hypoechoic intramuscular mass with tubular extension and internal hypervascularity on Doppler study (Fig. 2). IMH of the masseter muscle was suggested.

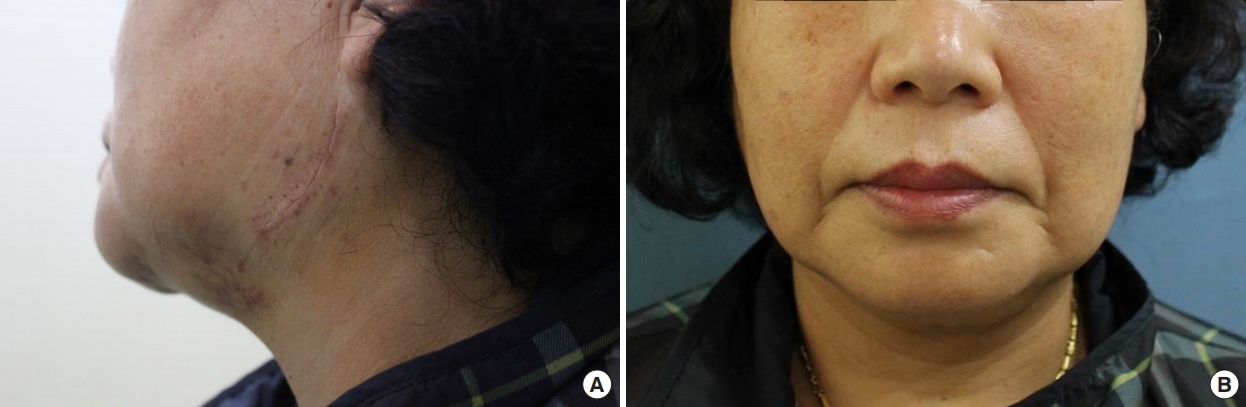

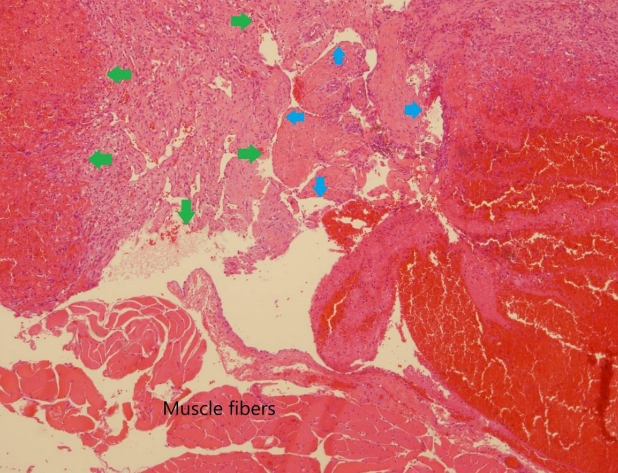

Under a provisional diagnosis of masseteric IMH, an incision line was drawn on the left lateral neck about 10mm from the posterior border of the mandibular ramus. After sedation and local anesthesia (0.5% lidocaine and 1:200,000 epinephrine), an incision of less than 5 cm in length was made on the design from the inferior part of the earlobe to the mandibular angle; the incision was slightly curved anteriorly to follow the mandibular angle. Taking care not to disrupt the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve, the anterior skin flap was deeply undermined to expose the platysma muscle. The platysma muscle was cut along the mandibular border and the fibrous capsule of the mass was exposed on the anterior surface of the ramus. The fibrous capsule was separated from the covering tissue to isolate the mass from the muscle. During the separation procedure, a short incision was made on the capsule, which revealed a bulging of dark purple, soft tissue, but no bleeding from the mass. The extruded tissue was not pure hemangioma but looked like an unusual mixture of hematoma and multiple small fibers. The extruded mass with its fibrous capsule was completely removed from the muscle tissue after the pedicle was ligated. The soft mass was about 15 mm in diameter (Fig. 3). After saline irrigation of the wound, the cut ends of the soft tissue were resutured to cover the masseter muscle and the incisional wound was closed by layers without a drain. The postoperative course was uneventful, without surgical complications such as infection or facial palsy. There was no swelling when the patient clenched her teeth and the cosmetic results were excellent (Fig. 4). Histological examination showed mixed vesseltype IMH (Fig. 5).

Accurate preoperative diagnosis of IMHs is very difficult due to the rarity of these tumors, which account for only 0.8% of all benign vascular tumors [1,7], and a lack of awareness of the characteristic clinical and radiological presentations. A proper radiological evaluation is required before choosing the surgical approach, and complete resection is the treatment of choice [8]. MRI is the most helpful and accurate tool for the diagnosis of IMHs that show low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images [4]. Plain X-ray and fine needle aspiration cytology may not be sufficiently specific for diagnostic purposes [4]. CT with injection of contrast agent is also helpful for diagnosis of IMHs [5]. Ultrasonography is the first-line approach to assess soft tissue masses [9] and can be used to differentiate between muscular and vascular structures, and Doppler ultrasonography is useful to demonstrate the presence of vascular structures in and around muscles and to evaluate pathological changes like fibrosis and calcification [10]. Angiography is not indicated unless there is a high suspicion of large vascular connections to the tumor with pulsation, bruits and thrills [11].

There is some confusion regarding the use of terms ŌĆ£hemangiomaŌĆØ and ŌĆ£vascular malformation.ŌĆØ Mulliken and Glowacki [12] classified vascular lesions into hemangiomas and vascular malformations. Hemangiomas were defined as present at birth as small red marks with a biphasic growth phase consisting of proliferation and spontaneous involution. Vascular malformations were usually noted at birth, grew proportionately with the child, did not regress, and consisted of capillary, venous, arterial and lymphatic vascular elements.

Allen and Enzinger [13] subdivided hemangiomas into three groups; small-vessels, large-vessels and mixed group with large and small vessels. Vessels with a diameter less than 140 ╬╝m were regarded as small vessels while those with a diameter greater than 140 ╬╝m were classified as large vessels. In practice, the small-vessel structure would be regarded as capillary hemangiomas, while the large-vessel group might be called cavernous or venous hemangioma.

The treatment of choice for IMHs of the masseter muscle is surgical excision of the lesion. This is preferred over other treatment modalities such as cryotherapy, steroid and sclerosing agent injection, embolization, and radiation therapy [2]. Local recurrence after surgical excision occurs in approximately 18% of cases due to incomplete excision [2]. The surgical approach for IMHs of the masseter muscle should allow wide exposure of the tumor with preservation of the facial nerve and normal regional structures. The preauricular approach may be necessary for complete excision, with superficial parotidectomy to expose IMHs of the masseteric muscle [4]. In the intraoral approach, a fine tube is inserted into StensenŌĆÖs duct for positional marking and a mucosal incision is created anterior to StensenŌĆÖs duct to approach the tumor [5]. The main advantages of the intraoral approach are easy approach to the tumor and an invisible postoperative scar. The disadvantages are that this approach is less likely to provide adequate exposure for optimal tumor resection and identification of adjacent nerves [2].

In the case described here, the lateral cervical incision within 1 cm of the posterior border of the mandibular ramus is a convenient way to expose the masseter muscle without causing injury to the facial nerve. It leaves a scar on the area that is not easily visible and is associated with a shorter operative time and better preservation of the facial nerves and parotid gland.

In conclusion, Doppler ultrasonography is a preferred initial imaging modality for superficial masses because of its low cost, general availability and high resolution. This study provides a useful reference for the diagnosis of IMH of the masseter muscle. Doppler ultrasonography is also the best choice for followup imaging of vascular tumor sites. A lateral cervical incision near the lateral mandibular margin provides a simple and easy approach that can clearly expose an IMH of the masseter muscle without causing injury to the facial nerves.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dongkang Medical Center (IRB No. ļÅÖĻ░Ģ 2021-05-03) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained.

Fig.┬Ā1.

A 66-year-old woman with an intramuscular hemangioma of the masseter muscle. A round protruding mass with a diameter of 3 cm appeared on the lateral cheek when the patient clenched her teeth. The lower marking indicates the mandibular border.

Fig.┬Ā2.

Doppler ultrasound showing a hypoechoic intramuscular mass with tubular extension (blue arrows) and internal hypervascularity.

Fig.┬Ā3.

Intraoperative photograph. A lateral cervical incision was made about 10 mm from the posterior border of the mandibular ramus and the platysma muscle was cut along the mandibular border to expose the fibrous capsule of the mass. Dark purple, soft tissue was pulled out through the incision on the capsule of the mass.

REFERENCES

1. Barnes L. Tumors and tumor like lesions of the soft tissue. In: Barnes L, editors. Pathology of the head and neck. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2001. p. 900.

2. Wolf GT, Daniel F, Krause CJ, Kaufman RS. Intramuscular hemangioma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 1985;95:210-3.

3. Avci G, Yim S, Misirliogolu A, Akoz T, Kartal LK. Intramasseteric hemangioma. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;109:1748-50.

4. Narayanan CD, Prakash P, Dhanasekaran CK. Intramuscular hemangioma of the masseter muscle: a case report. Cases J 2009;2:7459.

5. Cheng YT, Lai CC. Transcervical excision of intramasseteric cavernous hemangioma: a case report. Oncol Lett 2016;11:1657-60.

6. Rahmani G, McCarthy P, Bergin D. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for soft tissue lipomas: a systematic review. Acta Radiol Open 2017;6:2058460117716704.

7. Park H, Kim JS, Park H, Kim JY, Huh S, Lee JM, et al. Venous malformations of the head and neck: a retrospective review of 82 cases. Arch Plast Surg 2019;46:23-33.

8. Wee SJ, Park MC, Chung CM, Tak SW. Intramuscular hemangioma in the zygomaticus minor muscle: a case report and literature review. Arch Craniofac Surg 2021;22:115-8.

9. Kim JH, Ahn CH, Kim KH, Oh SH. Multifocal intraosseous calvarial hemangioma misdiagnosed as subgaleal lipoma. Arch Craniofac Surg 2019;20:181-5.

10. Lee JJW, Cho WS, Kim SB, Lee DH. Intramuscular cavernous hemangioma of the masseter muscle in child and adolescent. Korean J Head Neck Oncol 2015;31:27-30.

11. Odabasi AO, Metin KK, Mutlu C, Basak S, Erpek G. Intramuscular hemangioma of the masseter muscle. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1999;256:366-9.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 3 Crossref

- Scopus

- 3,923 View

- 95 Download

- Related articles in ACFS

-

Pyogenic granuloma of the hard palate leading to alveolar cleft: a case report2024 June;25(3)

Intramuscular epidermal cyst in the masticator space: a case report2023 August;24(4)

Solitary fibrofolliculoma on the nasal septum: a case report2023 June;24(3)

Periorbital cutaneous angiomyolipoma: a case report2023 April;24(2)